Duane “Yellow Feather” Shepard stands at the top of a narrow park that slopes downward toward a lifeguard training center and panoramic views of the Pacific coast.

“We’re looking over the horizon at a beautiful, beautiful ocean,” Shepard says. “It’s blue, serene — it’s quiet. It’s just a gorgeous, gorgeous view.”

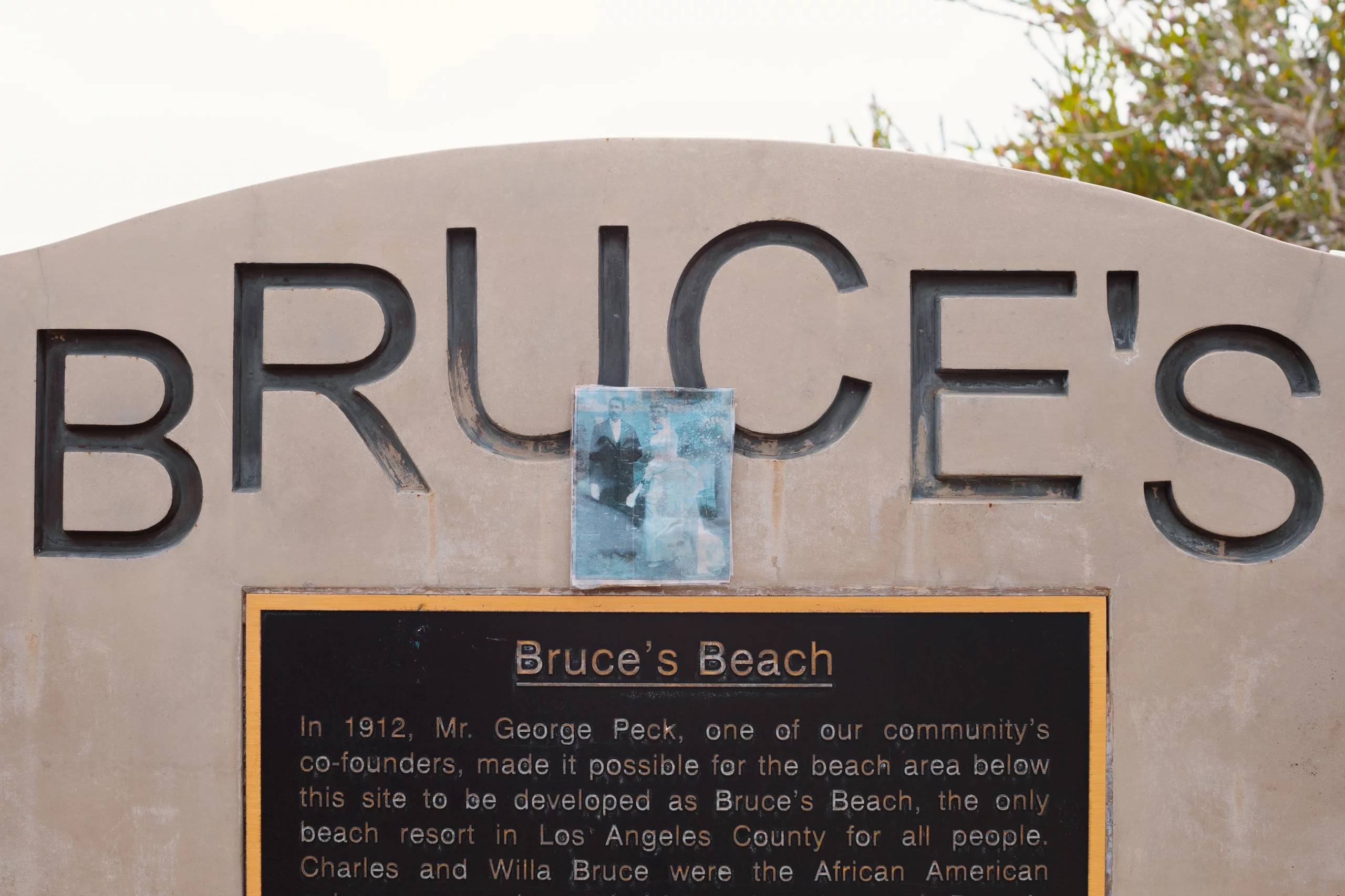

For Shepard, this oceanfront park known as Bruce’s Beach — located in Manhattan Beach, just south of Los Angeles — holds a painful history. “This is the land that our family used to own,” he says.

