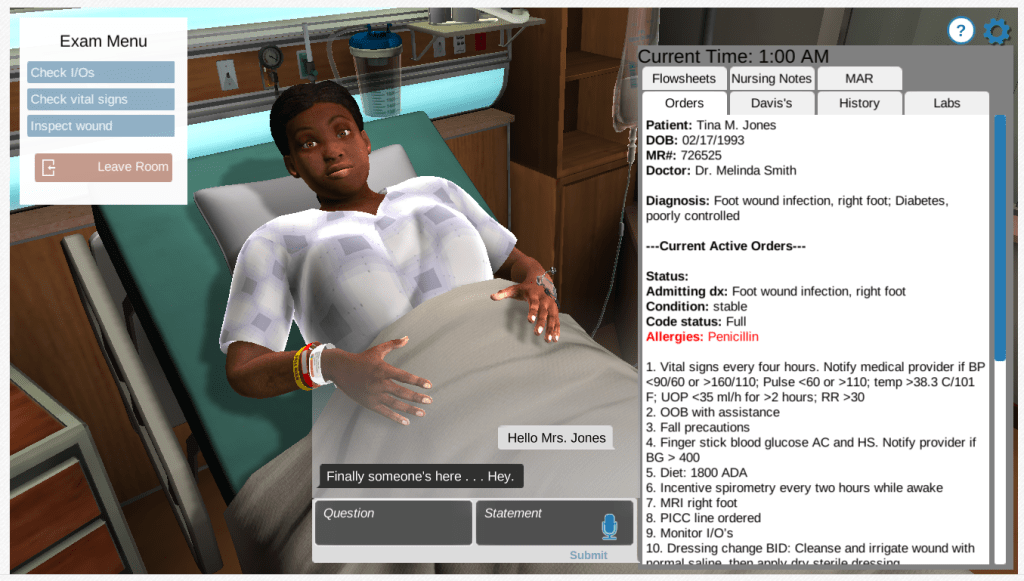

Dressed in a white gown and hooked to an IV pump, Tina Jones was sitting on a hospital bed when nursing student Erin Abille greeted her.

Glancing at Jones’ chart, Abille saw that the patient came into the hospital for a foot infection and had a penicillin allergy.

“Are you in any pain?” Abille asked.

“Oh, OK,” Jones responded.

The bizarre response wasn’t the only unusual thing, Abille noted. The patient also had stilted facial and hand movements.

But those symptoms weren’t due to a medical condition — they were because Jones is not a real patient but a computer avatar in Shadow Health, a virtual simulation that has been widely adopted by nursing education programs across California since the start of the coronavirus pandemic.

The pandemic has restricted the number of clinical placements available to nursing students in hospitals, forcing them to practice their skills instead on mannequins, virtual patients like Jones, or at home with relatives and even stuffed animals.

California has relaxed regulations to allow for more virtual education, but some nursing students say they feel less confident in their skills, and others have had their graduation delayed, at a time when the state arguably needs nurses more than ever.

Hospitals have been reluctant to place nursing students at risk by having them enter a workplace filled with COVID patients, and more experienced nurses have been too busy with patient care to supervise them, said Loretta Melby, president of the California Board of Registered Nursing, a state agency that regulates nursing education.

“It was really difficult for all of our students when the facilities that they’ve relied on for years to do their clinical practice said, ‘We can’t have you here anymore,’ ” she said.

What Practicing at Home Means

Prior to the pandemic, nursing students were required to spend at least 75% of their clinical time providing direct care to patients in hospitals. The Board of Registered Nursing relaxed its regulations in April 2020 to allow students to fulfill half of their clinical hours in simulated scenarios, but said it will reverse that decision when the pandemic is over.

For Abille, that means that instead of checking her patients’ vital signs with her stethoscope and thermometer, she now relies on the electronic health records shown at the bottom of her laptop screen.

Caring for faux-patient Jones, she said, is a stark contrast to the close relationships she developed with patients when working as a certified nursing assistant at a skilled nursing facility. There, she had emotional conversations with elderly patients on the geriatrics floor, many of whom were reflecting on the choices they’d made in life as they neared its end.

Abille wasn’t able to do that with Jones. “I couldn’t pry into her personal life, I couldn’t pry into her worries, I couldn’t pry even into her pain,” she said.

Before the pandemic, Abille would have received one-on-one mentorship from a senior nurse on how to do sensitive procedures, such as inserting a catheter into a patient’s urethra. Now, with her college’s skills lab closed and even mannequins unavailable, she practices at home. A unicorn Pillow Pet stands in as her patient and she uses a water bottle to replicate the urethra.

Abille said she worries that she might accidentally reinforce mistakes because she doesn’t have her instructor to immediately correct her. Having a catheter inserted is a scary procedure for many patients, who often wonder whether the procedure will hurt. That’s not a conversation she can have with her unicorn.

In person, nursing students can use all of their senses when caring for patients, but with simulations, they miss out on the physical cues that patients give to signify pain or discomfort, said Melby of the BRN.

“When I worked in the ICU, I could smell various things like a gastrointestinal bleed,” she said. In a simulation, “you’re not getting that kind of input. Your mannequin can’t grimace.”

‘A Real-Life Situation in a Non-Threatening Environment’

Despite the drawbacks, virtual simulations do have some upsides, said KT Waxman, director of the California Simulation Alliance at HealthImpact, a nonprofit focused on health workforce development.

Students can still develop their critical thinking and clinical judgement. When instructors create clinical scenarios over Zoom or show a video of a heart failure, debriefing allows students to grow more confident in their ability to handle those situations, Waxman said.

“You expose the students to a real-life situation in a non-threatening environment, where students know if they make a mistake that the life of the patient is not at stake,” said Salima Allahbachayo, director of the nursing program at Citrus College, which has relied on computer simulation to continue teaching during the pandemic.

She says her students were able to learn more through Zoom scenarios because repetition allows them to correct their mistakes.

Besides spurring a move toward more simulation, the pandemic has shrunk the number of available slots in colleges’ nursing programs, said Joanne Spetz, director of the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies at UCSF.

Some nursing programs in California didn’t admit any new students this year, at a time when the state is projected to have a shortage of 44,500 full-time registered nurses by 2030, according to the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. And around one in 10 nursing programs in California has suspended admissions for 2021-2022, according to preliminary data from a survey Spetz is conducting.

“For those students, that’s another semester or quarter where they’re not able to get started,” said Spetz. “It slows down their graduation, and overall slows down the supply of nurses into our workforce.”