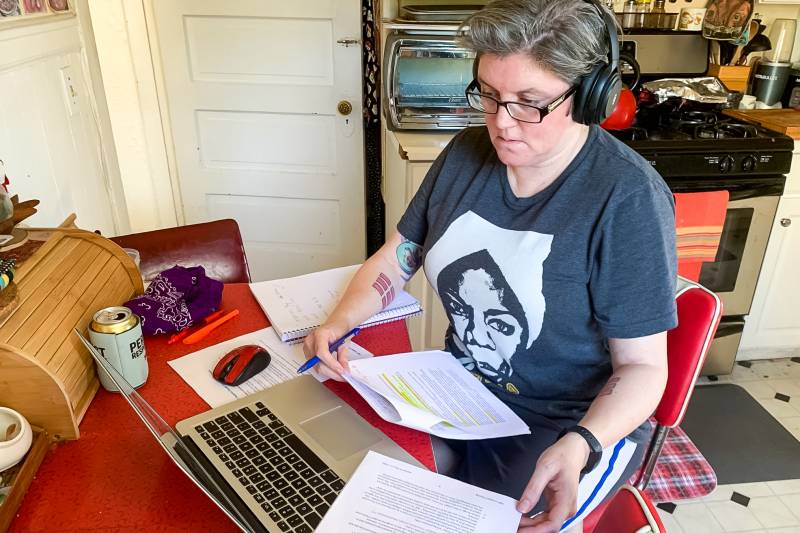

Or they’re teens afraid to admit out loud that they’re looking for books about sex or queer identity. Fagundes is used to coaxing it out of them in a calm, nonjudgmental way. It’s the same with contact tracing: asking people about their health status and history.

“Talking about sensitive subjects is a natural thing for librarians,” she says. “It’s a lot of open-ended questions, trying to get people to feel that you’re listening to them and not trying to take advantage or put your own viewpoint on their story.”

Fagundes is part of the first team of contact tracers trained through a new 20-hour virtual academy led by UCSF. California awarded the university an $8.7 million contract this month to expand the academy and train 20,000 new contact tracers throughout the state by July, one of the largest such efforts in the country. Gov.Gavin Newsom has said counties need 15 contact tracers for every 100,000 residents to adequately contain the virus after shelter-in-place orders are lifted. Nationally, experts have estimated the U.S. needs between 100,000 and 300,000 contact tracers.

With many people staying home in recent months, counties that haven’t yet built their contact-tracing teams to pandemic levels have generally been able to manage caseloads. Each new person who tests positive for COVID-19 has been in contact with an average of four or five people while infectious — usually family members and neighbors — according to local health officials. But as counties begin allowing businesses to reopen, a person’s average contacts will go up to 40, necessitating a larger team to identify and call them.

“You have a four- or five-day window to find people and get them isolated, which is what we do instead of treat them because we don’t have treatment for COVID,” says George Rutherford, a professor of epidemiology at UCSF who’s been leading the training effort.

Librarians, Tax Assessors, Paralegals

The new training program takes place over the course of five days and involves lessons on epidemiology and motivational interviewing, and demonstrations of contact tracing phone calls. In addition to librarians, San Francisco has been asking government employees from county tax assessor and city attorneys’ offices to help out, including financial analysts, paralegals and investigators. Some rural counties have also been recruiting sheriff’s deputies for the job.

“The major qualification is being able to talk to people,” Rutherford said. “In other states they love to pick up people who worked as airline reservation agents, because they’re used to talking to people all day long and trying to work things out for them.”