But racial disparities are also prevalent in efforts to keep Black Californians off the streets once they’ve been rehoused. An analysis of Black homelessness in Los Angeles County found that while Black people were rehoused at the same rates as other ethnic groups, they were more likely to return to homelessness than any other demographic.

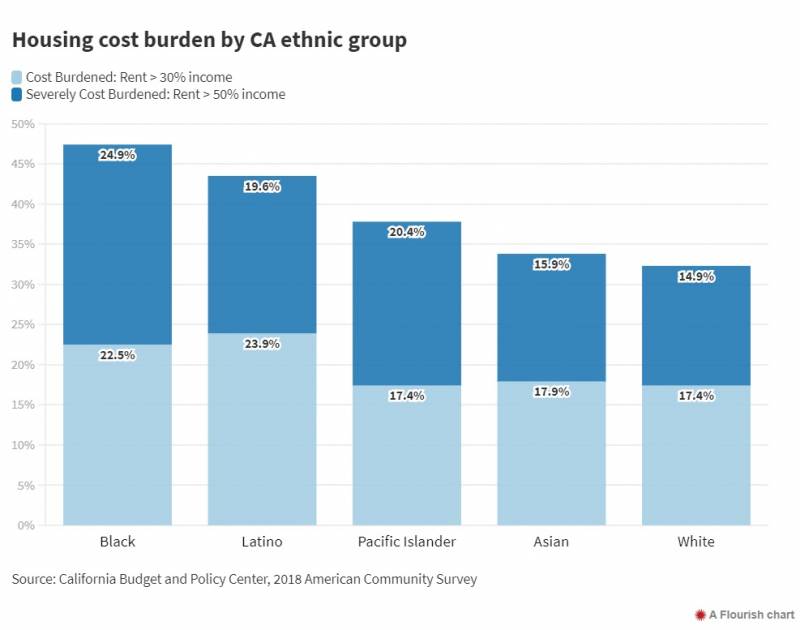

Housing cost burden falls on Black Californians

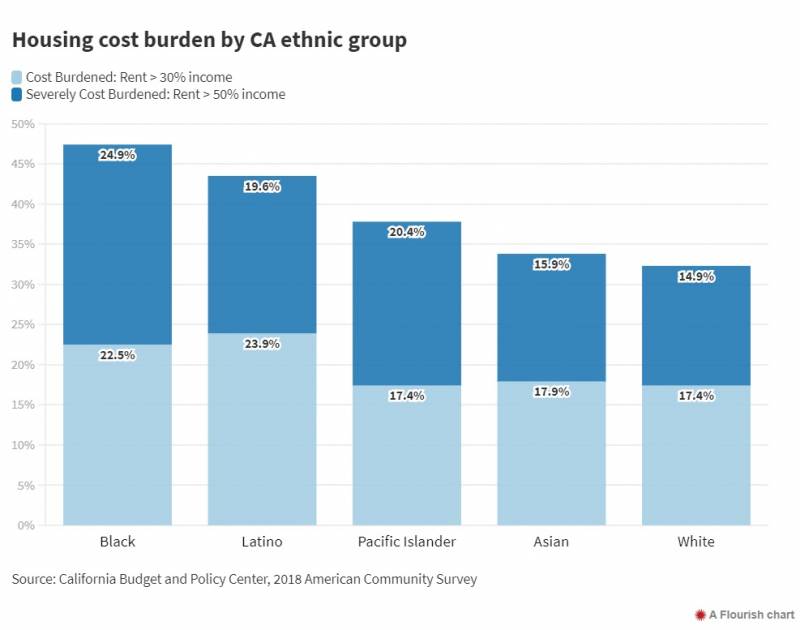

California is an extremely expensive state. More than 40% of its households fit the federal definition of “housing cost-burdened,” with rent or mortgage payments eating up more than 30% of residents’ income.

On average, Black Californians see a larger chunk of their paychecks going to housing costs than any of the state’s other major demographic groups. Nearly 50% of Black Californians lived in households that were cost-burdened in 2018; nearly a quarter paid more than 50% of their income towards housing costs.

