What are you?

'What Are You?' Artist Kip Fulbeck Gives Mixed-Race People a Chance to Answer in Their Own Words

It’s a question that artist Kip Fulbeck has heard since childhood. He’s not alone: Most mixed-race people get asked that question all the time. The answer can be complicated, and for multiracial folks who straddle many identities, just being asked the question can feel isolating.

But, as Fulbeck has explored throughout his career, it can also feel invigorating and rich to belong to multiple communities, and to celebrate that complexity.

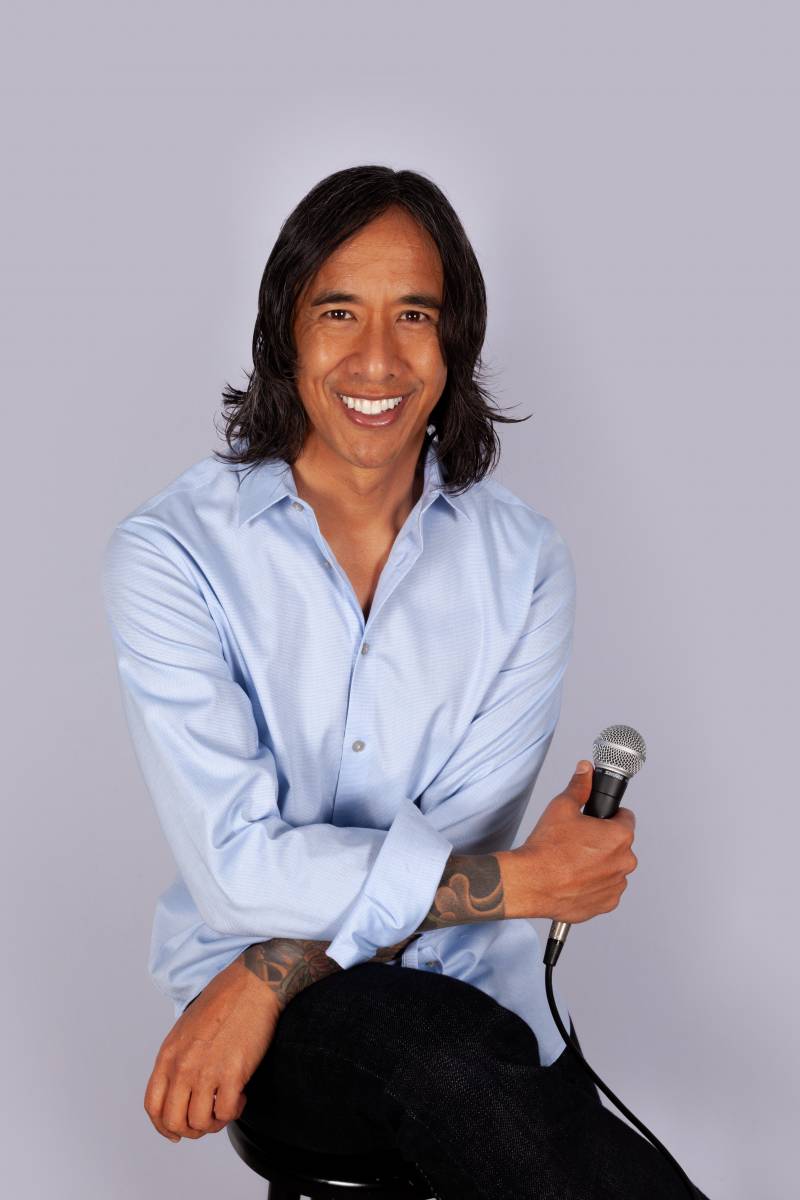

For more than two decades, Fulbeck, a filmmaker and a professor of art at UC Santa Barbara, has traveled around the country to photograph other mixed-race people and let them answer the question “What are you?” in their own words. His two most famous exhibits, “The Hapa Project” and “Mixed: Portraits of Multiracial Kids,” both were both featured exhibitions at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.

