“Rideshare drivers,” “dashers,” “taskers,” “driver partners,” “entrepreneurs,” “earners”: There’s a long list of euphemisms for low-wage service workers in the U.S. today.

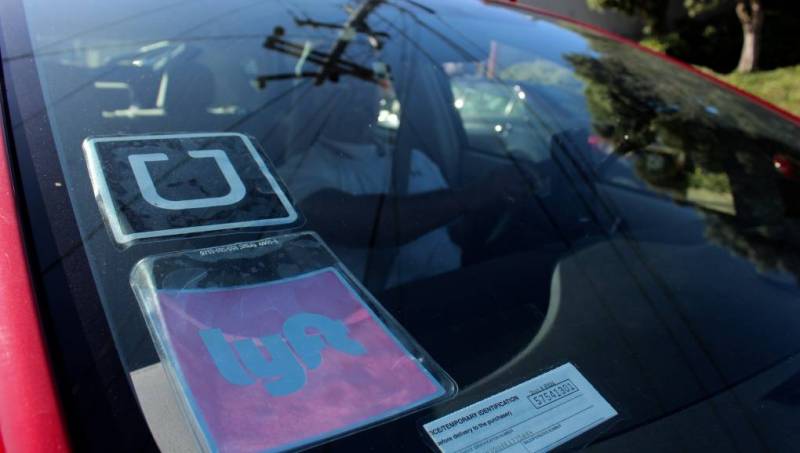

The “cute” monikers don’t just constitute a clever strategy by the public relations departments at companies like Uber and Lyft. These firms have made billions by calling their workers contractors, thereby denying them basic employee protections and benefits.

While so-called gig companies are best known for the practice these days, American companies have been making up names for low-wage workers for decades. Since the 1970s, managers and executives have created increasingly elaborate titles for workers at the same time they have weakened benefits, held wages stagnant, undermined unions and replaced full-time positions with part-time contract work. Here’s a three-hour radio documentary about how they did all that.

A long history

In 1975, Walmart CEO Sam Walton decided the people staffing his stores would henceforth be called “associates.”

Today, Subway employees are called “sandwich artists.” Taco Bell cashiers, “champions.” Amazon workers, ”Amazonians.” At Disney World, managers call everyone from the janitor to the person inside the Mickey Mouse costume a “cast member.”

“They conjure a kind of egalitarian, creative, nurturing, healthy workplace — where in almost every case in this country, what you really have is a hierarchical, routine, dull, indifferent, and more and more these days, a toxic and unhealthy workplace,” said John Patrick Leary, author of “Keywords: The New Language of Capitalism.”

Leary adds these titles aren’t just about trying to make workers feel better about their jobs, but consumers, too. The names puts a positive gloss on low-wage labor for customers who might feel guilty being served by people working jobs for little pay or satisfaction.

Leary says terms like “associate” or “sandwich artist” are so absurd they are disorienting and block critique. “It can make you feel kind of crazy sometimes,” he said. “Like, ‘Am I the only person who thinks calling the person who checks you out at Target an associate is kind of ridiculous given their place in the Target hierarchy?’ It’s part of this saturation of dishonesty and lies that you are surrounded by that can make you feel a little bit overwhelmed.”

Gig companies like Uber and DoorDash have taken the titling of workers to a new level. Almost every company comes up with a particular name for workers, and typically, the term mirrors the company name. People doing tasks for TaskRabbit are called “taskers.” People delivering food for DoorDash are called “dashers.” People gathering up and recharging e-scooters for Lime are called “juicers.”

A new economic model

Unlike the “champions” of Taco Bell, or “cast members” of Disney, executives at DoorDash, Uber and the like also claim that their workers are not employees at all, but independent business owners the company is just connecting to clients through an online platform.