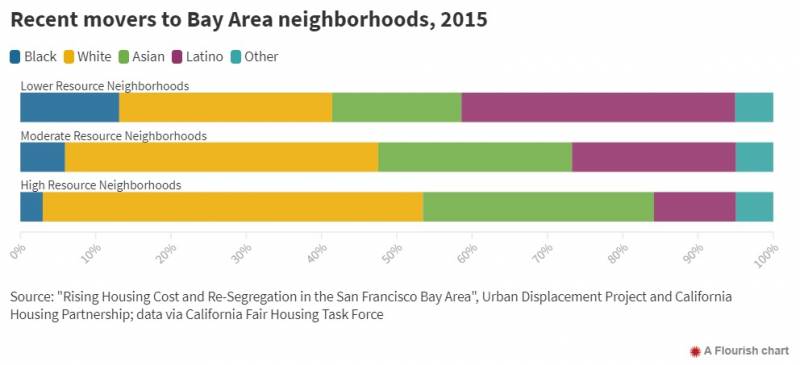

Black households pushed to suburbs

When comparing how far apart Black, white and other ethnic groups live from one another, California cities are typically less segregated than their counterparts in the Northeast or Midwest. Most parts of the state have also seen improving rates of residential integration over the past half-century, mirroring a national trend.

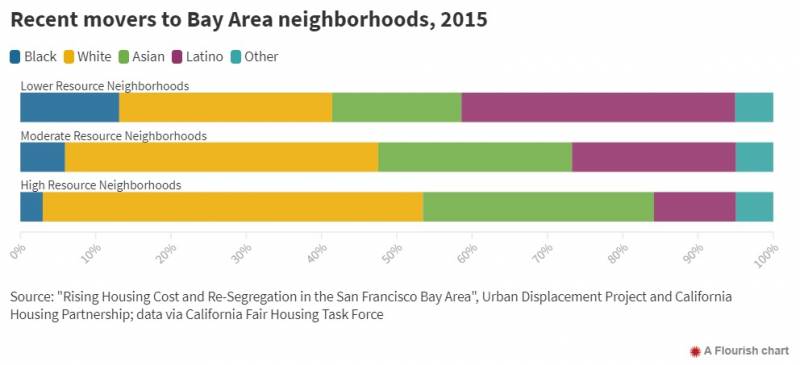

But part of the decline in California racial segregation is driven by gentrification and displacement pressures upon Black communities in urban cores.

It’s not just more affluent, younger, white Californians moving into recently redeveloped downtowns that are paradoxically driving down segregation rates. Rapid accelerations in housing costs over the past few decades have driven many Black renters out of larger coastal cities and into older, formerly predominantly white suburbs. While the Black populations of parts of major cities like Los Angeles and Oakland have declined, far-flung suburbs like Palmdale in Southern California and Antioch in the Bay Area have seen rising numbers of Black families.

“African Americans and to a lesser extent Latinos are moving to suburban areas at the fastest clip we’ve observed since the civil rights era,” said Michael Stoll, professor of public policy at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs.

While more diverse now than they were in the mid-20th century, these suburbs are not the high-opportunity enclaves associated with high-quality school systems and upward economic mobility. And Stoll stresses that continued patterns of segregation, gentrification and displacement have practical impacts for how white, Black and other ethnic groups view one another.

“There are consequences to segregation,” said Stoll. “There are questions around social cohesion, and that can’t be any more important than what we’re observing in the current debates we’re having around racial and social justice. It’s hard to become a socially cohesive place if people are living in different neighborhoods and not being able to communicate and work together around common interests.”