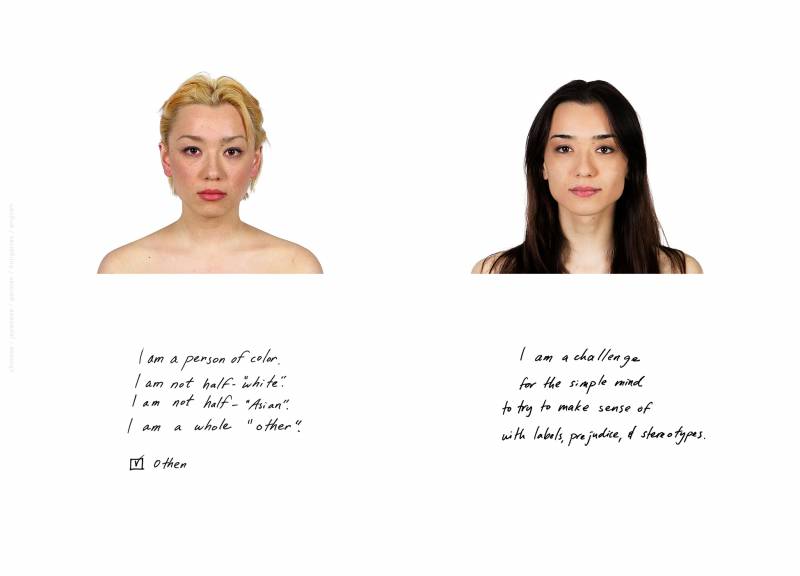

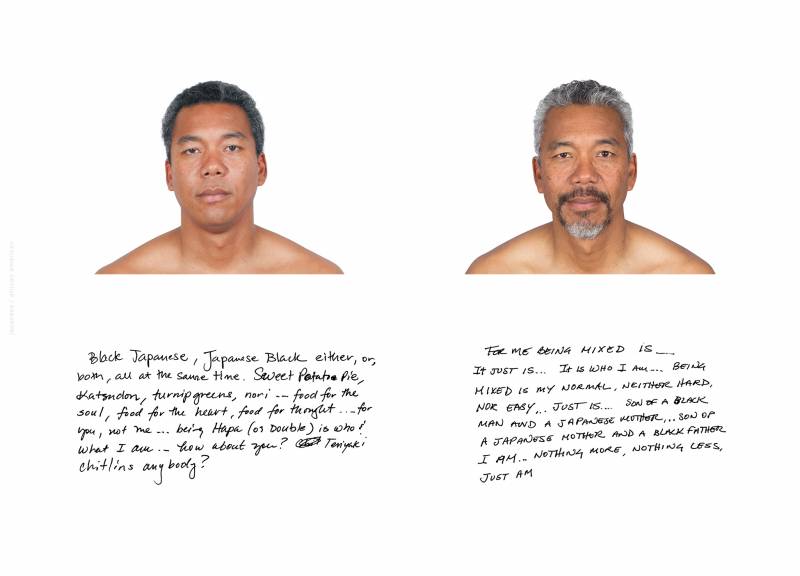

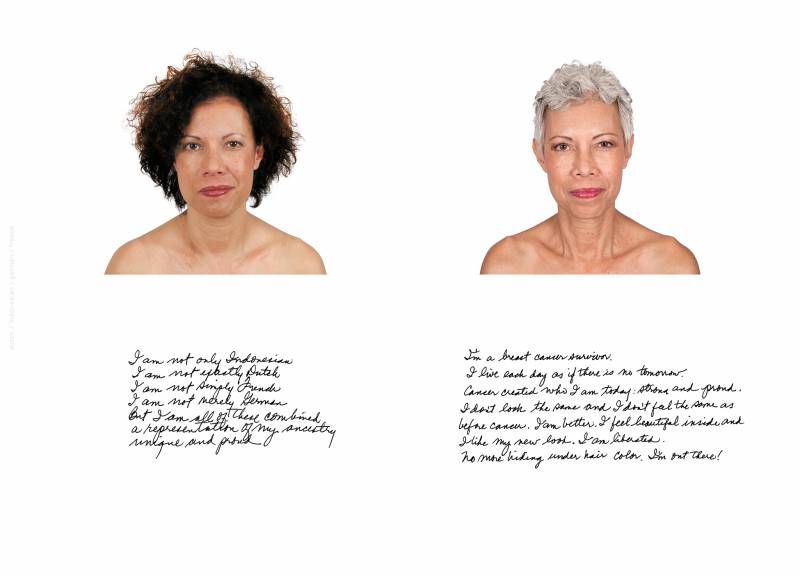

The Hapa Project featured hundreds of identically composed portraits, all shot from the collarbone up, of mixed-race people. Accompanying captions, written in the photo subjects’ own handwriting, featured answers to the question “What are you?” in their own words. Fifteen years later, he followed up and photographed 130 of those participants, to show not only their physical changes over time, but also their differences in perspective and outlook on a rapidly changing world.

Fulbeck also published a book, “hapa.me,” to capture these responses. His book “Mixed: Portraits of Multiracial Kids,” featured a forward by Barack Obama’s sister, Maya Soetero-Ng, and an afterward by Cher, known for her famous song “Half-Breed.”

Fulbeck sat down with The California Report Magazine to reflect on his work as part of our project probing the mixed-race experience.

He said that growing up with a Chinese mom and white American dad, he often felt out of place. At home, he was the only one of his siblings who was mixed race.

“I grew up in a very Chinese household where Cantonese was spoken. And we spent every weekend in Chinatown, in LA,” he said. “I grew up as the … ‘white kid.’ I didn’t speak [the] language, didn’t like the food, didn’t get the culture.”

And then in school, Fulbeck said, “I was the only Asian kid. And so I had no real cultural footing.” He remembers being bullied for being Chinese, when the Chinese community didn’t seem to accept him either.

That created a sense of isolation, and for Fulbeck, not even his family could relate to his experience.

“When you’re mixed, your parents don’t get to tell you what it was like. They don’t get to say, ‘When I was a kid, it was like this,’ because they don’t know,” he said.

Fulbeck said he struggled as a kid whenever he was asked to fill out a form detailing his race. Back then, those forms didn’t let you choose more than one racial background.

