The curriculum underwent several drafts over three years and was subject to heated debate before winning approval in March.

An initial 2019 draft of the model curriculum drew widespread criticism from those who claimed it was left-wing, anti-Semitic and not inclusive enough. At the time, state Board of Education President Linda Darling-Hammond called for a major overhaul.

“A model curriculum should be accurate, free of bias, appropriate for all learners in our diverse state, and align with Governor Newsom’s vision of a California for all,” she said in a 2019 statement. “The current draft model curriculum falls short and needs to be substantially redesigned.”

The new version focuses on four historically marginalized groups that are central to college-level ethnic studies: African Americans, Chicanos and other Latinos, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and Native Americans. It also includes lesson plans on Jews, Arab Americans, Sikh Americans and Armenian Americans, groups who were largely left out of the previously drafted curriculum.

State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond has championed the model curriculum as a way to help students of color see themselves reflected in what they learn, and also to learn about their own histories.

The legislation adds the completion of an ethnic studies course to other standard graduation requirements, including three years of English and social studies, two years of math and science, among others. It gives a few years’ lag time so schools can prepare.

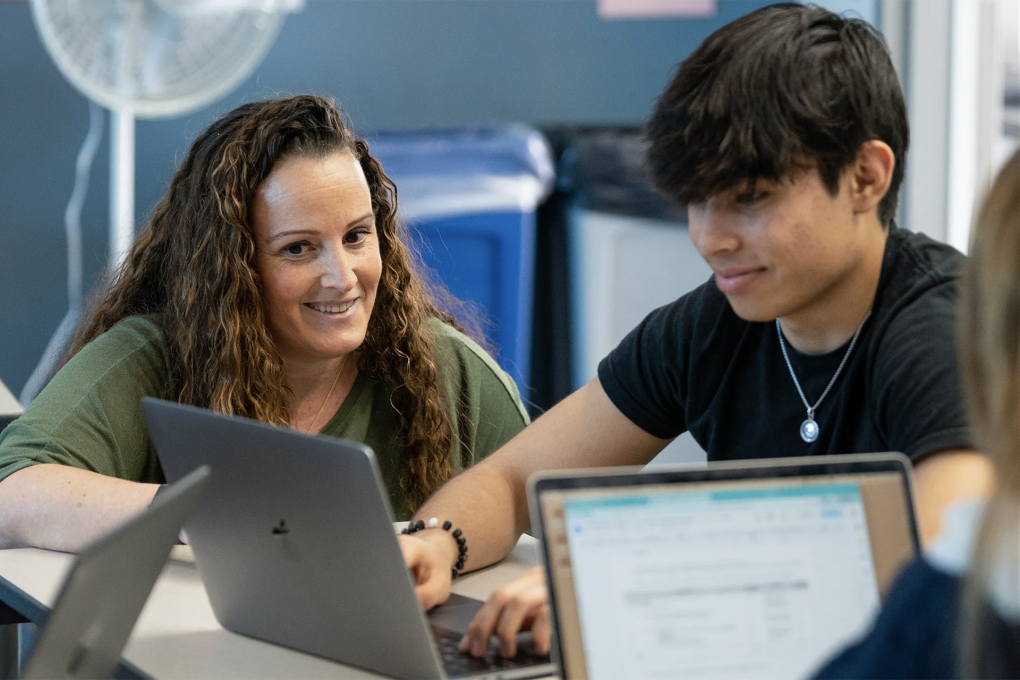

“Schools can’t just flip the switch and be ready. This gives school districts plenty of time to get their curriculum in place and hire well-qualified teachers to teach these classes,” Medina said.

Several of California’s largest districts already have begun offering ethnic studies courses, with some making them a graduation requirement. Among the trailblazers is the Fresno Unified School District, which this year began requiring its students to complete a 10-credit, two-semester ethnic studies course. Meanwhile, Los Angeles Unified plans to fully implement ethnic studies as a graduation requirement by 2023-24.

In San Francisco, where high schools have offered ethnic studies as an elective since 2015, students will be required to take two semesters of ethnic studies courses to graduate, starting in 2028.

Ethnic studies also was made a requirement this year for the state’s community college students seeking an associate’s degree.

Other states have taken different approaches. Oregon is developing ethnic studies standards for its social studies curriculum and, beginning this year, requires the subject in K-12 curriculum. Last year, Connecticut approved a law requiring all high schools to offer courses in Black and Latino studies by the fall of 2022.

Several GOP-led states have taken the opposite tack, banning the teaching of so-called critical race theory in K-12 schools or limiting how teachers can discuss racism and sexism in the classroom.

Educators say it is fitting that California has taken a lead in ethnic studies legislation, and that it’s long overdue. More than three-quarters of California’s 6 million public school students are not white.

“At a time when some states are retreating from an accurate discussion of our history, I am proud that California continues to lead in its teaching of ethnic studies,” Secretary of State Shirley Weber, a former academic who created an ethnic studies program at San Diego State University in the 1970s, said in a statement.

This post includes reporting from Jocelyn Gecker of The Associated Press.