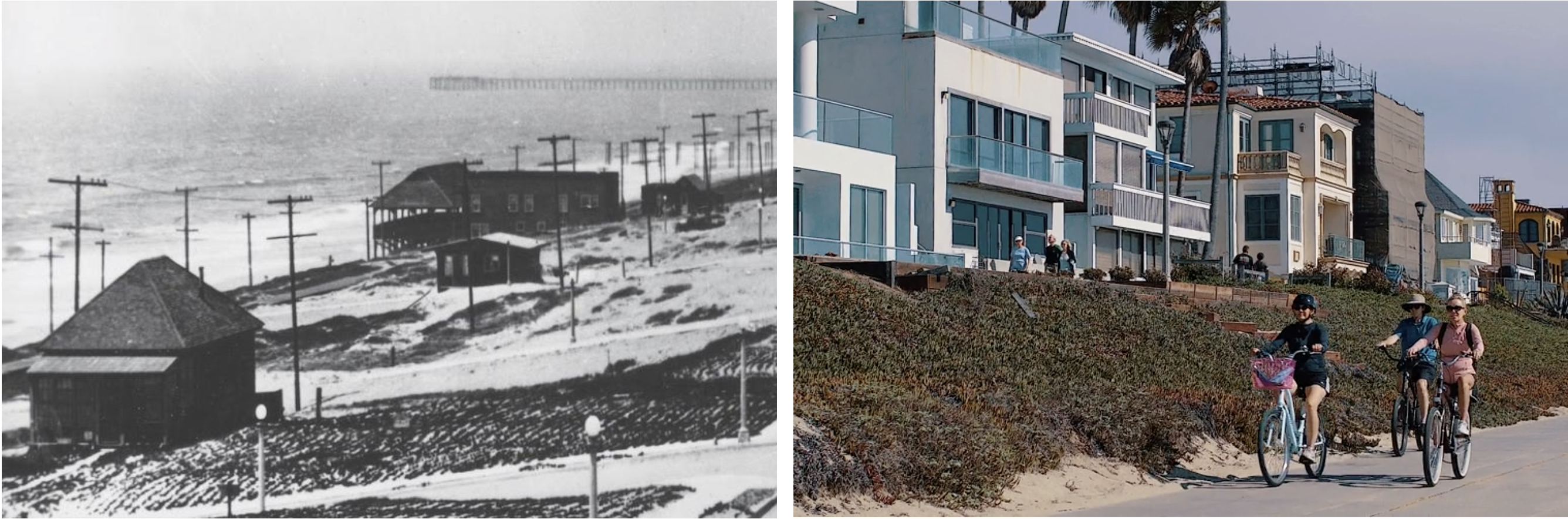

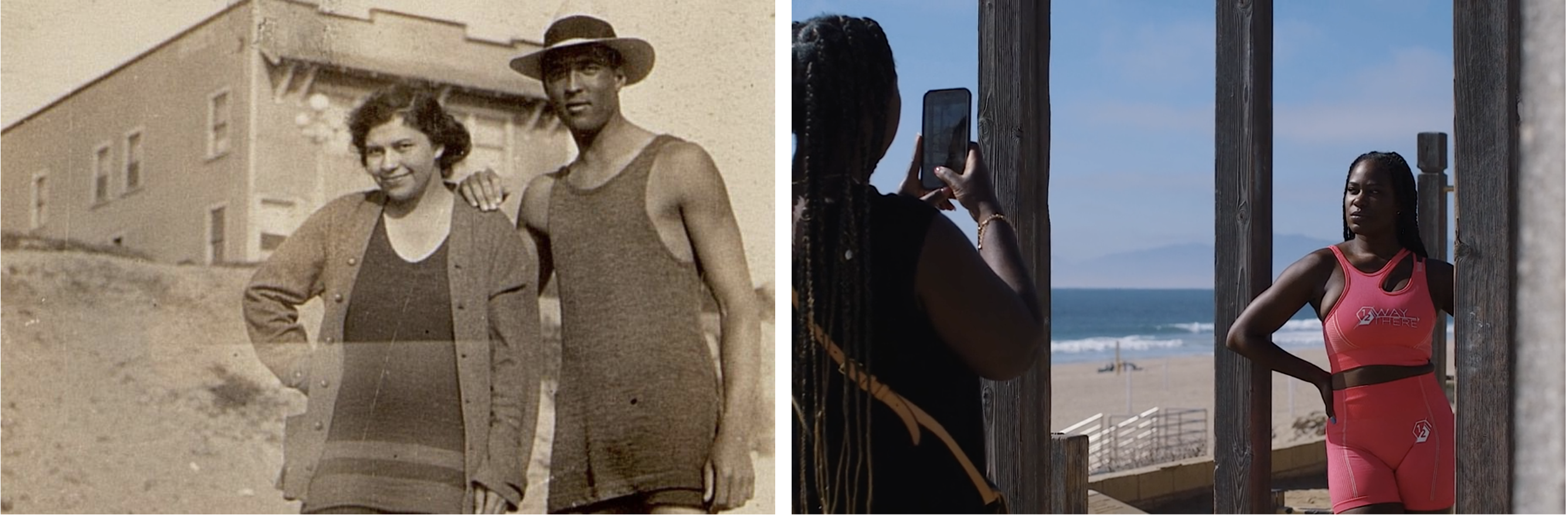

Shepard’s ancestors, an African American couple named Charles and Willa Bruce, owned this land a century ago. The couple built a beachfront resort called Bruce’s Beach Lodge in 1912 and welcomed Black beachgoers with a restaurant, a dance hall and changing tents with bathing suits for rent.

