Jump to resources:

In this episode of The California Report Magazine, health reporters Lesley McClurg and April Dembosky take us inside hospitals and clinics to meet people dealing with substance addiction who are getting help in new ways. For the first time, doctors and caregivers are asking: What do you need from us?

Last year more than 93,000 people died of drug overdoses nationwide, more than 10,000 of them in California. The public health crisis, which has spiked during COVID, is taking a horrific toll on communities and cities across the state.

For decades the state’s approach has been to punish people who do drugs. But it hasn’t worked.

“It’s more than a failure, it has been incredibly harmful,” said Dr. Monish Ullal, internal medicine physician and associate medical director of the Bridge clinic at Highland Hospital. “I think the war on drugs is one of the most disappointing things that our country has done in the last 30 years.”

Now policymakers are switching gears by recognizing addiction as a disease needing medical attention. California is investing large amounts of money in new models of treatment for those dealing with substance addiction. Two new programs are showing promise, and becoming models for the rest of the country.

Emergency rooms anchor recovery efforts

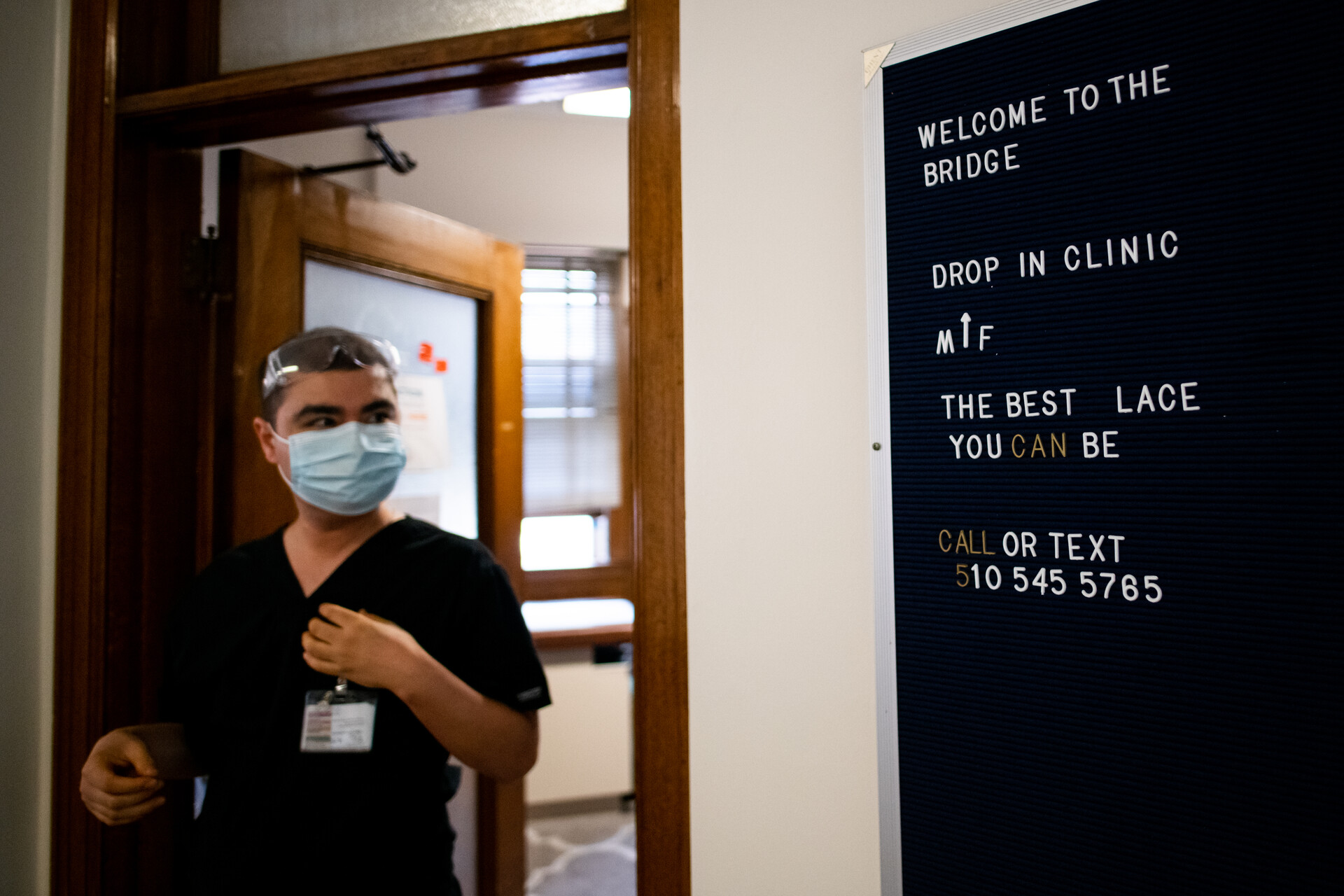

The first initiative is called CA Bridge, and its goal is to initiate treatment for patients with a substance use disorder in the emergency department. It may be hard to believe, but treating substance addiction within a hospital is fairly recent strategy.

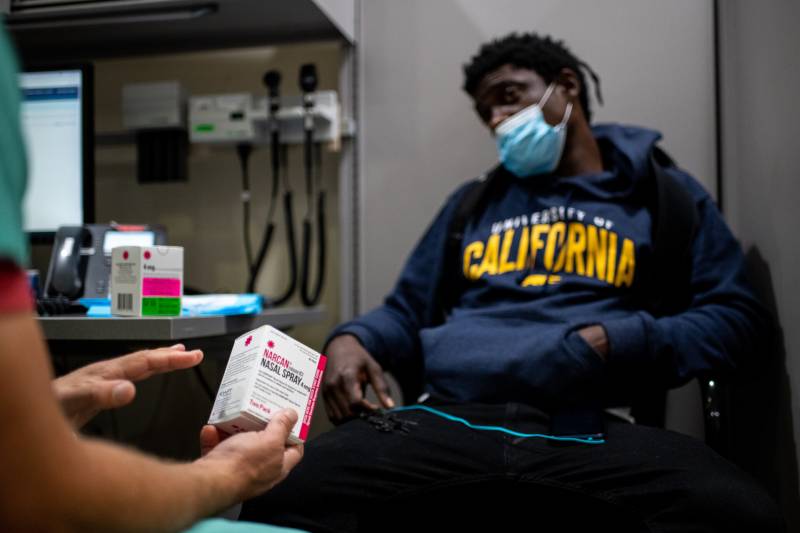

The program has a two-pronged approach. First, emergency medical physicians are trained to dispense medication to treat opioid use. Once a patient is stable, they are assigned a counselor or “substance use navigator” to ensure a strong hand-off to long-term treatment once they leave the ER.

“Just letting them know it’s OK. We got you,” explained Christian Hailozian, a substance use navigator at Highland Hospital. “That extra kind of hand-holding that these patients need to really start that journey of recovery.”