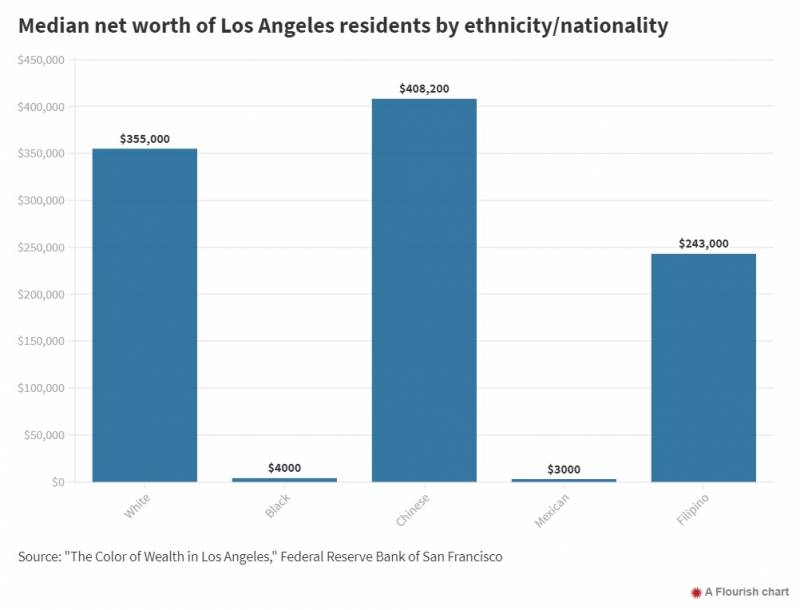

Wealth gap starker than income gap

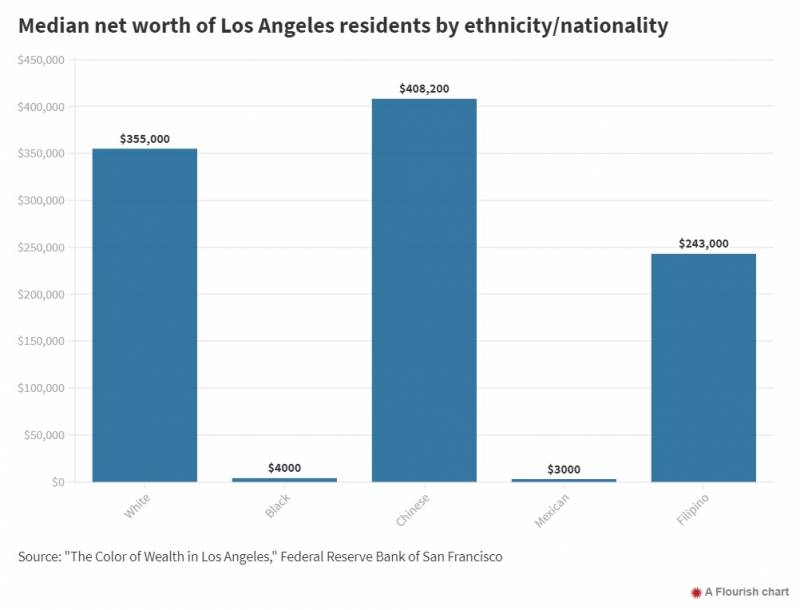

Income gaps aside, disparities in wealth are even starker — and more consequential.

“Wealth gives a cushion if something unexpected happens. If your car breaks down or something happens to your house, you don’t dip into your income, you dip into your savings” said Esi Hutchful, policy analyst at the California Budget and Policy Center. “It’s your wealth that allows you to invest in yourself, in your business, in the next generation.”

Reliable wealth data is unfortunately severely lacking at the state level. But results from one financial survey of households in the Los Angeles metro area illustrates just how dramatic the wealth gap is for Black households.

The key to wealth accumulation for most U.S. households is owning a home. That’s especially true in California, where skyrocketing home values have transformed homes in formerly middle-class neighborhoods into million-dollar nest eggs.

Those wealth gains have largely been accrued by non-Black homeowners. While more than 60% of white California households and 58% of Asian California households are homeowners, only 33% of Black households own the home they live in.

As predatory lenders disproportionately targeted Black would-be homeowners across the country, the late 2000’s foreclosure crisis decimated Black homeownership nationally. While homeownership rates have somewhat rebounded for other demographic groups, Black homeownership has flatlined (although very recent data suggest some gains).

Lost equity in Black homes

You can also see signs of systemic racism in the home values for Black households that do own homes

Homes in majority Black neighborhoods across the country are undervalued compared to equivalent homes in neighborhoods with few Black residents, controlling for factors like the quality of the local school district and access to neighborhood amenities like parks.

The San Francisco Bay Area has the largest equity gap of any major metro area in the country between comparable homes in comparable Black and non-Black neighborhoods: On average, homes in Black-majority neighborhoods are devalued by about $164,000. In the Los Angeles area, homes in Black-majority neighborhoods are devalued by about $70,000.

