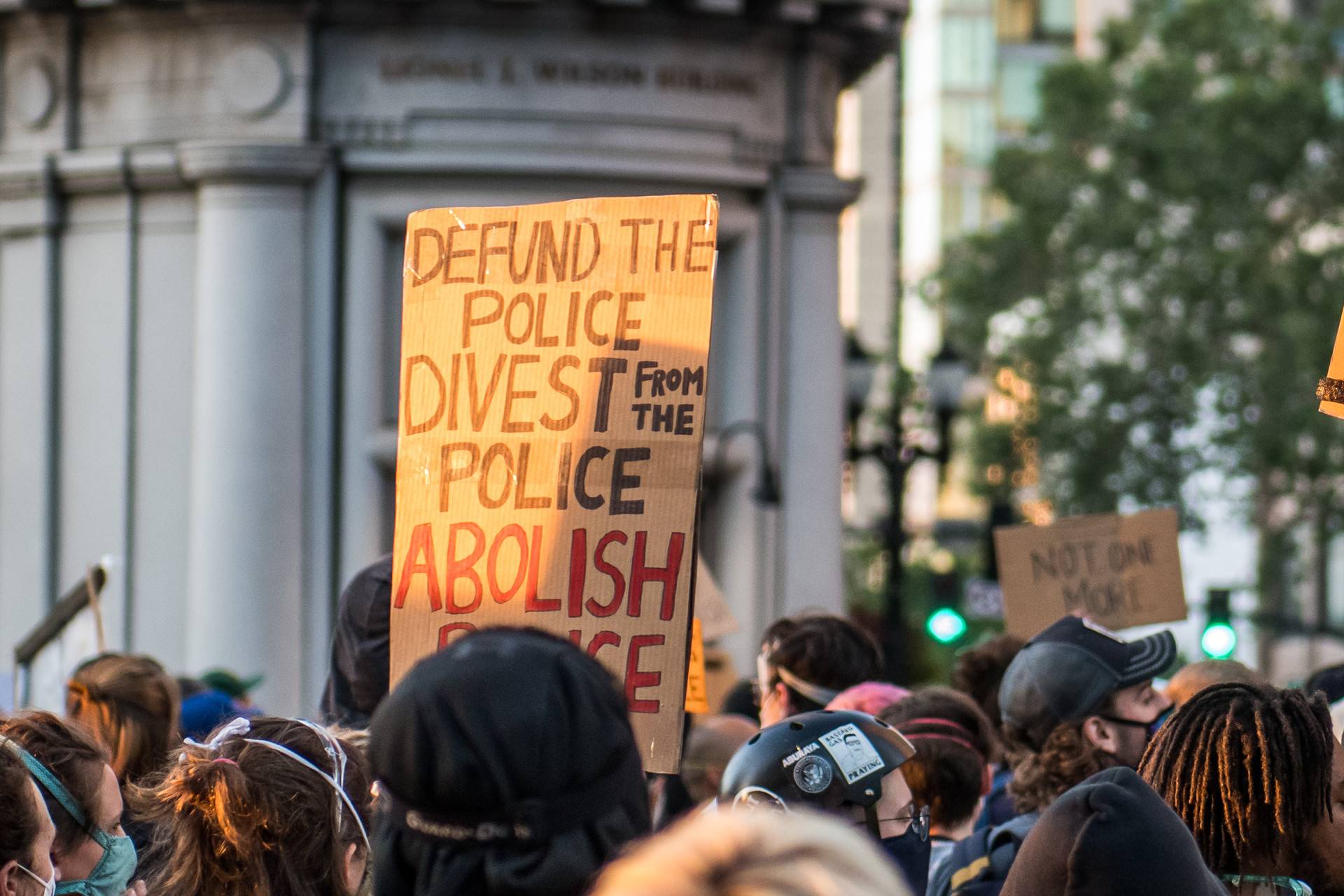

Among the tens of thousands of Black Lives Matter protesters who continue to pour into the streets of cities across the country — and the world — decrying America's long history of violent, racially unjust policing, one rallying cry has gained particular traction: 'Defund the police.'

But what that actually means varies widely depending on who you ask, from dismantling or flat-out abolishing existing police forces to slashing their hefty budgets and diverting those funds to social service programs, which proponents say would much better serve and protect many communities.

Broadly speaking, 'defunding the police' entails minimizing the outsize role law enforcement has come to assume in most U.S. cities as the default responder for all matters of complaints, and delegating many of those responsibilities to unarmed social workers and other behavioral health specialists.

“When we talk about defunding the police, what we’re saying is, ‘Invest in the resources that our communities need,'” Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza said recently on NBC’s “Meet the Press." So much police response, she added, “is directed toward quality-of-life issues, homelessness, drug addiction, domestic violence and conflict.”

As local leaders scramble to institute police reforms — from banning chokeholds to heightening accountability — many activists argue those tweaks won’t ultimately fix a system they consider fundamentally unjust. Real change, they contend, can only come about through a sweeping process of tearing down police departments and rethinking public safety.