This story was reported in collaboration with KQED in San Francisco and WLRN Public Media of South Florida.

O

n Friday, March 13, President Donald Trump and Vice President Mike Pence stood in the White House Rose Garden to declare COVID-19 a national emergency. But the risk of the disease, Pence told the nation, remained low.

“We don’t want everybody taking this test; it’s totally unnecessary,” Trump assured Americans. “This will pass.”

About 1,000 miles south of Washington, as if heeding their call, thousands of spring breakers had converged on Miami Beach. They played tug of war on the sand and snapped selfies by the water.

“If I get corona, I get corona,” one tourist from Ohio told reporters. “At the end of the day, I’m not gonna let it stop me from partying.” For them, the specter of the COVID-19 pandemic seemed very far away.

Like Trump, Florida’s Republican governor, Ron DeSantis, had downplayed the threat of COVID-19. Just a few days earlier, when Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s leading expert on the pandemic, had said Florida was experiencing community spread of the virus, DeSantis had retorted that it wasn’t true. The governor also had balked at closing the state’s beaches to check the virus’ spread.

That weekend after Trump’s address, Miami Beach Mayor Dan Gelber took a stroll on Ocean Drive, a thoroughfare lined with palm trees and historic Art Deco buildings. He came to a sudden realization that not one person out of the thousands he saw was practicing social distancing. Without widespread testing, he thought, the virus could be silently spreading through his city.

It hit Gelber: He had to close the beach.

At that point, I realized that I was not going to rely on the federal government to tell us what to do,” he said. “I obviously couldn’t rely on the state.”

Across the country, Dr. Scott Morrow was experiencing his own day of dread. The veteran public health officer for San Mateo County, on California’s San Francisco Peninsula, Morrow had no proof that the virus was spreading. Medical testing supplies were maddeningly impossible to come by. But he had become convinced that the potentially deadly virus, which had first been noted in the area only six weeks before, was “spreading like wildfire under our noses.”

Morrow feared that the entire San Francisco Bay Area, a region of more than 7 million people, would soon be “following Italy into the abyss,” with an exponential growth curve of infection and death.

Worse, Morrow was running out of ideas for checking the contagion. Already, he had banned large public gatherings. The county’s schools were shutting down. Deeply frustrated, he recalled sending an email to county officials, warning them, “This is all I can do – I’m out of options.”

On a rainy Sunday morning two days later, Morrow was awoken by a text message: Would he jump on a call with Dr. Tomás Aragón, the public health officer in San Francisco, and Dr. Sara Cody, the health officer of Santa Clara County in the hard-hit Silicon Valley?

In a day of calls that soon included county counsel, the officers converged on a radical consensus — to use their broad powers under California public health law in a way that had never been tried in the United States. To stop the spread of the disease, they would order the public to stay in their homes and shelter in place.

“This is what needed to be done,” Morrow said. Bay Area health officers announced vast shutdown orders the next day.

Morrow recalls feeling “scared shitless.” Would the public comply with shelter in place? And even if they did, would it work?

A week and a half later, on March 26, the U.S. became the global epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Blunting the Pandemic

At a congressional hearing in mid-May, a recently ousted federal health official pulled back the curtain on the colossal missteps that had undercut the federal response to the pandemic. Rick Bright had filed a whistleblower complaint charging that he was removed from his post as the deputy assistant secretary for preparedness and response at the Department of Health and Human Services when he urged the vetting of hydroxychloroquine, the anti-malaria drug Trump touted as a cure for COVID-19.

Bright testified that he and several colleagues had warned the White House as early as January that the country was unprepared for a pandemic.

We knew going into this pandemic that critical medical equipment would be in short supply,” he told Congress on May 14. “I was met with indifference, saying they were either too busy, they didn’t have a plan, they didn’t know who was responsible for procuring those.”

The federal government not only had failed to secure critical supplies, such as ventilator masks and testing swabs, he said, but had failed to provide clear guidance to the nation.

"Our population is being paralyzed by fear,” he said, “stemming from a lack of a coordinated response and a dearth of accurate, clear communication about the path forward.”

The testing shortages, in particular, hampered public health officials as they tried to confront the looming threat, said Dr. John Swartzberg, an epidemiologist with the joint medical program of the University of California, Berkeley and UC San Francisco. For epidemiologists, tests are “our eyes” in a pandemic, Swartzberg said, and the rollout was so badly botched that decision-makers were left in the dark.

At first, testing was delayed because the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention chose to create its own test rather than partner with private labs. When the new CDC tests were finally ready, the agency failed to ramp up production – and the tests themselves had technical defects. State labs had to send their samples to CDC headquarters in Atlanta, causing a long backlog.

"States can do their own testing,” Trump would later say. “We’re the federal government. We’re not supposed to stand on street corners doing testing.”

Response to the pandemic in the global epicenter would be left to states and cities.

The earliest states to be hit by the pandemic would face the toughest tests, forced to consider unprecedented decisions. Among the first states with confirmed cases — and confirmed deaths — were California and Florida, whose governors’ wildly different leadership styles influenced the states’ responses.

