Leer en español.

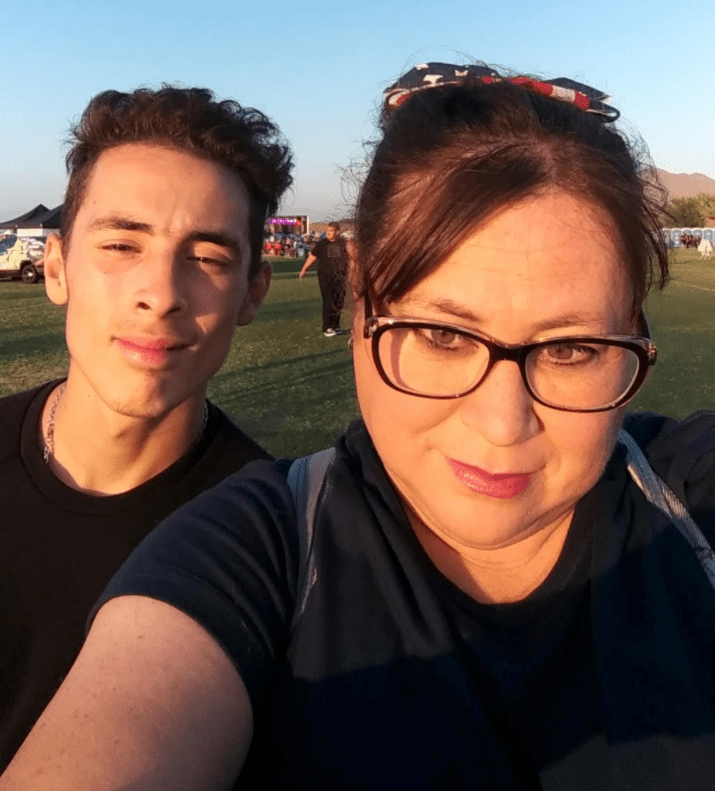

She didn’t know it at the time, but last September was when everything started to unravel for Julie Hansen. It was late in the month when the furloughed Disneyland candy maker noticed a string of suspicious charges totaling $12,222.23 on her state-issued Bank of America unemployment debit card. First, the money was credited back to her account. Then it disappeared again, setting in motion a chain of events that left her and her son homeless.

Behind the scenes, California’s Employment Development Department and longtime debit card contractor Bank of America were scrambling to rein in rampant fraud. They froze some 350,000 unemployment accounts around the time Hansen’s card was cut off.

The catch: while Hansen and other out-of-work Californians were left in financial purgatory unable to access unemployment money, a Great Recession-era contract ensured that the state and the bank kept raking in millions of dollars in merchant fees whenever debit cards still in circulation were swiped. In September, the EDD made $5.2 million on a debit card revenue sharing agreement with Bank of America — a sizable chunk of the $22.5 million the state raked in from March to October, according to public records requested by CalMatters.

How much money did Bank of America make on its end of the deal? The state says it doesn’t know, and the bank won’t say, despite a contract requirement to report unemployment debit card fees and revenue each month. “EDD does not track BofA’s revenue,” the agency told CalMatters. The bank declined to comment on its unemployment revenue and financial reporting.

“This is essentially a nifty little hidden kickback scheme,” said Assembly Member Jim Patterson, a Republican from Fresno. “This is becoming far too familiar. EDD just does not tell us what’s going on.”

Basic Questions Unanswered

In recent weeks, California lawmakers rushing to introduce new unemployment reform bills have struggled to get basic questions answered about when and how jobless workers are paid — and who profits in the process.

Under Bank of America’s exclusive 2010 unemployment debit card contract with the state, which was first detailed by CalMatters, the Employment Development Department does not pay the bank directly for its financial services. Instead, the two parties split revenue on merchant transaction fees when the cards are swiped, and the bank charges limited consumer fees for things like ATM use or rush shipping on new debit cards. The contract specifies only that the state’s share of the fee revenue will “assist in offsetting program costs.”

The bank was supposed to report at least monthly on any fees earned and its average revenue, according to the contract provided by the state. But when CalMatters asked for those reports, the state said it did not have any records on bank fees. The agency said only that Bank of America made $37.8 million in transaction fees during 2013 — a figure disclosed as part of a bond estimate in a year when California paid out a sliver of the record $111 billion in unemployment benefits from March to December last year.