The Bay’s how-to newsletter series is an extension of By the People episodes that look into how democracy functions in the spaces around us — and where, exactly, each of us can plug in. These features include changemakers who have learned how to get involved locally and who are now sharing their step-by-step guides with you.

Protest and policy can work together. Protests may raise awareness and understanding about issues and affect legislation — such as the 2016 protests against the Keystone XL Pipeline in North Dakota that threatened sacred Native American sites and burial grounds and risked polluting a major water source for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. The added pressure from protests led to President Joe Biden canceling permits for the controversial project on his first day in office. Last year’s protests around George Floyd’s death have shifted the national conversation and demands for change in policing and funding.

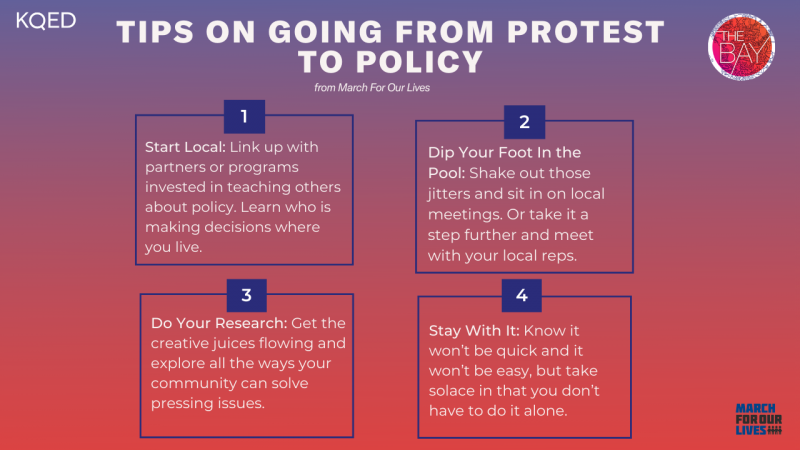

The March for Our Lives protests can be added to the list. After the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, in February 2018, an estimated 2 million people in 387 congressional districts across the country protested the lack of meaningful gun control legislation. Since then, the organization has done bus tours to understand how gun violence affects communities, and registered over 50,000 new voters — contributing to record youth voter turnout during the 2018 election. In 2020 March for Our Lives wrote specific policy demands for the Biden-Harris administration.