The 4-3 ruling in Otsuka v. Hite left California with “a distinctly modern interpretation,” of infamous crimes, Holloway said — one judging that only threats to the ballot box should result in a loss of voting rights.

But as critics of the ruling predicted, the new standard of ‘infamous crimes’ was again difficult for local election officials to put into practice.

“By what standard is the Registrar of Voters to determine whether one convicted of crime is thereby branded as a ‘threat to the integrity of the elective process’?” wondered Justice Louis Burke, in his dissent. “For example, would murder qualify?”

Scattershot implementation of the ruling meant the decision to exclude Californians convicted of felonies would largely rest with county officials for the next decade.

Voters End Confusion with Proposition 10

A survey of California counties in 1972 found that voting rights for former inmates varied county by county. Some local election officials refused to restore voting rights to any former prisoner, others created a list of crimes resulting in permanent disenfranchisement — and still others considered each former inmates’ case separately.

Courts were also divided on the issue: the California Supreme Court ruled in 1973 that permanent voter exclusion following a conviction for an ‘infamous crime’ violated equal protections rights. A year later, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned that decision in Richardson v. Ramirez, ruling that convicted felons had no constitutional right to vote. The decision justified the disenfranchisement laws that now exist in dozens of states.

The issue was finally decided on the ballot. In 1974, the state Legislature put Proposition 10 before voters, which proposed to eliminate the “infamous crime” statue from the state constitution. In its place, it proposed the “disqualification of electors while mentally incompetent or imprisoned or on parole for the conviction of a felony.”

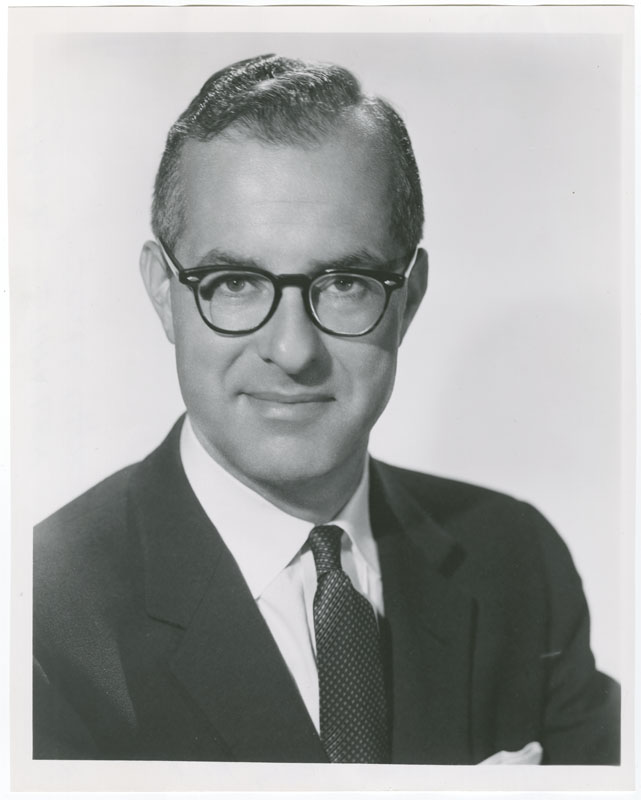

The measure was backed by Democrats, including San Francisco Sen. George Moscone and Los Angeles Assemblyman Julian Dixon. They argued against lifelong disenfranchisement, and sought to end the patchwork of county-level decisions on voting rights.

“The objective of reintegrating ex-felons into society is dramatically impeded by continued restriction of the right to vote,” they wrote in that year’s voter information guide.

The Los Angeles Times reported at the time that Proposition 10 was among the measures that “failed to cause much controversy during the fall election campaign.” And on Election Day, as California voters sent Jerry Brown to the governor’s office for the first time, Proposition 10 was approved with 56% of the vote.

That left California’s law on felon disenfranchisement as it exists today: voting rights can only be restored to those convicted of a felony upon completion of their parole term — a period of supervision following an inmates’ release from prison.

Democrats and groups like the League of Women Voters had succeeded in ending the uncertainty of the ‘infamous crime’ statute and moved the state away from lifetime disfranchisement of former inmates.

But as with so many California ballot measures, Proposition 10 carried an underlying consequence: by aligning disenfranchisement with any felony (instead of specific crimes that threatened the “integrity of the elective process”) it married suffrage to an expanding criminal justice system that disproportionately impacted Black and Latino Californians.

A Modern ‘Poll Tax’?

Over the ensuing decades, the number of Californians on parole for a felony skyrocketed. A report from the UC Berkeley School of Law found an incredible 708% increase in the state’s parole population between 1980 and 2010 — among the largest jumps in the nation over that period.

Jose Gonzalez is among the Californians whose parole term is set for life. He spent nearly two decades in state prison for his involvement in a murder as a teenager.

“By the time I was 17, I was already sentenced and sitting in a state maximum security adult facility,” Gonzalez said.

After his release, Gonzalez got a degree and is now working and raising his son, but his lifetime parole term prevents him from voting.

“As a taxpayer, as a regular person, you want to have a say,” Gonzalez said. “And if you feel like you don’t, then at the worst you’re not invested in your community. You don’t have that attachment.”

Black and Latino Californians are disproportionately represented among parolees, according to a study from the Public Policy Institute of California. By the end of 2016, Black Californians accounted for 6% of the state’s adult population, but 26% of the state’s parole population. And Latinos made up 35% of the adult population, but 40% of those on parole.

Assemblyman Kevin McCarty (D-Sacramento), the author of Proposition 17 on this year’s ballot, said the racial makeup of the state’s parole population makes the current punishment of disenfranchisement “really kind of like poll taxes.”

“If you look at the percentage of people who are on parole and can’t vote, they are people of color,” McCarty said. “California, for all our progressiveness, we’re really behind the curve on this.”

Progressives seeking to expand voting rights for formerly incarcerated Californians have chosen not to go as far as the arguments of the 1960s and 1970s, when jurists questioned the very premise of stripping voting rights for crimes that have no relation to the electoral process.

Instead, they have slowly chipped away at a declining population of disqualified voters. Recent criminal justice reforms have nearly cut the state’s parole population in half over the last decade. And a 2016 law restored the right to vote for those convicted of a felony who are serving time in county jail or in county post-release supervision programs.

Proposition 17, placed on the ballot by the state legislature this summer, is the latest move to regain the vote for those formerly incarcerated. It would join California with 17 other states that already allow parolees to vote.

Republicans in the legislature were nearly unified in opposition — arguing that disenfranchisement is a fitting punishment for the state’s remaining parole population.

“We’re dealing with murderers and rapists, not low-level offenders but utmost serious offenders,” said Senator Jim Nielsen (R-Tehama). “With the franchise to vote, they become more full participants in society — society that they’ve already shown their disdain for.”

The decision to reopen the voting rights debate to the relatively limited group of 40,000 parolees is ultimately a political compromise, said James Binnall, professor of Law, Criminology, and Criminal Justice at California State University, Long Beach.

But the conversation about voting rights in California could urge a re-examination, and not for the first time, of the premise for removing civic rights from those in the criminal justice system.

Supporters of Proposition 17 say they are not looking ahead to any larger enfranchisement push beyond California parolees. But Maine and Vermont have already gone further, and never strip voting rights for a felony conviction so that even inmates can vote.