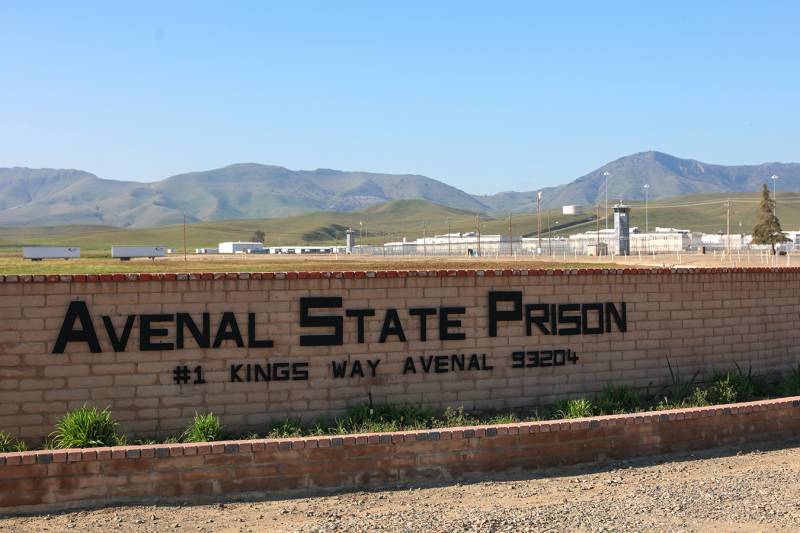

When news of the pandemic first reached the men incarcerated at Avenal State Prison in Central California, inmate Ed Welker said the prevailing mood was panic. “We were like, ‘Yeah, it’s going to come in here and it’s going to spread like wildfire and we’re all going to get it,’ ” he said. “And that’s exactly what happened.”

Almost a year later, 94% of Avenal’s incarcerated men have contracted COVID-19 and eight have died. With more than 3,600 confirmed cases among prisoners and staff members, the facility tops the list of the country’s largest COVID-19 clusters in prisons compiled by The New York Times and the UCLA COVID-19 Behind Bars Data Project.

Calling the prison system’s response to the pandemic “nonchalant,” “incompetent” and at times “negligent,” Welker and his fellow inmates described a crowded and dangerous living situation. Inmates interviewed by Valley Public Radio said physical distancing was nearly impossible, and constant moves in and out of quarantine were confusing and disruptive. The postponement of visits and rehabilitative programs left the men with little opportunity to vent their frustrations.

“It’s chaos over here, man,” said John Walker, 50, an inmate interviewed via the prison system’s collect-calling service during the fall surge in cases. “That’s why the mental health program’s blowing up.”

Similar grievances have been voiced by prisoners across the country, who have contracted the virus at a rate more than three times that of the general population, according to an analysis by The Associated Press and The Marshall Project, a nonprofit newsroom dedicated to the U.S. criminal justice system. Lawsuits and criminal justice advocates detail a pandemic response in prisons and jails that has ranged from careless to egregious.

California’s prison authority denies many of these men’s claims and instead points to the long list of precautions the agency has adopted since the pandemic began. Dana Simas, press secretary at the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, wrote in an email that state and Avenal officials “are continuously working with public health and health care experts to address this unprecedented pandemic and protect those who live and work in our state prisons.”

The virus continues to devastate prison populations and employees. Despite a dramatic drop in new infections since the holidays, more than 15,000 inmates nationwide have contracted the virus in the past three weeks, according to The Marshall Project. California’s facilities serve as a case study in which outbreaks recur while prison advocates argue that officials failed to enact a critical precaution: relieving overcrowding.

“There has not been the political will to do what’s necessary to keep people safe, which is to dramatically reduce prison and jail populations,” said Aaron Littman, a teaching fellow at UCLA School of Law and deputy director of the COVID-19 Behind Bars Data Project.

Early in the pandemic, corrections agencies across the country put in place measures to prevent outbreaks, mandating masks and physical distancing, setting aside housing units specifically for quarantined inmates, and establishing testing protocols for staffers and the incarcerated.

“The measures are important, the measures help … but those are not sufficient,” said Littman.

Horrific errors occurred. In late May, for instance, a transfer of a handful of inmates later discovered to have been COVID-positive sparked an outbreak that killed 29 people and infected 2,600 others at San Quentin State Prison in Northern California.