“You get that questionnaire, the ‘check one box,’ which is ridiculous,” said Fulbeck. “[For] a 7-year-old to have to pick Mom or Dad is not a fair question. I remember being a little kid thinking like, ‘Well, do I love my dad today or my mom?’”

That isolation helped spark his portrait series, “The Hapa Project,” where Fulbeck photographed mixed-race people and let them define who they are with a handwritten caption authored by each photo subject. Hapa is a Hawaiian word for “part.” It’s used in Hawaii to describe people who are part Asian or Pacific Islander, though since Fulbeck first debuted his project in 2001, there’s been heated debate over whether the term should be used more generally to define mixed-race people.

Traveling around the U.S. for The Hapa Project, Fulbeck found that mixed-race people were eager to write their own stories.

“No one gets to tell you who you are,” Fulbeck said. “And people, if you don’t define yourself, people define you and they don’t do a good job of it and it doesn’t really work. So I always say it’s kind of your responsibility.”

In the years Fulbeck has undertaken this work, mixed-race people — and the idea of mixed-race identity — have become more visible in America.

In January, Kamala Harris became the first Black person and first Asian American to be sworn in as vice president. And according to data from the latest U.S. Census, California saw a 217.3% increase in people who identify with two or more races from 2010 to 2020.

But as a kid in the 1970s, Fulbeck had to turn to fictional characters to see himself reflected.

“The funny one that sticks out to me as a child was ‘Star Trek,’ the original series,” said Fulbeck. “They always took Spock and would say, ‘Are you human or Vulcan?’ and he would say, ‘I’m both.’ I remember being a kid going, ‘I get that.’”

Fulbeck said mixed-race people are often left out of — or not fully let into — their own communities.

“People are defining you according to this boundary, that you have to be ‘this much’ this,” said Fulbeck. “You have to speak this language. You have to take off your shoes, whatever it is. It’s like if you’re going to go off those definitions, then you’re going to be in a world of hurt. You have to find your own way to define yourself.”