Eyler estimates that more than 80% of Napa County’s economy is connected in some way to tourism or the wine industry.

“If people can’t find work here and other states are opening more quickly and have fewer COVID cases, have fewer fires affecting their agriculture and hospitality, people might move on,” said Eyler, who grew up in the area.

Low-wage workers facing food insecurity and the inability to pay rent will need more long-term support to hang on in the region, he said, but the pandemic and decreased tax revenues have shrunk local and state budgets.

Yalitza Garcia, another evacuee, said she lost her six-year job as a waitress at a restaurant in Yountville during the pandemic.

In June, she found another position as a server, but the restaurant — which can only seat up to 25% of its capacity indoors — lost customers as the smoky air meant patrons couldn’t sit outdoors either, she said.

“It’s really difficult,” said Garcia, the mother of two young children. “My wages have gone down a lot.”

She is one of nearly 2,000 evacuees the county of Napa has helped shelter in hotel rooms during the Glass Fire, according to county officials.

Garcia came to the evacuation center with Silvia Arroyo, her sister-in-law, to get boxed lunches for relatives staying at their hotel.

Arroyo, a house cleaner, said the fire burnt two houses in St. Helena where she worked. She had already lost clients and income during the pandemic.

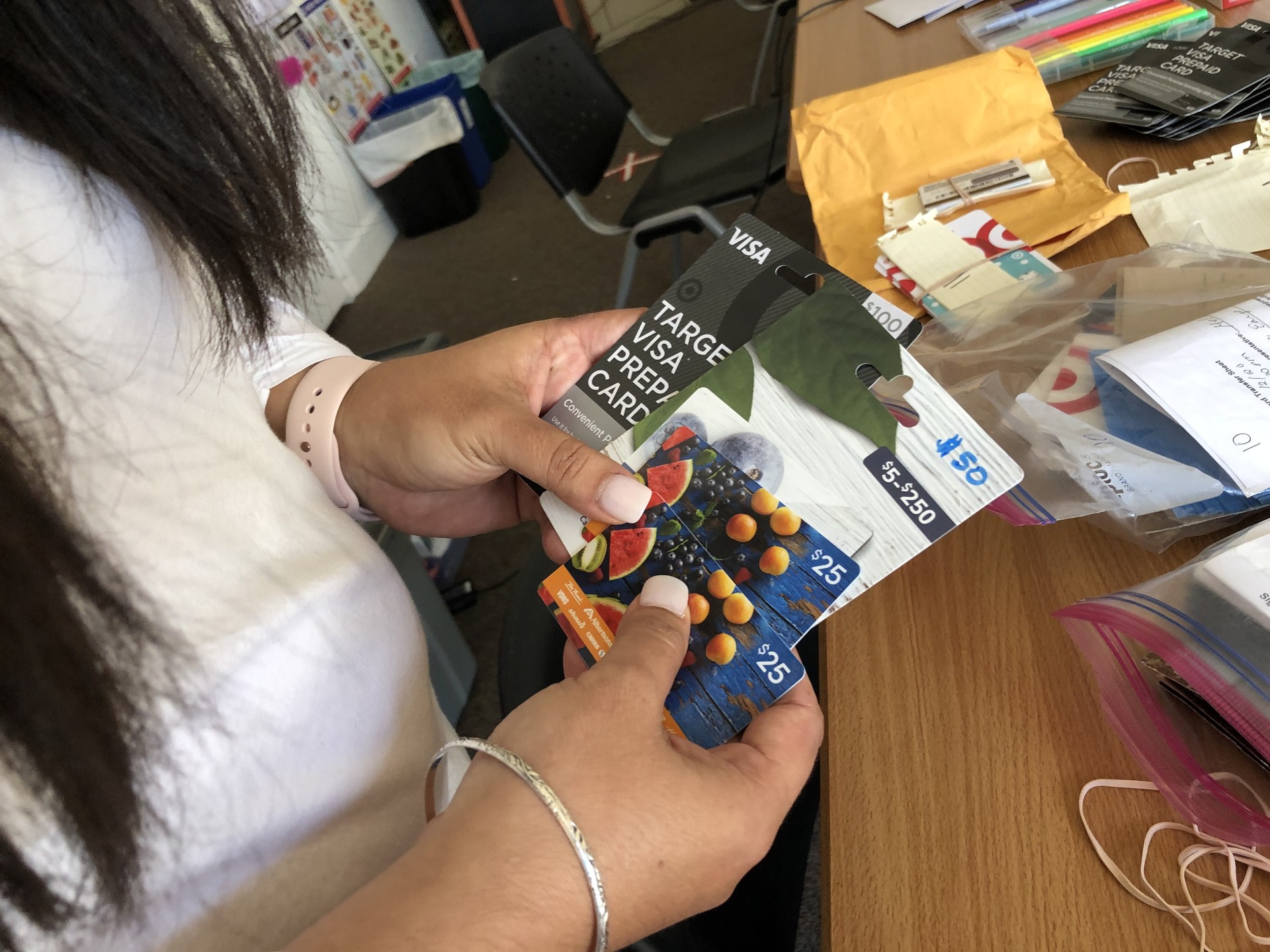

Both women said they were grateful for the immediate aid of food and hotel rooms to shelter in. But they are also applying for rental assistance from the county, which could keep their families housed until they can make more money, Garcia said.

“But we have to wait,” she said. “Because a lot of other people have also applied.”

Resources for Immigrant Workers

These organizations offer cash assistance to undocumented immigrants in wine country:

Find a full list of organizations providing assistance in Northern California here via the California Immigrant Resilience Fund.

Find COVID-19-related resources from the state of California for immigrants in Spanish, Vietnamese and other languages here.