“You have appraisals, you have lending practices, you have real estate agent behavior,” said Andre Perry, researcher at the Brookings Institute. “We clearly see that there is discrimination baked in the practices that come out in the research.”

How the pandemic could exacerbate the housing crisis

The economic fallout from the novel coronavirus pandemic has added a new, pressing dimension to Black Californians’ housing crisis.

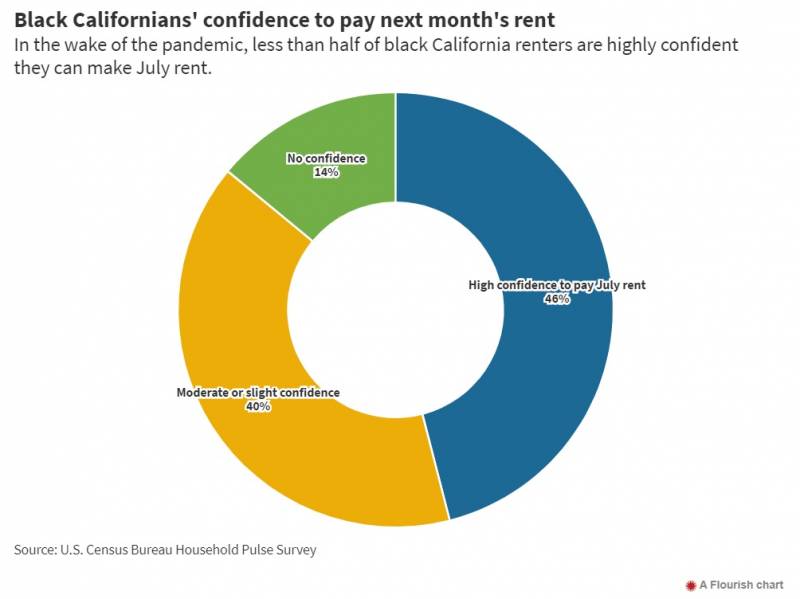

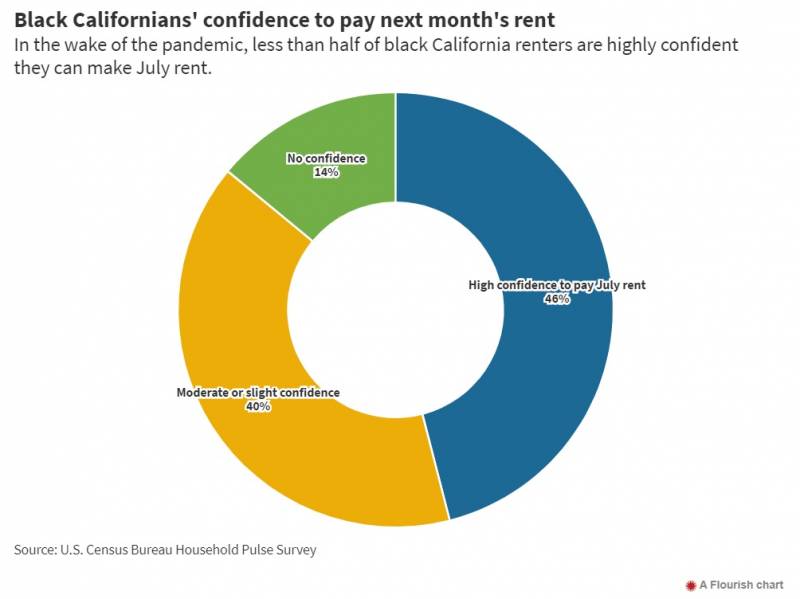

With Black households already disproportionately more likely to have high rent burdens, tenants’ rights groups fear a wave of evictions from missed rent payments could be coming as expanded unemployment benefits are scheduled to expire next month. In a Census survey conducted at the beginning of June, less than half of Black California renters who responded to the question expressed high confidence they would be able to make next month’s rent.

Lee says the pandemic has laid bare the racial divides the state has long struggled to close.

“These systems aren’t broken, this is how they were designed to work,” she said. “We’re catching up to the reality and understanding of how horrible that really is.”