This isn’t how Yosgar Godinez wanted to start the sixth grade.

Months into the school year, the 11-year-old hadn’t made new friends. He felt little connection with his teachers, and half the time he had trouble logging onto his classes, which he mostly hated anyway.

As for learning, he said he wasn’t doing much of it.

Yosgar’s mother, Francisca, worried, and so did his social worker at Oakland’s Urban Promise Academy, where Yosgar was falling further and further behind.

All of this needed to be discussed when Yosgar, Francisca and Emily Rodgers, the school social worker, met on Zoom for their first conference of the year. But while Rodgers shared the family’s concern over Yosgar’s school troubles, she does not share their native language. The Godinezes speak Mam, a Mayan tongue used by some half million people, primarily in Guatemala. The family and Rodgers both speak some Spanish, but only enough between them for the most basic communication.

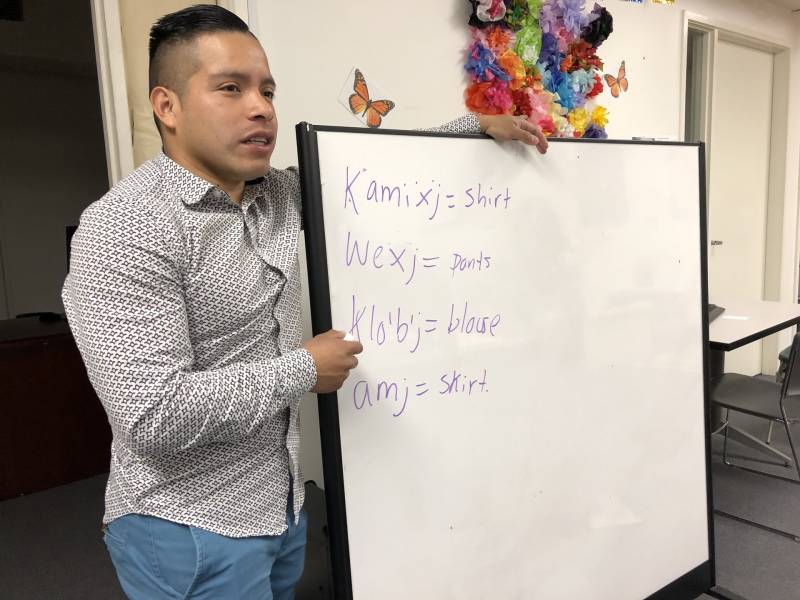

That’s where Maria Aguilar, the district’s Mam interpreter, came in.

Today, Oakland Unified School District’s support for Mayan Mam and other newcomer students is among the most robust in the country, from the creation of a continuation high school designed for recent immigrants to specialized counseling and educational programs.

But the pandemic is threatening hard-won progress. Across Oakland’s school system, a lack of computers, internet access, technological experience and practicable home learning space have forced Mam speakers to confront even more barriers to distance learning than other students are experiencing.

Coping With Remote Learning and a Language Barrier

Aguilar was, until recently, the only full-time Mam interpreter in the entire Oakland school district, where Yosgar is just one of 1,300 students who speak the language.

This school year, her calendar is a solid block of phone calls and video conferences. One hour she’s helping to set up a parent’s email account, another she’s walking a family through an unemployment application.

And one morning, earlier in the year, she facilitated a Zoom conference to discuss Yosgar’s school experience.

To break the ice, Rodgers asked Ms. Godinez to share something her son likes to do, then handed off to Aguilar to interpret. But before they could get through the first question, the Godinezes disappeared from the screen.

“Oh no!” Rodgers said. “Did we lose them?

They reconnected, but by 10 minutes in, their internet connection had already dropped five times. The group eventually abandoned Zoom in favor of a three-way phone call.

For Yosgar, it was only the latest technological hurdle since classes moved online. His mom had no computer experience at all, and because Yosgar had never used one at home before this year, he had trouble navigating the Wi-Fi hot spot and school-loaned laptop. After missing two weeks of instruction, he was finally able to connect with help from his older brother.

Such problems aren’t uncommon. District data shows schools are too often failing to reach Mam speakers during distance learning — these students are in class just 85% of the time compared with 92% and 93% for Spanish and English speakers.

Early in the school year, administrators asked Aguilar if she could help make a video tutorial in Mam, coaching families on setting up Wi-Fi hot spots. The resulting video has drawn some 160 views, but Aguilar knows that’s just a fraction of those who need the help.

Many Mam families grew up like Aguilar, without internet or computers, and some without electricity or learning how to read or write, the result of centuries of anti-indigenous racism and a decades-long civil war that devastated Mayan communities.

Today, Aguilar has found herself building tech literacy from the ground up. She spends hours on video calls trying to walk people through navigating the internet or using email for the first time.

“It’s not easy to work with parents who can’t read,” she says. “Sometimes I feel my head breaking.”

At the same time, the pandemic has school staff turning to her more than ever for help reaching parents.

“If we could clone her, I’d work with her 24/7,” Rodgers says. “Especially during distance learning, partnering with families is the only way we’re going to have success. That’s really challenging if we don’t have a way to communicate.”

Aguilar regularly works at more than 40 schools, says her boss, Nate Dunstan, who runs the district’s refugee and newcomer program. Even when Mam parents speak some Spanish, it can be hard to earn their trust over the phone, so staff often call on her.

“And then Maria starts talking to them, and everything is all of a sudden sort of fluid and familiar and clearly just much more comfortable,” Dunstan says.