On Monday, the Oakland Unified School District will welcome back third through sixth graders at select schools. But as kids prepare a gradual return to in-person learning, some parents are still feeling hesitant about ending distance learning altogether.

Ryan Austin, artist educator and Oakland resident, said she's seen the wide range of effects that distance learning can have on kids, in part based on the kind of support systems they have at home.

Austin’s sister, Arayna, is an OUSD sixth grader. She attends all her classes through Zoom and does her best to keep up with schoolwork. But Austin said it’s difficult for her to engage with the material and her classmates.

“She’s not very present,” Austin said. “I’m witnessing a dearth of her education experience.”

But Austin's 6-year-old son, Onyx, who attends a private school in the city, has been thriving during his remote classes. That's in part because Austin and her husband, Michael, work from home, she said, and they’ve been able to spend a lot of time together with Onyx to work with him to understand what his learning styles and interests are.

“We’ve hit our stride. He’s learned the expectations about how his day goes, he’s fallen into a rhythm,” Austin said. When she is able to, she sometimes audits Onyx’s classes to learn how her son is adjusting to distance learning and jots down what he needs extra help with.

Staying at home has also helped boost Onyx’s health. When he entered kindergarten last school year, he had to miss 11 days of school after coming down with a heavy cold. This especially worried his parents because Onyx has serious allergies.

This school year, Onyx has not missed a single day of school.

“As a family, we’ve maintained that it’s best for him to keep learning here at home,” Austin said. “We just want to make sure that there are better safety protocols before we put him back into a space where we know he will be exposed to all kinds of illnesses, namely COVID-19.”

Despite the fact that Onyx is allowed to return to in-person classes, Austin said she's keeping him home for now.

Why? Because Austin and her husband can be at home throughout the day to provide him support.

“We’re aware that we have a privilege that we’re able to be here with him, that other people don’t have,” Austin pointed out, “so I wouldn’t dare to tell other folks to not take their kids to school.”

Other parents she knows are front-line workers who don’t have the option to stay home with their kids. Having schools reopen allowed them to drop off their kids and head to work knowing that they won’t be alone in the house.

As districts across California have grappled with difficult conversations around reopening, Austin said she's been troubled by a certain aspect of the school reopening conversation: Organizations and advocates — both for and against reopening the Bay Area’s schools — have both cited the needs and experiences of Black and brown parents to support their viewpoints.

“Going back to school, the narrative that is out there for Black and brown folks doesn’t necessarily represent everybody,” she said. “We’re not a monolith.”

Austin feels that those pushing to delay or speed reopening should be talking less about Black and brown parents, and should be spending more time talking with them.

For Parents of Color, Mixed Data and Mixed Experiences

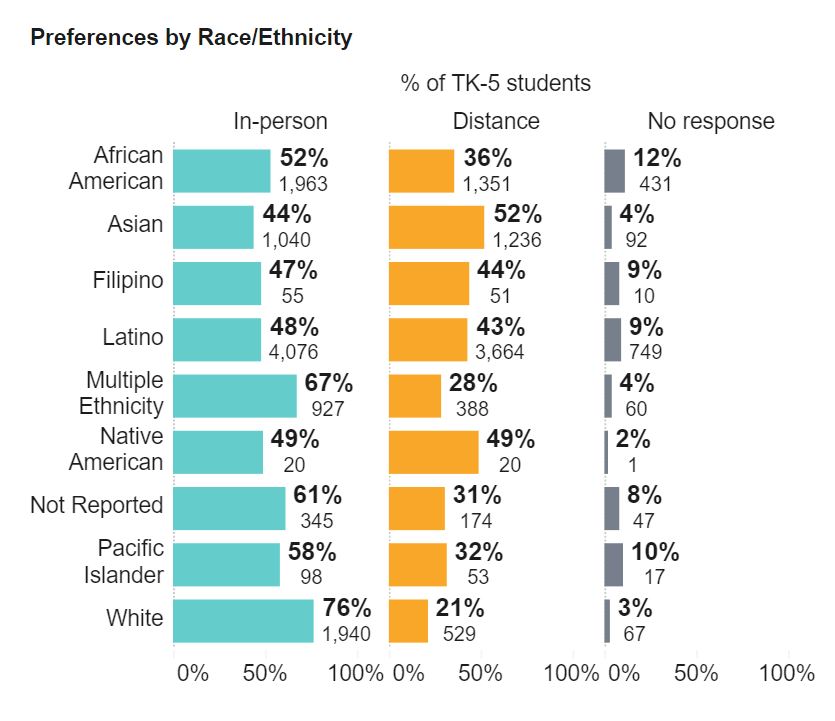

In March, OUSD released the results of the form it sent out to parents of kids in transitional kindergarten through fifth grade. The choice the district offered parents was simple: a return in-person, at least part-time, or remaining in distance learning for the remainder of the school year.

Parents of white students are the group with the highest preference for in-person learning at 76%, while 21% chose distance learning.

But results are more mixed among Black and Latino families.

Of the Black parents surveyed, 52% said they favored in-person learning, while 36% chose to continue distance learning. With Latino students, the margin is even smaller: 52% of parents selected in-person and 48% went with distance learning.

Among parents of Native American students, both options tied at 49%, while slightly more than a majority, 52%, of Asian families preferred to continue distance learning.

While the survey shows a majority of white families are in support of returning to in-person learning, the situation isn't as clear cut for families of color. And the small margins between the numbers suggest that race is not the best indicator of what those families might do in regards to school reopening.

Fruitvale resident Antonio Escobar is the parent of two kids. He said he felt relief when he heard schools were reopening.

Having his first grader and pre-kindergarten student home all the time has been extremely difficult for him and his wife. Because they both have jobs outside the house, they’ve had to coordinate a system during the pandemic so that one parent is always home.

“When the kids are in the house, they just want to play. If they go into class, they don’t learn much because they are so distracted,” he said in Spanish.

If the kids need help with their classes, Escobar is not always sure how to help them. His biggest concern is that they’re not learning what they need to, and his family doesn’t have the time or the resources to provide extra academic support.

“It’s going to be so much better as the kids go back to school because there they can actually focus and do their schoolwork,” he explained.

On the other hand, Claudia Guzmán, also a Fruitvale resident, decided her first grader, Alexis, would continue distance learning.

“When they go in, they will need to have the mask on the whole day, wash their hands every so often and keep social distance. So I think it will be difficult for him to keep his facemask on all day and just take it off to eat,” Guzmán said.

She’s a stay-at-home mom which, as she points out, allows her to assist Alexis with any bumps in the road, like bad Wi-Fi or a new lesson. “So being at home seems better to me even though I know he's not concentrating as much as he should be,” Claudia adds.