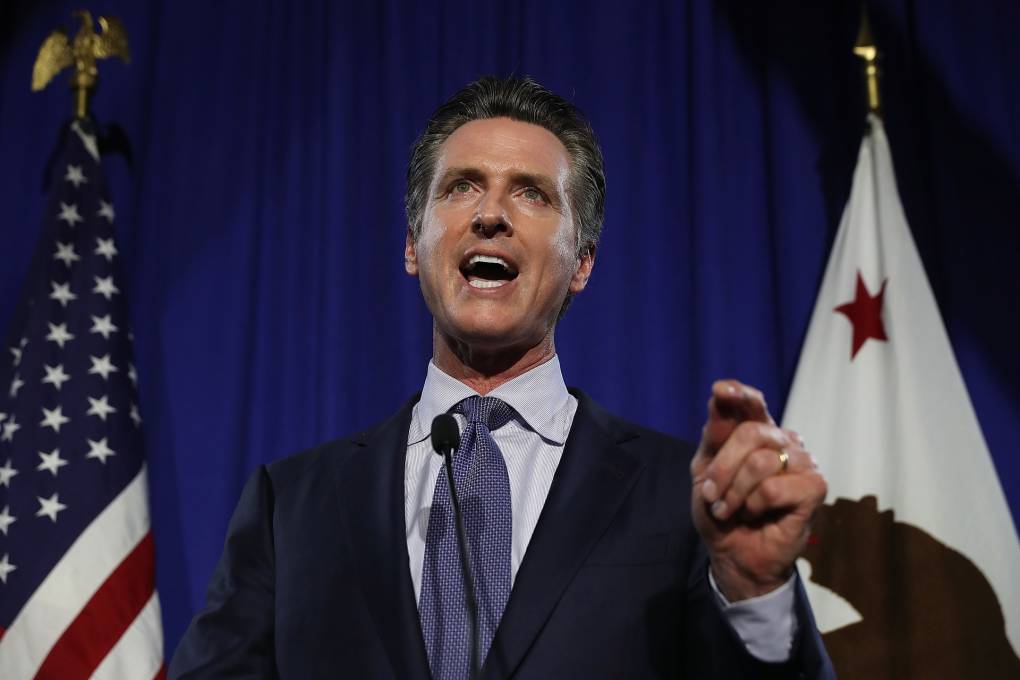

As the state Legislature takes up Gov. Gavin Newsom’s budget — the one with $19 billion less than before the coronavirus pandemic struck — some legislators say they’re hoping to put to use lessons learned from the last state budget crisis in hopes of avoiding some of the same mistakes.

Mark Leno was elected to the state Senate in 2008, just as the economy was in free fall. What he remembers are the lines of people who came to the state Capitol to plead for their favorite programs before the Health and Human Services budget subcommittee.

“That’s the committee where those cuts are made and hundreds of people make their way from throughout the state to line up at public comment to get a minute or two or three to tell us they’re very sad. Real-life tales. You see the faces, you see the tears and you hear the cries for help,” Leno said recently.