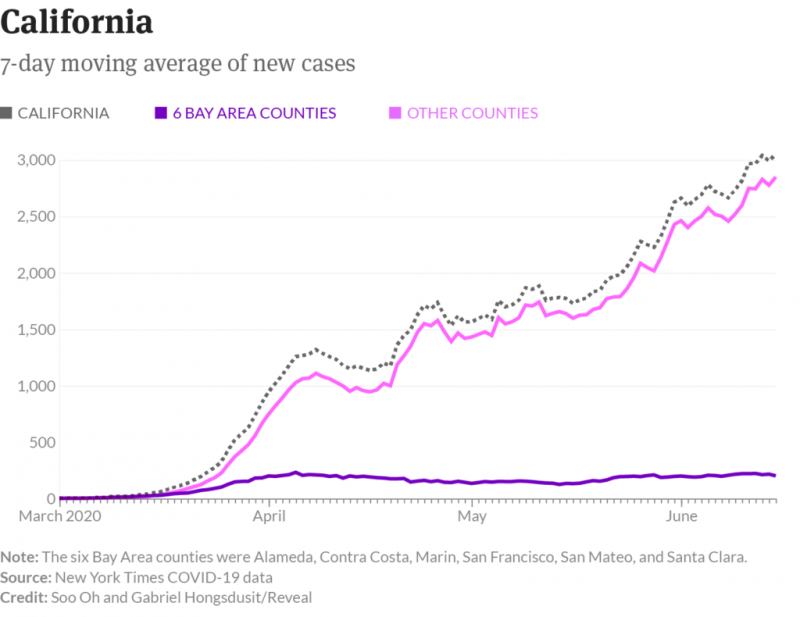

California Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, ultimately followed the lead of local health officers and became the first in the nation to extend shelter-in-place orders to the entire state.

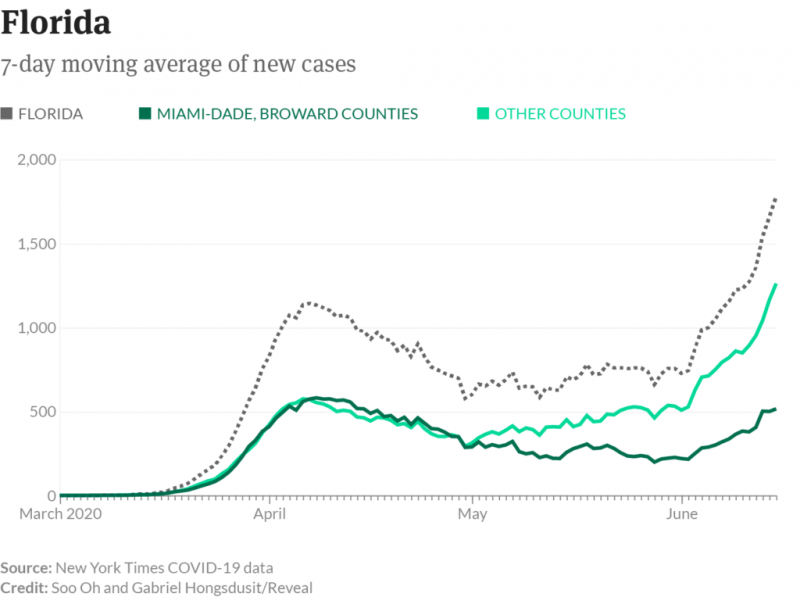

In Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, issued only vague recommendations until late in the game, leaving local governments in charge of crucial decisions. He refused to close all of the state’s beaches and delayed issuing a statewide stay-at-home order for weeks, until 36 states had already done so and Florida had surpassed 100 deaths. In a statement to Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting, DeSantis spokesperson Cody McCloud said “the Governor’s Office worked with these mayors to ensure the needs of their counties were being met” as they made decisions early on in the pandemic.

Nowhere was the federal government’s scattershot response to the pandemic — and the contrast between the two governors — on more vivid display than in the distinct fates of cruise ship outbreaks that ended up in California and Florida ports.

The California-bound liner, the 3,500-passenger Grand Princess, had one COVID-19 death and nearly two dozen other cases by the time it approached San Francisco Bay in early March. Trump had made clear that he wasn’t keen on the ship coming ashore, concerned it would inflate the nation’s COVID-19 caseload.

“I like the numbers being where they are,” he said March 6. “I don’t need to have the numbers double because of one ship that wasn’t our fault.”

Newsom feared that if the ship docked in San Francisco, infection might sweep through the city. After prolonged consultations with the CDC, Pence’s coronavirus task force and other federal health officials, Newsom announced a plan: The Grand Princess would dock in Oakland, and U.S. passengers would be put into quarantine at a cluster of military bases.

Florida’s cruise ship crisis involved 1,200 passengers on two Holland America liners, the Zaandam and the Rotterdam. Some 150 passengers had developed flu-like symptoms by the time Port Everglades became the ships’ last resort.

Here, DeSantis left decision-making in the hands of a unified command of eight local and federal agencies. That team, as in California, included the CDC. But the outcome could not have been more different.

On April 2, when the ships were allowed to dock, 13 seriously ill passengers and one crew member were taken to hospitals. Without being tested or quarantined, the other passengers headed for the airport, where they boarded chartered flights to such major cities as Atlanta, Toronto, London — and San Francisco.

The distinct pandemic responses in California and Florida were also shaped by the two states’ vastly different health infrastructures. While in California, counties have independent and highly autonomous health officers, Florida has a more centralized health department with branch offices in each county. The department largely takes orders from the governor. If the state’s leadership is slow, so is the department’s response.

Florida Department of Health officials declined an interview to discuss their pandemic response, noting in a statement only that their approach has been “strategic and methodical.”

Reveal, in partnership with KQED in San Francisco and WLRN Public Media of South Florida, interviewed dozens of elected officials, public health officers, mayors, hospital directors and educators to provide an unprecedented look at how key decisions made by local officials ultimately saved lives as the Trump administration downplayed the threat of the virus in the early days of the pandemic.