But the Bruces were run out of Manhattan Beach and forced to shut down their successful resort. Their property was seized by the city, and they lost their fortune. For years, the land was owned by the county of Los Angeles — until last month, when California passed a law that allowed the property to be transferred back to the couple’s descendants.

The historic Bruce’s Beach case is inspiring social justice leaders and reparations activists to fight for other Black families whose ancestors also were victims of land theft in the United States.

A Black resort faced harassment from white neighbors

Shepard, a cousin of the direct descendant of Charles and Willa Bruce, says Bruce’s Beach offered a refuge for Black patrons during the Jim Crowe era.

“There weren’t many areas where Black people could get into the water along the entire coast of California at that time,” Shepard, 70, tells NPR. He’s a clan chief of the Pocasset Wampanoag Tribe of the Pokanoket Nation.

“[Bruce’s Beach] was a place where people could have social functions,” he says. “You had Black entertainers, actors and actresses, jazz artists, Black politicians as well as business owners and socialites.”

However, some white residents of Manhattan Beach feared an “invasion” by the African American community, according to local historian Robert L. Brigham’s 1956 Fresno State master’s thesis “Land Ownership and Occupancy by Negroes in Manhattan Beach, California.” White residents set up barricades to keep Black beachgoers from getting to the ocean, and the Ku Klux Klan, active along the California coast, reportedly planned attacks against the Bruces’ resort.

“They slashed tires, they burned mattresses under the porch of the resort, they tried to blow up a gas meter of one of the residents here,” Shepard says. “They had 24/7 phone campaigns and made threats against Willa and her family.”

The city of Manhattan Beach seized the resort

In November 1923, a white realtor named George H. Lindsey approached Manhattan Beach’s Board of Trustees with an option to condemn Bruce’s Beach through the Park and Playground Act of 1909, according to an April 13, 2021, report by the Bruce’s Beach Task Force, a resident-led task force appointed by the Manhattan Beach City Council last year.

By 1924, Manhattan Beach city officials invoked eminent domain, claiming the city would build a public park over 30 lots, including the Bruces’ land and four other lots owned by African American families.

Bruce’s Beach resort was shuttered and demolished, and the property sat vacant for decades. Willa and Charles Bruce requested $120,000 for both damages and the value of their property, but the city granted them $14,500.

Today, the two parcels of land are worth an estimated $75 million.

On Sept. 30, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed SB 796, authorizing the county to transfer the land back to the Bruce family after nearly 100 years.

On Tuesday, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted unanimously to begin the process of transferring the land. That process also will include confirming the Bruces’ rightful heirs.

“Today, we’re making history,” Newsom said at the ceremony held on Bruce’s Beach. “I’m proud to be here, not just for the descendants of the Bruce family, but for all of those families torn asunder because of racism.”

Black landowners have faced eminent domain abuse for generations

Bruce’s Beach stands as just one example of land theft that’s taken place across the United States through violence, intimidation and legal maneuvers. For generations, Black landowners like Willa and Charles Bruce have been victimized by eminent domain abuse and unjust property laws.

“One of the reasons why the Bruce’s case has been generating so much attention is because it represents the first instance in the history of the United States where an African American family or community that had their property taken unjustly, ended up having it returned,” says Thomas W. Mitchell, a property law scholar at Texas A&M University. He’s worked to reform discriminatory policies that have stripped African American people of their land.

Mitchell is part of a research team called the Land Loss and Reparations Research Project, which is trying to put an economic value on agricultural land unjustly taken from Black farmers over the last hundred years.

“Our research team has come up with a preliminary estimate of $300 billion,” Mitchell says, noting that it only accounts for the farmland itself. “We’re also going further and saying that as a result of losing this land, we lost the ability to benefit from the land ownership in terms of families getting loans to send their children to college, which then has a negative impact on economic mobility — and that’s just Black farmers.”

Mitchell estimates the total loss of generational wealth for Black Americans across the U.S. falls into the trillions.

But families such as the Bruces whose property was taken generations ago don’t have legal recourse to get their land back, Mitchell says. Statute-of-limitation restrictions prevent families from successfully filing lawsuits.

Mitchell points to the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 in Tulsa, Oklahoma, when white mobs tried to destroy what was known as Black Wall Street.

“Yes, there was a state commission. Yes, it did do a detailed report. Yes, that detailed report documented tremendous and horrible abuses and killings and burning of businesses and taking of property,” he says. “But it didn’t lead to one penny — it didn’t lead to a single property being returned.”

Bruce’s Beach had a different outcome because the government actually stepped in to make amends for a historical wrong. The California Legislature passed a law allowing for the land to be given back to the Bruce family, making it a unique case.

“Is the Bruce’s Beach case a recognition that the time has come for real racial justice in this country?” Mitchell asks. “Can this serve as a template for providing effective redress to other African American families who have had their property taken unjustly? We’ll see.”

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))