The evidence notwithstanding, many of America’s strongest environmental protections have long been under attack, and took a particularly harsh beating over the past four years of the Trump administration, when efforts to dismantle regulations went into extreme overdrive — much of which President Biden is now trying to undo.

For what it’s worth, though, the environmental outlook in the late 1960s wasn’t too rosy either.

After decades of largely unregulated industrial and economic growth in the wake of World War II, the U.S. had managed to majorly muck up its air and water resources. Toxic effluent from factories frequently spilled into streams and rivers. Open spaces were used as dumping grounds. DDT and other synthetic chemicals contaminated natural habitats and water supplies. And air pollution from factories and belching cars left many industrial areas shrouded in thick blankets of smog.

Here’s a handful of the environmental catastrophes that happened within less than three years:

- November 1966: In New York City, 168 people die of respiratory-related illnesses over a three-day period due primarily to horrendously poor air quality.

- March 1967: Interior Department Secretary Stewart L. Udall announces the first official list of endangered wildlife species. Among the 78 species is the bald eagle, America’s national bird.

- January 1969: A blowout at an offshore oil rig near Santa Barbara caused as much as 4.2 million gallons of crude oil to spill into the Santa Barbara Channel and onto nearby beaches. It lasts for 10 straight days, becoming (at that point) the largest oil spill in American history. Today, it ranks only third, overtaken by the 1989 Exxon Valdez and 2010 Deepwater Horizon spills).

- June 1969: A particularly fetid industrial stretch of the Cuyahoga River running through Cleveland bursts into flames (seriously) when oil-soaked debris in the water is ignited by sparks from a passing train.

A movement begins

As urban unrest and the anti-war movement ignited across the nation, environmental activism had yet to gain a strong foothold.

“If the people really understood that in the lifetime of their children, they’re going to have destroyed the quality of the air and the water all over the world and perhaps made the globe unlivable in a half century, they’d do something about it. But this is not well understood.”

That’s a quote from Sen. Gaylord Nelson, a Democrat from Wisconsin, who spearheaded a national day of awareness in the aftermath of these environmental disasters.

“If we could tap into the environmental concerns of the general public and infuse the student anti-war energy into the environmental cause, we could generate a demonstration that would force the issue onto the national political agenda.”

In late 1969, Nelson formed a bipartisan congressional steering committee and enlisted Denis Hayes, a 25-year-old Harvard Law School dropout, to coordinate the initiative. Influenced by anti-war campus activism, Hayes sought to organize environmental teach-ins throughout the country to occur simultaneously on April 22, 1970.

With a limited budget and no email or internet access, Hayes and a small group of organizers mailed out thousands of appeals, recruiting an army of young volunteers to organize local events in communities and campuses across the country.

On Nov. 30, 1969, the New York Times reported:

“Rising concern about the ‘environmental crisis’ is sweeping the nation’s campuses with an intensity that may be on its way to eclipsing student discontent over the war in Vietnam.”

The big launch

Interviewed in the recent PBS documentary “Earth Days,” Hayes recalled the sentiment:

“Lord knows what we thought we were doing. It was wild and exciting and out of control and the sort of thing that lets you know you’ve really got something big happening … What we were trying to do was create a brand-new public consciousness that would cause the rules of the game to change.”

