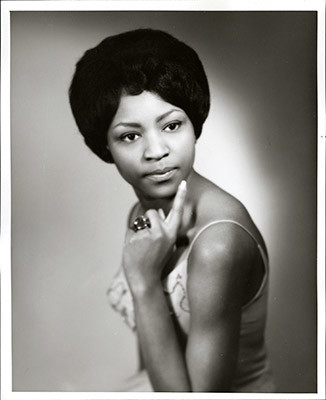

If you were walking down San Francisco’s Fillmore Street in the 1950s, chances are you might run into Billie Holiday stepping out of a restaurant. Or Ella Fitzgerald trying on hats. Or Thelonious Monk smoking a cigarette.

This wouldn’t be out of the ordinary in the “Harlem of the West.”

Musician Terry Hilliard started playing at venues in the Fillmore District when he was a student at San Francisco State.

“[The Fillmore] was a place where talent could be developed, whether it be music, art, dancing or whatever it was … it was a place where you could express yourself and be accepted by others and you had an audience,” says Hilliard.

But, Hilliard says he doesn’t see that kind of culture anymore today.

To understand why the music scene in the Fillmore has changed, you have to go back to when so many of San Francisco’s stories begin: the 1906 earthquake.

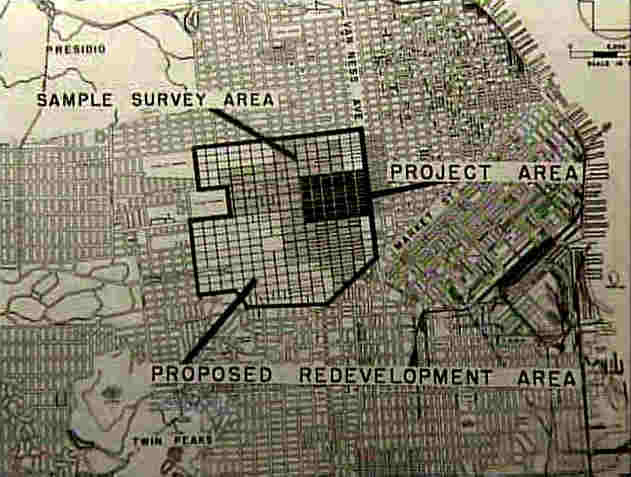

The Fillmore District, today known as the area defined by Turk Street and Geary Boulevard (its boundaries have changed over the years), was one of the few neighborhoods in San Francisco that survived the earthquake and fire that leveled much of the city.

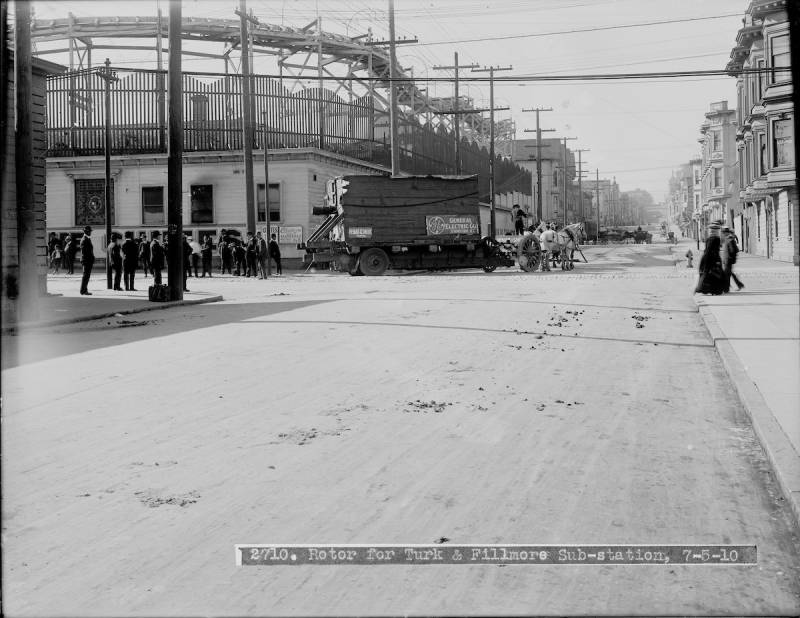

In her book, “Harlem of the West”, author and filmmaker Elizabeth Pepin Silva describes how the Fillmore became the city’s shopping and political center while Market Street was rebuilt. Wanting to capitalize on the neighborhood’s new popularity, the Fillmore Neighborhood Merchants Association decided the district would also become an entertainment center. In 1909, the Fillmore Chutes amusement park was built and three years after that, the famous Fillmore Auditorium (which was the subject of another Bay Curious episode because they give free apples to their guests.)

“It was a really fun, exciting place,” says Silva. “But it was mainly for white people.”

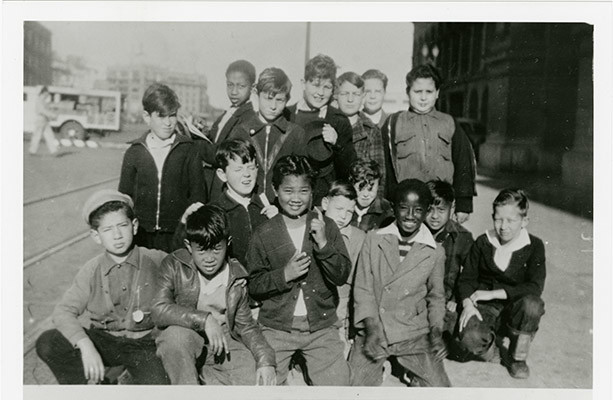

San Francisco in the early 1900’s was segregated, but in the Fillmore it was a bit different. The earthquake had damaged a lot of neighborhoods where people of color were “allowed” to live in the city, but the surviving Fillmore District had inexpensive real estate and a history of accepting immigrants. Through the early 1900s up until the 1940s, you had Filipinos, Mexicans, African Americans, Russians, Japanese Americans and Jewish people living next door to one another.

“It became known as one of the most integrated neighborhoods west of the Mississippi,” says Silva.

A Changing Neighborhood

Then, Pearl Harbor was bombed on December 7, 1941. Japanese Americans were forced out of their homes and into concentration camps. Simultaneously, African Americans from the Midwest were given free train tickets to come work the shipyards in San Francisco and Richmond, Calif.

African Americans arriving in San Francisco moved into empty apartments the Japanese Americans had been forced out of. Between 1940 and 1950, the Black population of San Francisco grew tenfold. By 1945, some 30,000 African Americans were living in the city.