With a piece of bread, Roberto González, Mariana Mejía and Kaled Escobedo Vega broke their hunger strike on Wednesday afternoon, standing victoriously in front of San Jose City Hall.

They hadn’t eaten since early Monday morning.

With a piece of bread, Roberto González, Mariana Mejía and Kaled Escobedo Vega broke their hunger strike on Wednesday afternoon, standing victoriously in front of San Jose City Hall.

They hadn’t eaten since early Monday morning.

“¡Sí se pudo! ¡Sí se puede!” they cheered as they chewed their first bites.

The celebratory breaking of bread came after the San Jose City Council on Wednesday agreed to a weeklong postponement of a vote on whether to allow the rezoning of a 60-acre site in the northern part of the city where a storied, sprawling outdoor flea market has operated for more than 70 years.

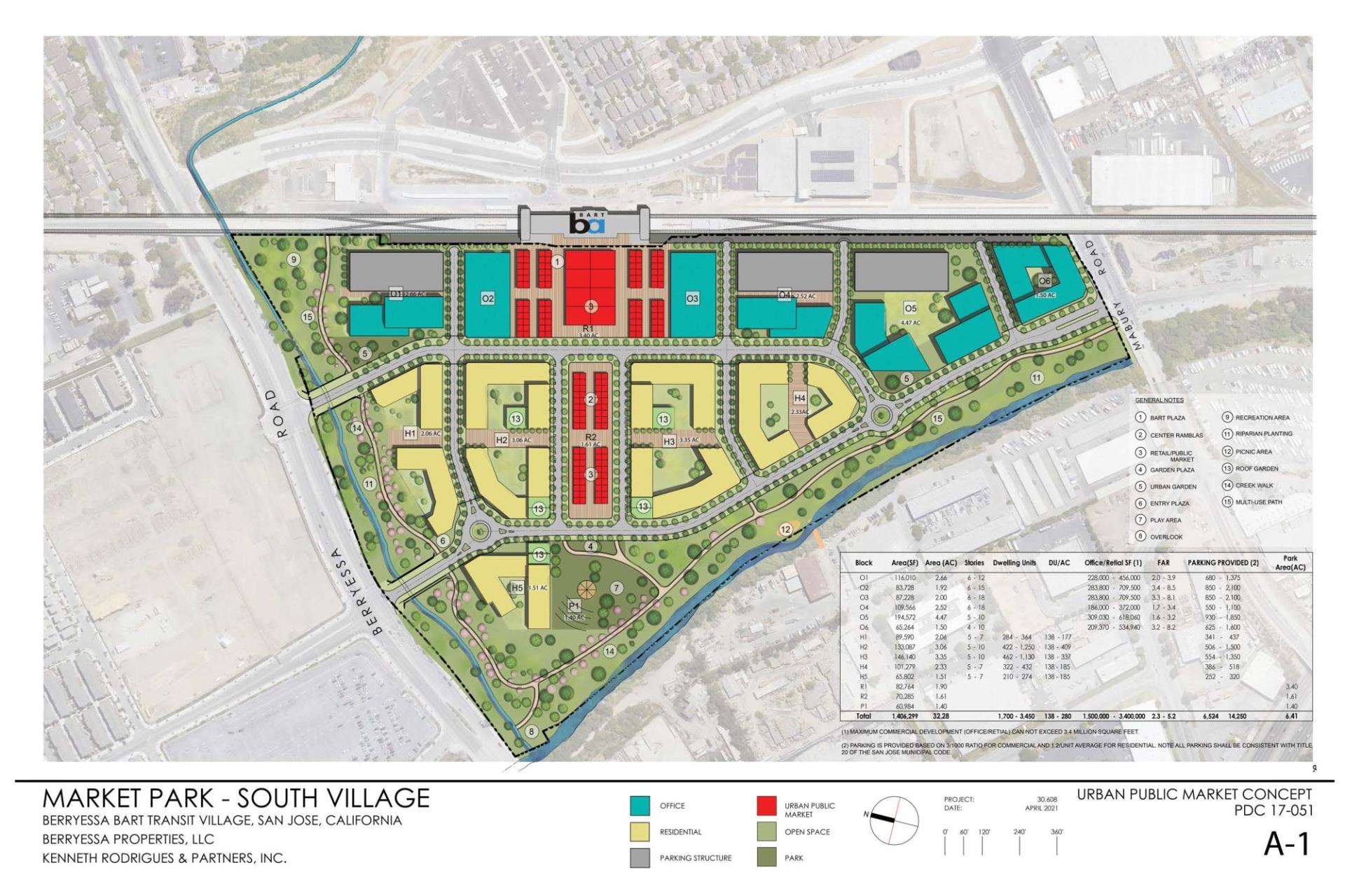

Hundreds of small businesses run stalls at the San Jose Flea Market, or La Pulga, as it’s known in Spanish. But the proposed development, dubbed the Berryessa BART Urban Village, which would be built next to the city’s new and only BART station, would radically alter the property — and the market — to make way for more than 3 million square feet of office and retail space, and some 3,400 housing units.

The hunger strike was organized by the Berryessa Flea Market Vendors Association (BFVA), a group created late last year in opposition to the proposed development. While its leaders initially demanded the vote be delayed by 90 days, González, the group’s president and a vendor at the market, said the extra week is enough time to reach a new deal.

“This was a great victory for us today,” he said. “The struggle is not over. We will continue on till we find those securities and those assurances for every single vendor and for all of our small businesses.”

The landowners’ proposal includes a concession of five acres for a new “urban market” set aside for La Pulga vendors. But that would shrink the flea market to less than a third of its current size, falling far short of accommodating the majority of its vendors. And the construction process alone could displace vendors for years.

While the Bumb family, which has owned the land for generations, offered $2 million earlier this month toward a fund to support vendors if the rezoning plan is approved, vendors point out that once this amount is divided among hundreds of business owners and their employees, each person would receive about $4,000 — not nearly enough to make it through multiple months without any additional income.

