Wolfrum said she’s doubtful that the app will be useful, both because of people's wariness and its poor performance. She gave it a bad review on Google’s app store after it failed to notice lengthy shopping trips she made one weekend to Walmart and Target stores.

North Dakota is now looking at starting a second app based on the Apple-Google technology. “It was rushed to market,” because of the urgent need, Vern Dosch, the state’s contact tracing facilitator, told KFYR-TV in Bismarck. “We knew that it wouldn’t be perfect.”

The ACLU is taking a more measured approach to the Apple and Google method, which will use Bluetooth wireless technology to automatically notify people about potential COVID-19 exposure without revealing anyone's identity to the government.

But even if the app is described as voluntary and personal health information never leaves the phone, the ACLU says it’s important for governments to set additional safeguards to ensure that businesses and public agencies don’t make showing the app a condition of access to jobs, public transit, grocery stores and other services.

Among the governments experimenting with the Apple-Google approach are the state of Washington and several European countries.

Swiss epidemiologist Marcel Salathé said all COVID-19 apps so far are “fundamentally broken” because they collect too much irrelevant information and don't work well with Android and iPhone operating software. Salathé authored a paper favoring the privacy-protecting approach that the tech giants have since adopted, and he considers it the best hope for a tool that could actually help isolate infected people before they show symptoms and spread the disease.

“You will remember your work colleagues but you will not remember the random person next to you on a train or really close to you at the bar,” he said.

Other U.S. governors are looking at technology designed to supplement manual contact-tracing efforts. As early as this week, Rhode Island has said it is set to launch a contact-tracing database system mostly built by software giant Salesforce, which has said it is also working with Massachusetts, California, Louisiana and New York City on a similar approach.

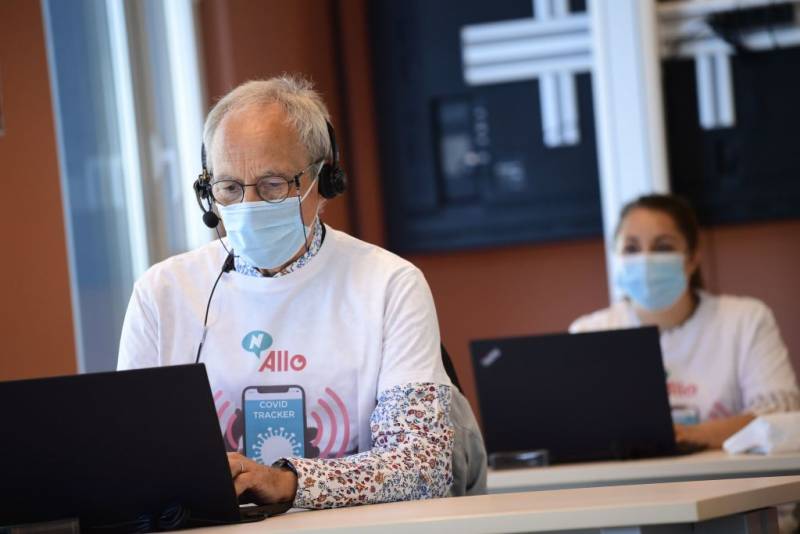

Salesforce says it can use data-management software to help trained crews trace “relationships across people, places and events” and identify virus clusters down to the level of a neighborhood hardware store. It will rely on manual input of information gathered through conversations by phone, text or email.

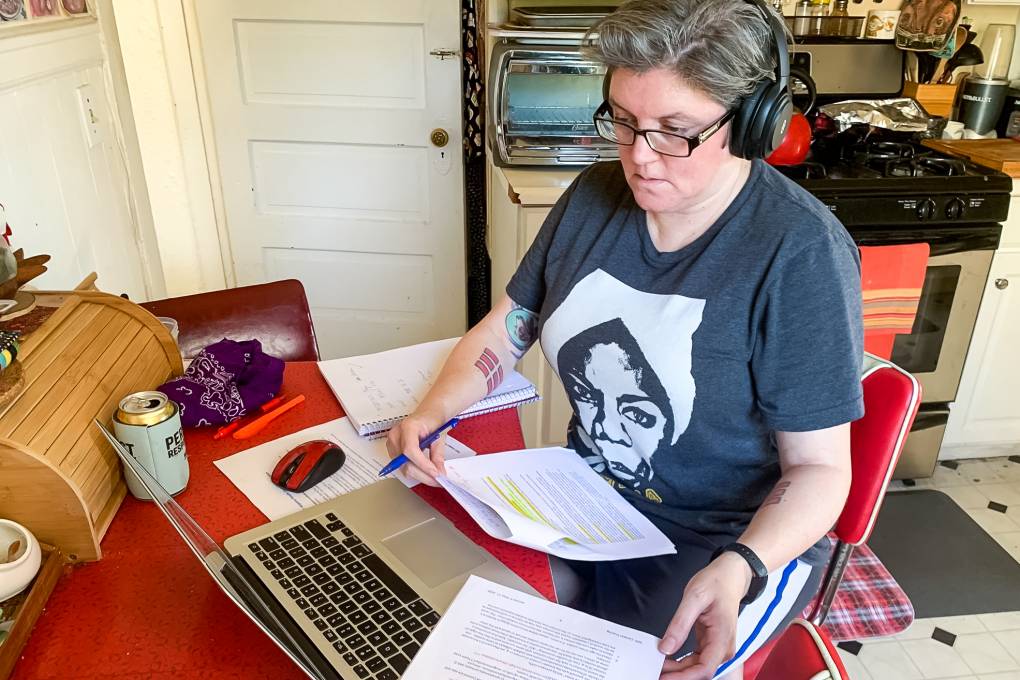

“It’s only as good as a lot of us using it,” Rhode Island Democratic Gov. Gina Raimondo said at a news conference last week. “If 10% of Rhode Island’s population opts in, this won’t be effective.” The state hasn't yet outlined what people are expected to opt in to.