But he says the community has stepped up. For instance, a local foundation called to ask what the food bank needed.

"And I said, ‘I need a 40-foot cargo container and 10 feet tall, 10 feet wide, that's insulated.’ And it was here in three days,” he said.

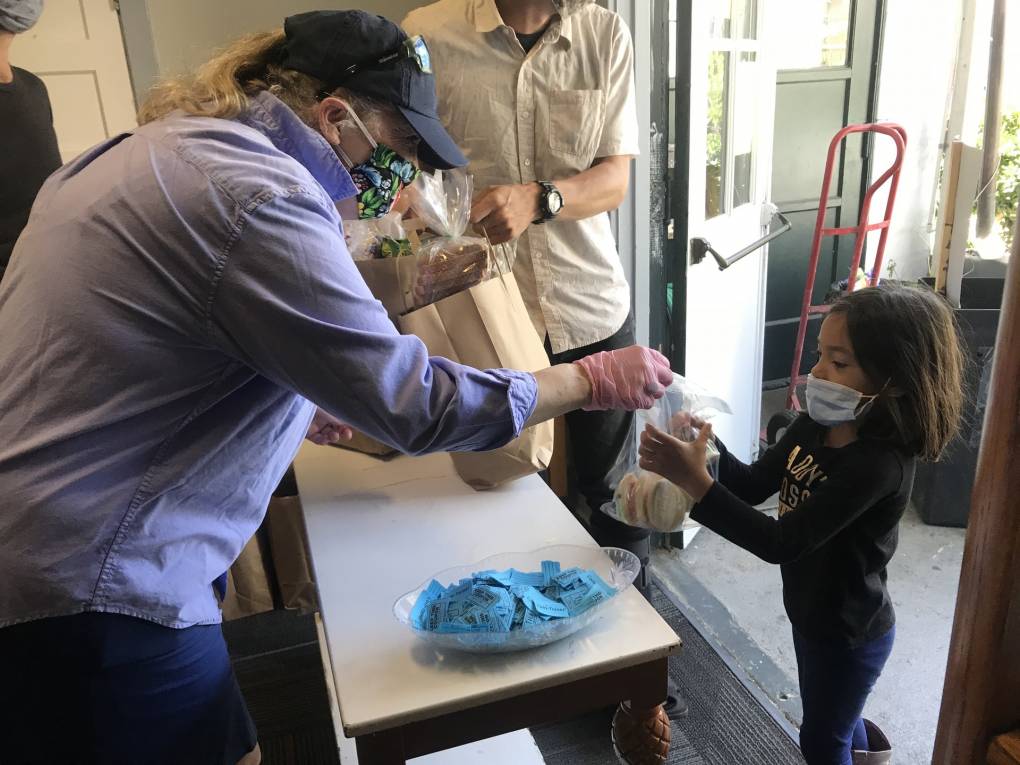

Scores of volunteers have shown up to help, as many as 90 in a week. Jeffrey says the bank has enough food to hand out, but has encountered a problem I never considered.

“One thing we're having a real problem with is bags to pack because they have to be sterile," he said. "The grocery stores are out of bags. And we just barely made it through this month.”

Trinity County has two main towns — Weaverville, with about 3,500 people, and Hayfork, with about 2,500. Both have grocery stores and a handful of restaurants are open for takeout or delivery.

But I know from my 2017 visit just how isolated most of this county is. Back then, I rode along as Jeffry maneuvered around potholes to get to the most remote drop-off point, a tiny town called Zenia, on the border of Humboldt County.

He told me about a run a few winters ago, when he defied Caltrans workers and drove a closed, snow-covered road to deliver food to people who’d been stuck there for months.

“I said, ‘I have to go.’ I slipped, lost traction, gained traction. I just knew they needed the food so I decided to take the chance and I made it,” he said.

Lauren Turner, who came to the food drop off at the volunteer fire department in Zenia, said she was grateful for efforts like that.

“It’s not easy up here,” she said. “Usually it’s 100 miles in any direction from here to a large town where you can buy groceries” — more than a two-hour drive, one way, to Eureka or Redding.

Jeffry said that for him, the work is really personal. Many years ago, he struggled with addiction and unemployment. “It just felt so good to be able to go to a place when you’re hungry,” he said.

He remembers his first meal in a soup kitchen. “It was in a church. It was spaghetti, garlic bread and a salad. and I’m so happy to be able to turn the table and be able to help people that might have been in my shoes before.”