With nearly all the state’s students at home to prevent the spread of the coronavirus and Gov. Gavin Newsom’s prediction that they won’t be back in classrooms this school year, California’s top education leaders have vowed to keep up instruction.

But teachers and administrators tasked with delivering on that pledge are bumping up against logistical hurdles, murky guidance and uneven resources.

In a letter released Monday, the leaders of the state’s two largest districts — Los Angeles Unified and San Diego Unified — appealed to state lawmakers for guidance and financial support.

“Our schools serve a high portion of students from families living in poverty and their families cannot provide them with digital tools and internet access like more affluent school districts,” the superintendents wrote, appealing to the state for an emergency appropriation of at least $500 per student to cover the costs of making online distance learning more accessible.

The superintendents warned they are currently dipping into district reserves to cover costs. “Said simply, our budgets will not balance for the current fiscal year because of the extraordinary costs associated with responding to the global pandemic.”

They also asked state officials to amend graduation requirements, consider the implications of closure on students’ college prospects and create a coordinated statewide team to unite state and local efforts.

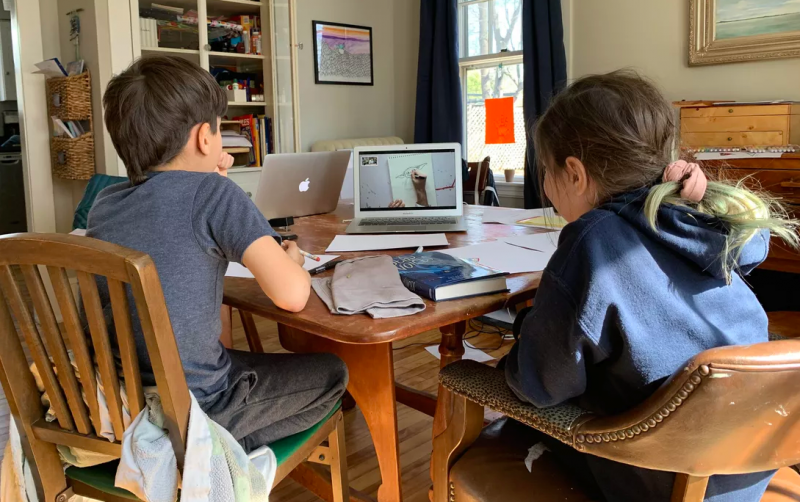

So far, interviews with educators suggest the experiences of the state’s 6.2 million students post-closure vary widely, and the inequities that existed in the classroom may only be exacerbated under the current circumstances.

Vanasit’s experiment, however chaotic, is in some ways a best-case scenario. She and her students have experience working with tech tools in class, plus her kids each have district-issued Chromebooks, which they were allowed to take home. Nearly all of her students also have internet access, and caregivers who can help them navigate the logistics of distance learning.

But in many other districts, not all kids have school-issued laptops, and even some of those who do haven’t been able to take them home. Oakland Unified School District, for instance, was preparing to distribute Chromebooks to students when a shelter-in-place order from the Alameda County Public Health Department temporarily thwarted the effort.

Still, Stephanie Ullman, who teaches sixth grade in Oakland, has found ways to reach students who have access to smartphones. She recorded herself reading texts and had students submit video responses through one familiar app and a written response through another.

“I can’t imagine doing it if your kids aren’t accustomed to the tech,” she says. “If your kids are unaccustomed or you aren’t accustomed it’s super difficult.”

In some districts, though, neither devices nor internet itself are broadly available to students. “Our families don’t have access to things that others may,” says Ashley Jones, a fifth grade teacher in the Twin Rivers Unified School District, outside Sacramento. “That’s the part where we’re a little bit lost, because we don’t have like a few kids that need this stuff; it’s like hundreds of them.”

School leaders around the state are scrambling to equalize resources. West Contra Costa Unified briefly reopened schools to allow families to pick up Chromebooks, chargers, books and work packets, and also plans to make Wi-Fi hotspots available. In Marysville Joint Unified School District, outside Yuba City, schools have boosted their Wi-Fi signals so families can park outside and access internet-based learning tools.

Los Angeles Unified is promising to put $100 million toward devices and internet access, and train teachers and families in online tools. The district announced Monday it had reached a deal with Verizon to ensure all students get an internet connection.