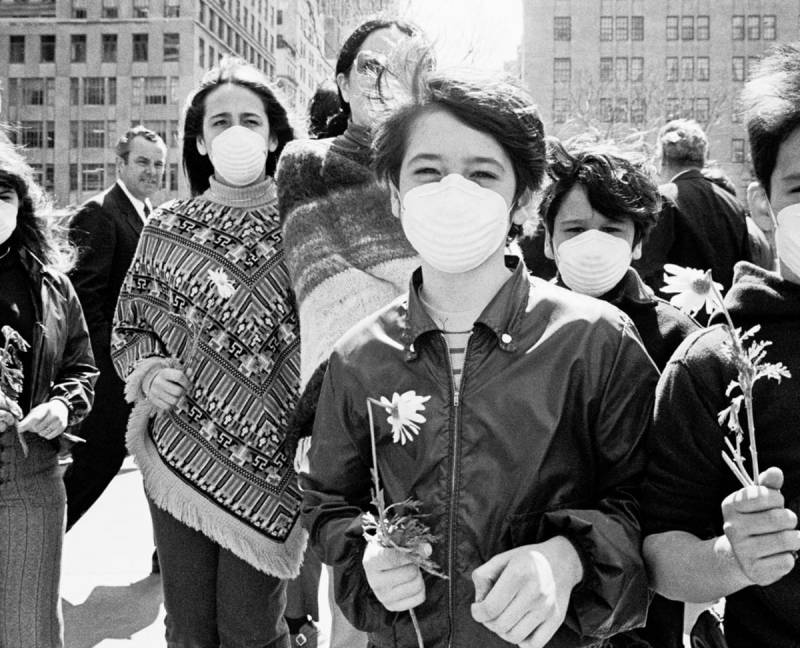

In the end, an estimated 20 million people participated in that first Earth Day, a name coined by advertising guru Julian Koenig (father of Sarah Koenig of “Serial” podcast fame).

Read the New York Times article from April 22, 1970.

“It was a huge high adrenaline effort that in the end genuinely changed things,” Hayes said. “Before [that], there were people that opposed freeways, people that opposed clear-cutting, or people worried about pesticides, [but] they didn’t think of themselves as having anything in common. After Earth Day they were all part of an environmental movement.”

Hayes’ assertions were affirmed by several national polls showing a rapid rise in the public’s concern about air and water resources. In the Gallup Opinion Index, the percentage of respondents who considered air and water pollution a top national problem rose from 17% in 1969 to 53% by 1970.

On Earth Day the following year, an independent group launched an anti-litter public service announcement, known as the “Crying Indian,” which featured a white actor in a headdress, rowing a birch bark canoe and shedding a tear when he sees garbage strewn everywhere. Despite the ad’s culturally questionable premise, it proved enormously popular and is still considered one of the most successful public service announcements in history.

Unexpected alliances

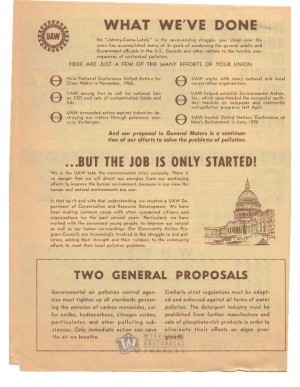

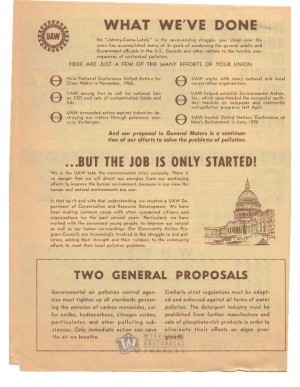

That brings us back to the first question of the quiz. The group most supportive of the first Earth Day organizing effort — financially and otherwise — was none other than the United Auto Workers.

A labor union not generally thought of for championing environmental causes, the UAW donated funds for the event and turned out volunteers across the country.

A labor union not generally thought of for championing environmental causes, the UAW donated funds for the event and turned out volunteers across the country.

UAW President Walter Reuther pledged his union’s full support for Earth Day and for subsequent air quality legislation that the auto industry staunchly opposed.

“What good is a dollar an hour more in wages if your neighborhood is burning down?” he said. “What good is another week’s vacation if the lake you used to go to is polluted and you can’t swim in it and the kids can’t play in it?”

Sensing a political shift, General Motors president Edward Cole soon thereafter promised “pollution-free” cars by 1980. (That didn’t pan out so well.)

Golden era of environmental regulation

Remember the mystery quote?

That was said by President Richard Nixon during his 1970 State of the Union address.

Yes, that Nixon, the conservative Republican most commonly remembered for prolonging America’s involvement in Vietnam and resigning in disgrace over the Watergate scandal.

But Nixon also oversaw the most sweeping environmental regulations in the nation’s history.

Even before the first Earth Day, Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act, which among other things, required environmental impact statements for major new building projects and developments. Nixon signed it into law on Jan. 1, 1970.

Environmentalism had never been one of Nixon’s major political priorities, but his administration — like the UAW — recognized the shifting political tide, as public outcry and media attention to environmental issues increased. It also didn’t hurt that at the time both the House and Senate were controlled by Democrats.