Hamasaki and other commissioners said that the chief’s allegations appeared to target only technical violations, if any, of the agreement. Pointing to a judge’s ruling that no evidence was withheld in the Stangel case, multiple commissioners said repeatedly that they didn’t see how any investigation was substantively derailed by the district attorney’s alleged violations of the agreement.

District Attorney Chesa Boundin called in to public comment as the meeting stretched past 11 p.m.

“The decision to withdraw is a massive violation of public trust and a huge step backwards in police reform and police accountability,” Boudin said, repeating his response from last week that the police department regularly violated parts of the agreement.

“I don’t pick up my ball, walk off the field and go home,” Boudin said. “I don’t go to the press. I call the chief to try to work it out. And we’ve had a really good open channel of communication until last week.”

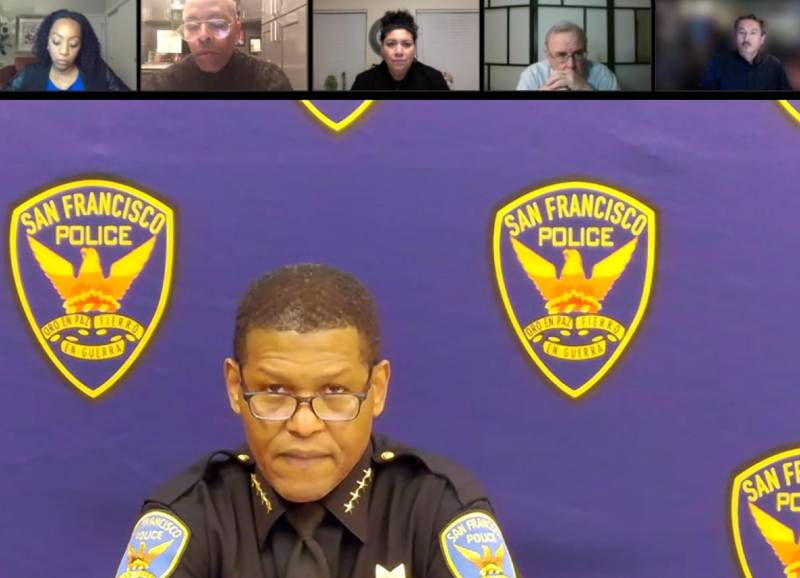

Scott and Boudin met Wednesday, both officials said, to discuss the dispute, but they have not reached a resolution. State Attorney General Rob Bonta has put a toe into the fight, writing in a letter to both Wednesday that he would do “all I can to assist both parties in resolving any issues that have recently been identified as challenges to the progress achieved to date.”

The carefully worded statement indicates two things: First, the attorney general is not yet consenting to take over these investigations directly, which Scott asked for when he announced plans to cancel the agreement with the district attorney.

Second, the state attorney general’s office has an interest in maintaining independent investigations of San Francisco police shootings. As noted by several commissioners as well as residents who called into public comment, the agreement Scott says he’ll cancel is a crucial piece of ongoing reform of the SFPD that’s overseen by the state Department of Justice.

Beyond the politics and sour grapes, Commissioner Max Carter-Oberstone summarized the concern going forward.

“If you’re going to take the extreme step of tearing up the MOU, how could we do that without having a plan in place?” Carter-Oberstone asked Scott. “What is going to happen if, God forbid, an officer shoots someone one month from now and this MOU has lapsed? This was not, in my view, the most responsible course if you thought that it was necessary to pull out of this.”

“Does anybody care what the workforce who has to do the work, how they see this?” Scott said in response. “Regardless of whether a plan is in place or not, what I’m hearing from you and this commission is to stay in a situation that your entire police department does not trust. And that has an impact on everything that we do.”

The public battle and what it represents for police reform and San Francisco’s embattled district attorney, who faces a recall election in June, has stirred massive public concern, evidenced by the dozens of city residents who called in to the meeting to comment.

“What Chief Scott did was right, and he’s looking to the attorney general’s office for support and options as part of his plan,” said one caller who identified themself as a resident of San Francisco. “This is why this city is so messed up because you’re on the wrong side of the equation.”

“For the first time in history there are charges in San Francisco against police officers who have murdered Black men,” another caller who did not identify themself said. “This is Scott’s obvious last-ditch effort to keep cops from ever going to jail in San Francisco.”

There’s no indication that the standoff will end in the coming days, but there is a deadline. The police chief’s decision to cancel the agreement could become final as early as Feb. 17.