“We let the city know that these plans were insufficient for the most part,” González explained. “We need direct involvement with the community and with the vendors to find a good solution to this issue.”

The BFVA later responded with its own set of demands, including five-year leases for all vendors and $2 million for an extensive third-party analysis to determine how the market could sustainably operate in the future and where it could potentially relocate.

But at Wednesday’s council meeting, Erik Schoennauer, a land-use consultant who represents the Bumb family, warned council members that if they delayed the vote, his clients would take everything they’re currently offering off the table.

“Either approve the urban village plan and the new project that is before you or we move forward and develop the project that’s already approved,” Schoennauer told councilmembers, referring to a previous rezoning plan authorized in 2007 that includes no vendor space or affordable housing units.

“Any delay, any denial, and we simply build [that] project,” he added.

Although some city leaders, including Mayor Sam Liccardo, have signaled the city has too much to lose if the Bumb family pulls out on its current proposal, others aren’t buying the threat.

“I think it’s absolutely posturing,” said Councilmember Raul Peralez after voting Wednesday in favor of the continuance. “I don’t think they’re going to walk away at all. There’s a lot at stake for them as well and I think we will come to an agreement next week.”

On a recent day at La Pulga, rows of piñatas hang over the entrance to Ana Vázquez’s stall, gently greeting visitors with a tap on their heads. She carefully sets down a clay pot, painted and glazed with leaves, flowers and geometric designs, next to a jar full of almond-powder candy.

For more than 30 years, Vázquez has taken care of her stall, one of the roughly 750 that make up the the flea market, among the biggest swap meets in California.

“People from all over come to find goods here, like clay jugs or candy,” Vázquez said in Spanish, noting that many of the items in her stall can only be found in Mexico and Central America.

“I have clients who send dulce de leche all the way to their children who now live in New York,” she said, referring to the popular Latin American dessert made of sweetened condensed milk. “This is something I’m proud of. It makes me proud when I hear folks say, ‘Let’s go to the tiendita.’ ”

La Pulga first opened up in 1960, when farms crisscrossed the northern part of the city. La Pulga, as the market is also known in Spanish, had plenty of space to expand.

But northern San Jose is no longer the agricultural area it once was.

