To be honest, The Shuei-Do Manju Shop is not quite a hidden gem. It was established in 1953, and word has been out for almost 70 years now. But hidden or not, it’s certainly a gem — There’s almost always a line at this little shop on Jackson Street, the main drag in San José’s Japantown.

The mochi made here by hand is so soft, so pillowy, one Instagram follower described them as “baby cheeks,” and this journalist (cough) can confirm the description is accurate.

“They’re some of the best I’ve ever had. It’s always nice and fresh,” said Gene Takahashi from the Takahashi Market in San Mateo (another hidden gem, by the way). “I have a legion of addicts that come shopping at my store, looking for this.” He drives down twice a week to pick up 40 pieces of mochi for his store on Thursdays, and 80 to 90 on Saturdays.

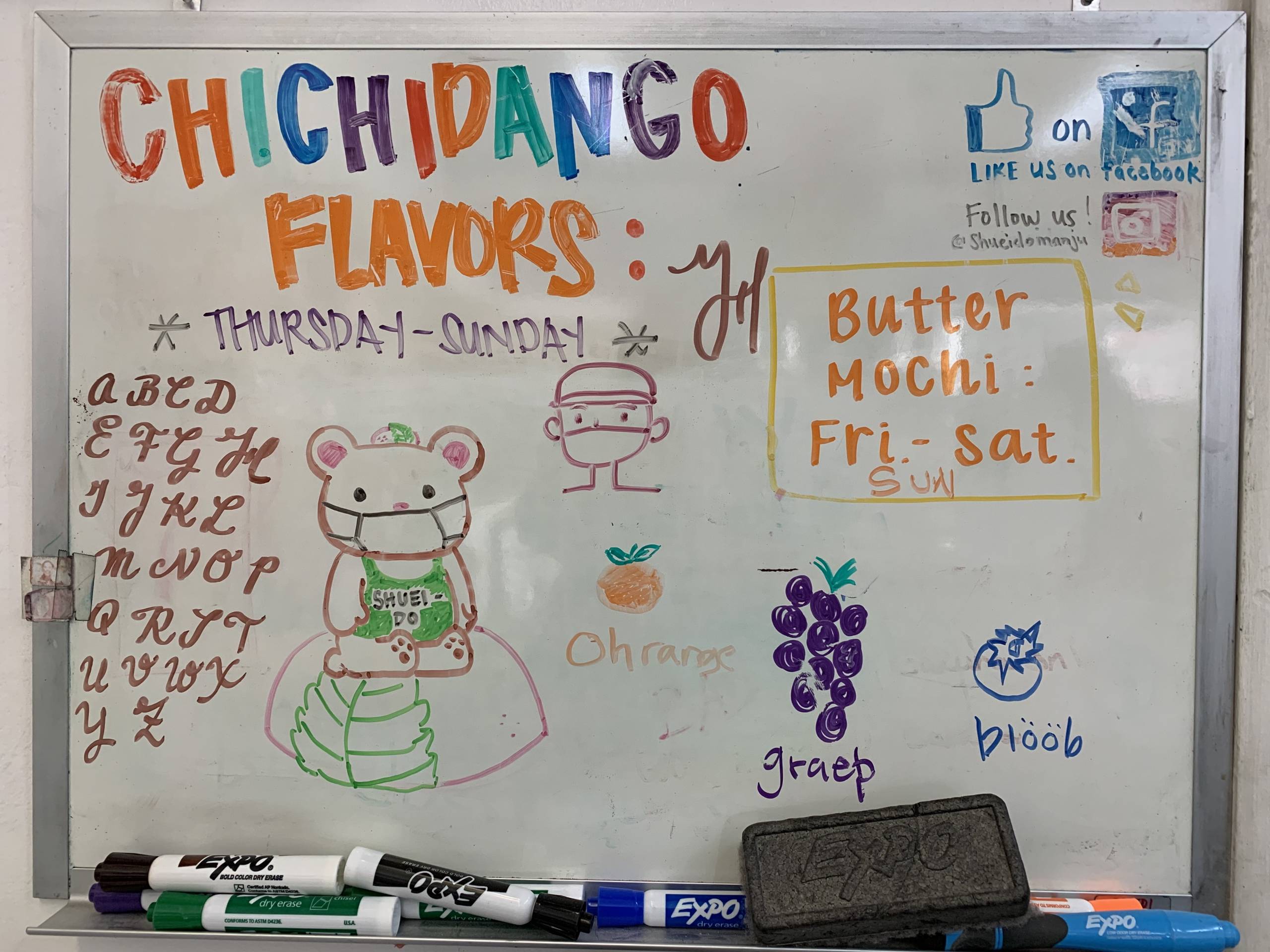

If Takahashi miscalculates demand, and the treats don’t sell out, he’ll be unable to resist eating what’s left, especially the Kinako (top row, center in the photo below): That’s the mochi filled with white lima bean paste, covered on the outside with a blizzard of soybean flour.

“There’s a trick to eating it,” Takahashi advised. “You have to make sure and take a breath first before you bite it, so you don’t inhale, and sneeze, and get brown powder in the air!”

Japanese teatime sweets are called wagashi, and there are hundreds of varieties, many regional and seasonal. Here in the U.S., much of what you’ll find in supermarkets has been shipped directly from Japan. There are even Japanese chains like K. Minamoto that feature stores in California and beyond.