A note from the KQED en Español team: In this conversation, we'll use "Latinx," "Latino" and "Latina" when referring to communities of Latin America and the Latin American diaspora. We'll use "Latinx" as as a nod toward greater inclusion of women, LGBTQ+ and nonbinary people. We've left each speaker's word choice consistent with the terms they used in this conversation.

Inspired by the outcry we heard following the 2020 elections, particularly around generalizations made by national media and politicians about who Latinx voters are, the team behind KQED en Español thought it was time for a conversation.

We wanted to bring together knowledgeable voices to talk about what the “Latino vote” is — if it exists at all — and what matters most to Latinx communities in the United States.

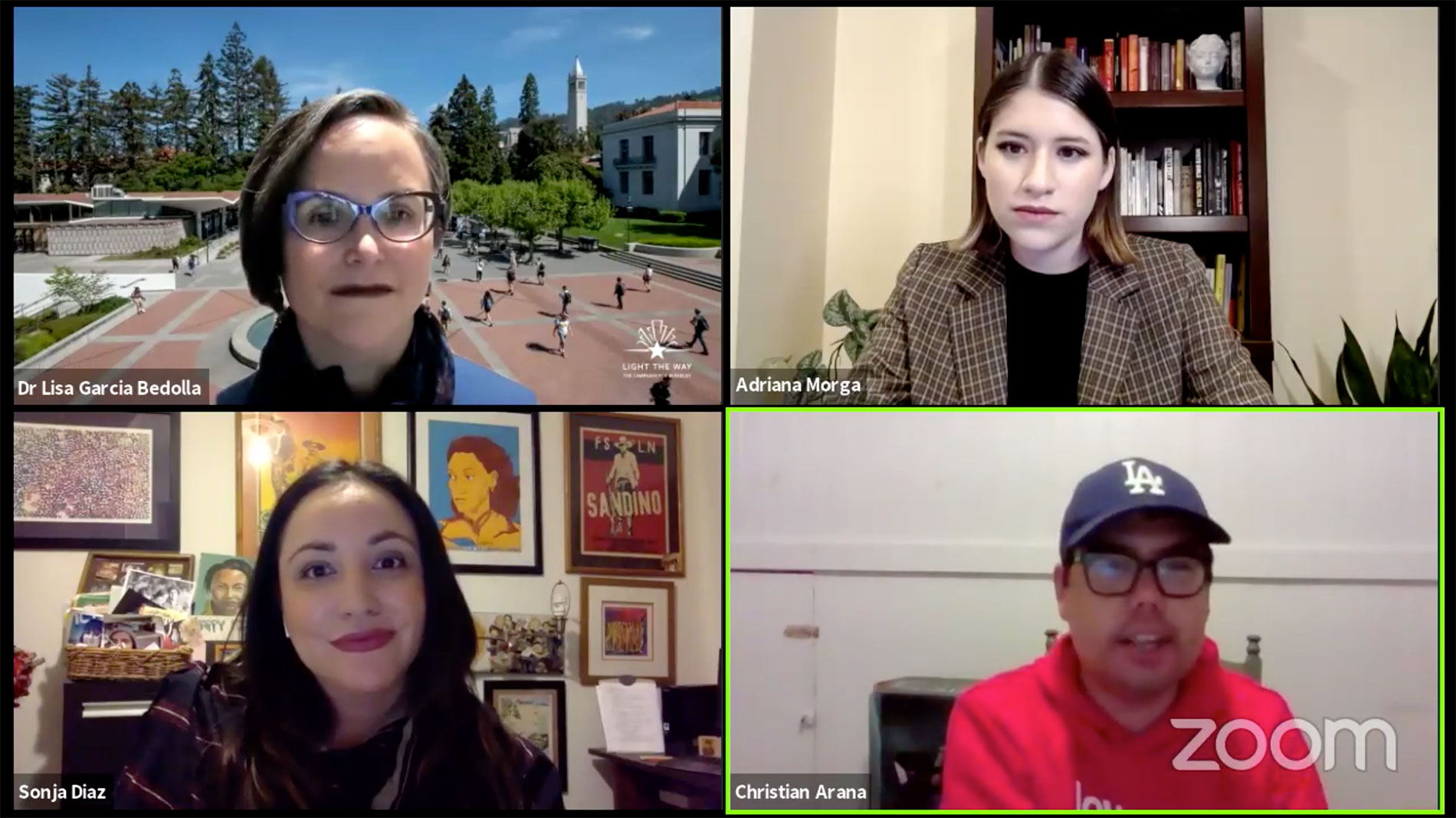

To explore the myths that the media and political pundits carry about Latinx voters and communities when it comes to election season, KQED en Español journalist Adriana Morga sat down with:

- Christian Arana, policy director from Latino Community Foundation

- Dr. Lisa García Bedolla, UC Berkeley's vice provost for graduate studies and dean of the graduate division

- Sonja Diaz, founding director of UCLA Latino Policy and Politics Initiative

Portions of this interview have been edited for length and clarity. You can listen to the full conversation here.

Adriana Morga: What comes to your mind when you hear people refer to the "Latino Vote” — if there is such a thing — during election season?

Christian Arana: Too often what we see in American politics is that there's kind of a laziness to campaigning. Back in 2008, between the election between John McCain and Barack Obama, we were all talking about this Joe the Plumber guy. And who is this guy, and what does he care about? And where does he live, and what does he think? Well, when do we ever do that for Latinos?

We're right in front of you every single day, as Latinos. But when are you ever going to stop to ask what we care about, and how you're going to win us over as voters?