Urban villages and condominium developments have popped up where orchards once stood. Almost every 15 minutes, BART trains roll into the Berryessa/North San Jose station, which opened up in June 2020. The arrival of BART into the city seemed to mark a new chapter in San Jose’s transformation into a major metropolitan hub.

For a while now, Vázquez has feared that the flea market would be surrounded, and eventually replaced, by luxury condominium developments, pushing out hundreds of businesses.

“Our only income comes from here,” said Vazquez, pointing to her stall. “At our age, it’s not easy finding a new job. It will be really difficult to get through this, for me and for so many others that depend on the flea market.”

Chau Nguyen, 70, has sold luggage and handbags at her stall at La Pulga since 1993, starting the business just a few months after arriving in the U.S. from Vietnam. If the flea market closes during construction of the new development, or if her stall isn’t included in the proposed smaller market, she doesn’t know what she’ll do to make ends meet.

“It’s my job,” she said. “Even though I’m over 70 years old … I still like to work.”

Nguyen doesn’t receive Social Security benefits, so whatever she earns from her business is what keeps her and husband afloat. She also has family still in Vietnam that she tries to send money to when she can.

La Pulga vendors have formed networks across the Bay Area of suppliers and other small businesses who depend on the flea market, even if they don’t work there themselves.

Mario Davila, 50, loves soccer, perhaps as much as he loves being at La Pulga. He’s worked there for 21 years, and for him, it’s irreplaceable. “We want people to come and spend their Sunday here, for them to find food, have fun,” he said.

Davila supports his family in Peru with his earnings, and for him, like other vendors at the market, the stakes of the pending land-use decision are high. “It’s not easy finding a job outside,” he said. “We’re not a burden to anyone.”

Cayetano Araújo, 65, who sells dry fruits, peanuts and other snacks at La Pulga, says that if his business doesn’t survive the market’s transformation, it will be more than just his family who are impacted.

“Behind me there are my suppliers. Those are three different families,” he said in Spanish.

“We are not opposed to [the developers’] plans but we’re against not being included in the plans,” he added, contending that the perspective of vendors has never really been taken into consideration during the years-long process.

Even if all the vendors can squeeze inside the proposed smaller market space, Araújo says it would change the essence of La Pulga, a place where visitors are encouraged to move around freely through the massive market.

“So many families come to stroll around with their kids. This is a flea market for relaxing and moving around, amusement, strolling around, enjoying a snack, a beverage, all of that,” he said. “This tradition of 80 or so years would be lost in one moment.”

But the sprawl exemplified by La Pulga and the surrounding area has increasingly fallen out of favor with San Jose officials.

In 2011, the city adopted its master plan, Envision San Jose 2040, that encourages the development of higher-density, mixed-use urban villages built near transportation sites, with the goal of reducing traffic congestion and carbon emissions and increasing housing supply near the city center.

The plan prioritizes development in northern San Jose, specifically the Berryessa area, where the new BART station was built.

“Having a transit hub at the end-of-the-line BART station … getting a dense urban village there is important,” said David Cohen, a San Jose city councilmember for District 4, which includes the area in question. He voted against Wednesday’s continuance.

“Building transit-oriented development is the only way that we can sustain our Bay Area environment for the future,” Cohen said.

Vignesh Swaminathan, a South Bay native and civil engineer who heads Crossroad Labs, a consulting firm, says San Jose has to choose between fully embracing transit-oriented development or seeing the city continue to sprawl.

“Already in San Jose, people are driving two to four hours just to get to work because of financial displacement,” he said.

“If we don’t build densely and decide that we’re going to build a development a few blocks away [from the BART station], then that extra 10-15 minutes to walk from the BART station to that development will be the decision factor for someone not to take BART,” Swaminathan said.

But he acknowledges that while these strategies are meant to reduce congestion and sprawl, they may also inadvertently end up hurting some residents and businesses.

“That’s why the flea market is such a complex issue,” he said. “It’s following all the best practices that the city and agencies have been trying to do to try and plan properly. But for the folks who are trying to fight gentrification, fight displacement and accommodate culture, it’s not enough for what we need.”

To learn more about how we use your information, please read our privacy policy.