Wagle said the woman on the phone, after looking at her application, said, “Oh well you should just do PUA, it will be faster.”

Wagle disagreed. “I said, ‘No, like, I really do qualify for unemployment insurance under AB 5,’ ” she said.

Wagle went back and forth with the woman on the phone. “Then finally she says, ‘Listen, you want my advice, just apply for the PUA. It’s going to take time. What are you going to do? Are you going to get a lawyer, try to like fight your case for you?’ ”

There are numerous reasons drivers like Wagle want state unemployment insurance instead of PUA.

First, it’s almost certainly more money. UI is awarded based on gross income, how much total income you bring in before expenses. PUA is calculated on net earnings, what you earn after all expenses are deducted. In both case, higher earnings equal more benefits. Drivers have tons of expenses — gas, wear and tear on their car, phone bills — meaning their gross is much higher than their net earnings, which means they would earn more money through UI instead of PUA.

Second, there’s concern over how long the PUA funding will last compared to UI benefits. Both are set at 39 weeks right now, but it would be up to the federal government to extend PUA and up to California to extend UI. Drivers worry that if the pandemic continues, the federal government will be less likely than California to extend the assistance.

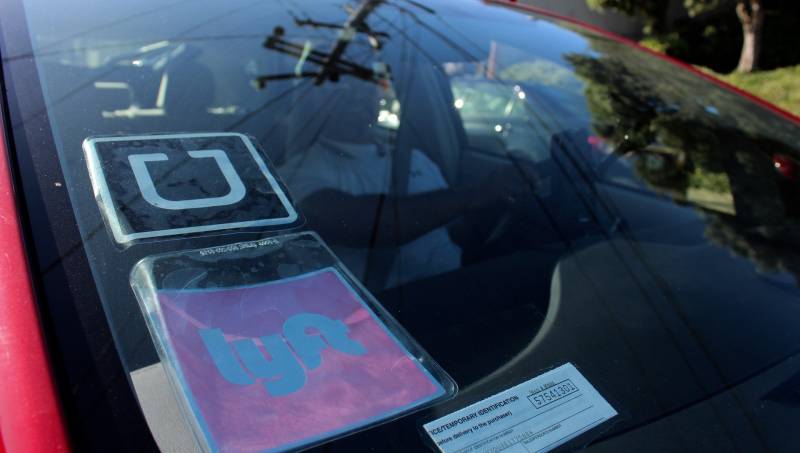

There’s also a question of who pays for the benefits. UI is covered in part by employers, and PUA money is coming from the federal government. Wagel considers herself a Lyft employee, so she says it is only fair that her employer pays some of the cost instead of federal tax payers. Since Lyft and Uber haven’t paid into the unemployment fund yet, the state would cover the costs, but it would be known that the companies owe California that money.

For these reasons, Wagel has been resisting the temptation of applying for PUA and fighting to get UI. But it’s been a hard fight.

Wagle desperately needs the money. She’s been without work for almost two months. And after all this time fighting to get UI, she’s worn down. The phone call with the woman at the EDD was the last straw.

“I just caved,” Wagle said. “As soon as I got off the phone with her I was like, aw fuck it. I am just going to go apply for this PUA. What am I going to do? I have to pay rent. I have to pay bills. I am just swimming here. So I am just going to take the bone that I am thrown. It’s still not right. It’s not right.”

Persistence and Luck

While Wagle finally settled for PUA, other drivers have actually gotten through and received UI. It has taken a lot of persistence, and what some drivers say feels like luck.

To get UI, a driver has to apply, get told they qualify for zero dollars because their employer did not report earnings or contribute to the fund, then appeal that finding, and finally go through an audit where they have to prove to a representative of the EDD how much they earned and that they should be classified as an employee, not a contractor.

Numerous drivers have posted on social media about getting UI. KQED spoke with one driver in Daly City who had gone through this whole process and who doesn’t want to use his name for fear of Uber kicking him off the app. He says his trick was not waiting for any kind of confirmation from the EDD, but instead filling out the online form and then sending a package with all of his documentation by certified mail.

He sent that package a month ago and then he says he just waited and prayed. Then, last week, he got a call from an EDD auditor. She asked him a few questions, and then said he was approved. He was watching online as fellow drivers were filling out online forms, being put on hold for hours when they called and getting nowhere. He said it seemed like a miracle that his claim went through.

The driver in Daly City says he is getting the max in state benefits: $450 a week. He is so happy to have finally gotten some income. He has a family of five to support. But he didn’t want to give up and settle for PUA instead of UI because he didn’t want federal taxpayers to contribute to his unemployment when Uber and Lyft weren’t.

“With the AB 5, we’re entitled to get the normal UI with the corporations of Uber-Lyft helping,” he said.

Conflicting Advice

A number of drivers KQED spoke with complained about getting conflicting information from the EDD, either by phone or on the website, about what to apply for and how. The EDD did not respond to a request for comment.

Carole Vigne is a senior staff attorney at Legal Aid at Work, a nonprofit that is helping drivers get UI. She says it is disappointing that a EDD representative would tell a driver to apply for PUA instead of UI.

“Under California law,” she said, “misclassified independent contractors or gig workers all should be on unemployment insurance.”

Vigne said while it is right for drivers to apply for UI, the state is losing money by covering Uber and Lyft’s bills.

“Eventually when this calms down,” Vigne said, “we anticipate that the state will go after these companies who haven’t paid into the fund, who haven’t been reporting earnings on behalf of workers so that the fund could be paid back.”

Years of Legal Battle

When the pandemic hit, Uber and Lyft had already been battling for years to continue classifying their workers as contractors. The companies had used the arbitration clauses in their contracts to settle countless legal disputes with workers over classification individually and behind closed doors.