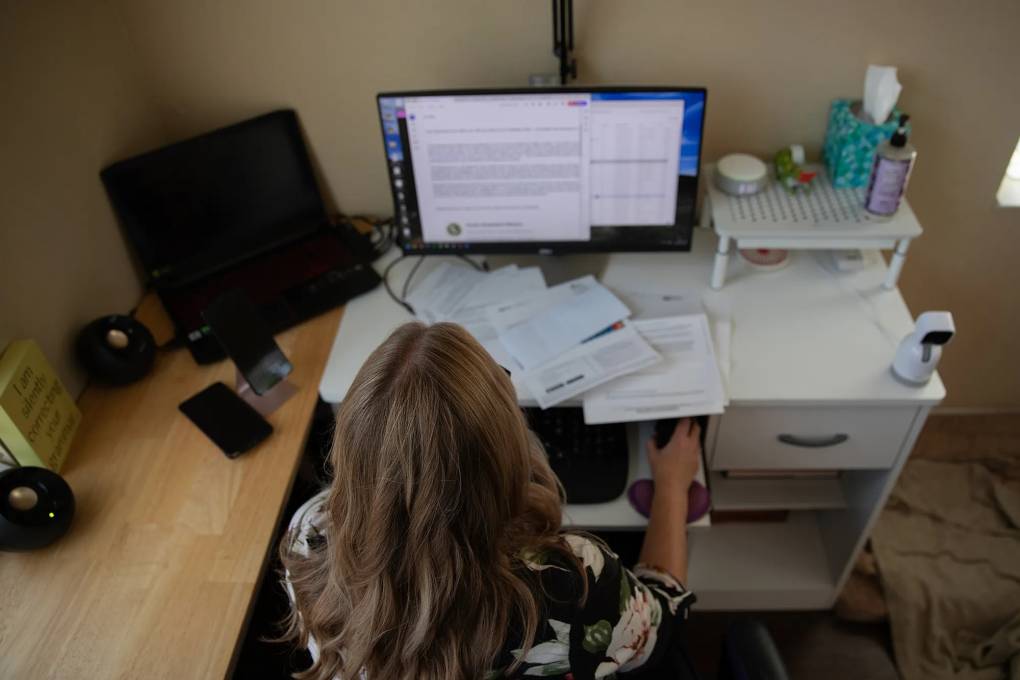

And then came the virus. Lira’s memory is still a blur, but her lungs seized up, and she was frantic that no one would be able to figure out the unemployment money or keep food in the cabinets if she was gone. Finally, after a week in the hospital, Lira has mostly recovered.

“That day in there at the hospital,” she said, “I almost wanted COVID to take over.”

Behind the scenes at EDD, a very different scramble has been playing out in response to millions of calls each month from claimants like Lira. In April, Deloitte signed an $11 million emergency call center contract; the department said that “staff cannot keep up.” By early 2021, the contract had grown to $55 million, plus another $14 million for “urgent and temporary” IT services from Deloitte.

Maximus is providing another 300 call center staffers for tax questions under an $11.5 million contract, according to the department.

In addition, a new crop of tech vendors has been brought in to augment the state’s old computer systems and beef up cybersecurity.

In April 2020, the unemployment agency started buying Salesforce software from the firm Outreach Solutions As A Service, to help with the bottleneck of claims. The cost started at $2.7 million and more than tripled by November.

Meanwhile ID.me was hired in September, via an IT firm called V3Gate, for its “robust and established identity verification” services in a $3.5 million contract, which nearly tripled by January.

Thomson Reuters, which acquired an analytics tool called Pondera previously used by the state, was hired in November for $771,000 worth of identification and fraud analytics work. That contract grew more than five-fold by January.

To Jon Coss of Thomson Reuters, the spike in contract spending was unavoidable, due to a combustible mix of historic underfunding of unemployment programs, the federal easing of verification requirements on emergency jobless aid during the pandemic and an avalanche of increasingly sophisticated fraud.

“It was an impossible situation,” Coss said. “States have been passed, and they’re outgunned by these fraud networks now. I just don’t think it’s possible to do it purely with staffing.”

Coss, vice president of risk, fraud and compliance in Thomson Reuters’ government division, also argues that it’s better for the state long term to contract out technical work during emergencies, rather than hiring new full-time workers whose positions may not be necessary when there are fewer jobless claims.

While some contracts went through a competitive bidding process, others did not. Now, as the unemployment debacle fuels the campaign to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom, it’s colliding with bigger questions about how the state has doled out money during the COVID-19 crisis.

California has also signed hundreds of millions of dollars worth of public health contracts with UnitedHealth and other large Newsom political donors, some through no-bid or expedited emergency processes. “There is no time to do competitive bidding given the urgent need,” Krista Canellakis, deputy secretary for general services at the state Government Operations Agency, recently told CapRadio.

Technical Problems Persist

Underlying the race to answer clogged phone lines and sort out delayed payments is the EDD’s long-problematic tech backbone.

The computer system that California uses to track unemployment claims isn’t just old. It’s a relic of the post-World War II era, when COBOL was the world’s default programming language.

Last fall, as the department nearly came unglued amid mass account freezes and panic about fraud, Newsom said the agency’s 30-year-old system needed to be “strewn to the waste bin of history.”