Corrections: We adjusted our overall number of evictions after removing 6 duplicate records and 5 evictions at commercial properties.

As California’s eviction protections neared their expiration on June 30 and concern rose about a wave of evictions, the governor signed legislation this week to extend the moratorium, allowing more time to get relief into the hands of struggling renters and landlords.

But even as the state and local moratoriums have been in place during the pandemic, more than 1,000 Bay Area residents were evicted from their homes, according to an analysis of public records from sheriff’s offices in nine counties.

The data includes only instances when sheriff’s deputies were called to physically remove someone from their home, which experts say represents only a small fraction of total evictions.

But the data — compiled and analyzed by KQED and researchers at UC Berkeley’s Urban Displacement Project — provides insight into where those evictions are happening, who is most vulnerable and the effectiveness of tenant protections.

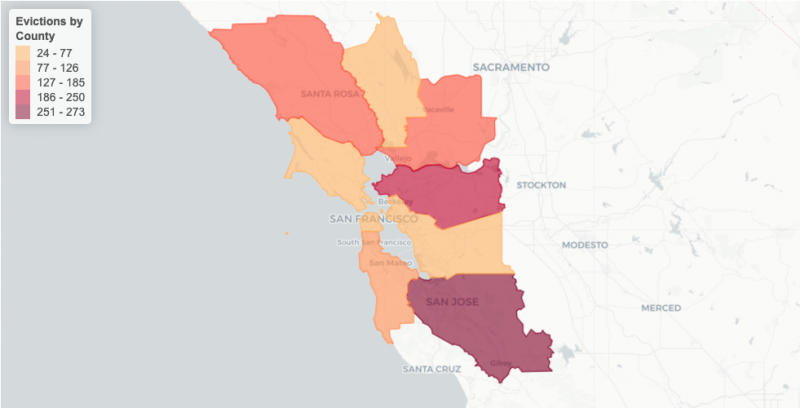

See Where People Were Evicted in the Bay AreaClick on the map below to see how many people were evicted from March 19, 2020 to March 31, 2021 by county, city or census tract. |

Roughly half of the 1,012 lockouts occurred in two counties, with 270 in Santa Clara County and 227 in Contra Costa County. Comparatively, in Alameda County, which has half a million more residents than in Contra Costa, sheriff’s deputies performed 25 lockouts, the lowest of all nine counties.

The disparity is largely due to differences in protections for tenants that county and city officials enacted during the pandemic, said Anne Tamiko Omura, the executive director of the Eviction Defense Center. The legal services organization counsels tenants in Alameda County and parts of Contra Costa County.

“It quantifies what we experience day in and day out,” she said, “which is the huge disparity between tenants who live in Alameda and Contra Costa counties.”

Alameda County allows only evictions for health and safety violations or if a landlord is taking their property off the rental market, Tamiko Omura said, making its moratorium one of the strongest in the state. By contrast, Contra Costa’s tenant protections are more narrowly focused on blocking evictions for nonpayment of rent. It allows other evictions, including, for instance, breaches of the lease or nuisance allegations.

The same is true in Santa Clara County, said Caryn Hreha, a staff attorney at the Law Foundation of Silicon Valley. Hreha said her office now mostly sees nuisance claims as the grounds cited for an eviction, in part because it’s one of the few ways landlords can evict tenants.

“We have cases where it’s the sound of running and jumping from children because it happens frequently, backyards that aren’t cleaned up, parking disputes over who is parking in what spots,” Hreha said. “Those are things landlords are calling nuisances, and those are the cases that are going forward.”

The data also points to racial disparities in evictions, said Tim Thomas, research director at UC Berkeley’s Urban Displacement Project. He estimates that Black renters were twice as likely to be evicted than white renters, a finding that is in keeping with national studies.

The data does not include racial demographic information for the people who were evicted. But Thomas and graduate student Alex Ramiller used an algorithm that combines last names with neighborhood demographic information and applied it to 658 eviction records to predict the race of an individual evicted.

Tenants who were evicted were also more likely to be living in neighborhoods that have higher poverty rates, lower median rents and have slightly higher levels of rent burden — meaning renters pay more than a third of their income toward rent.