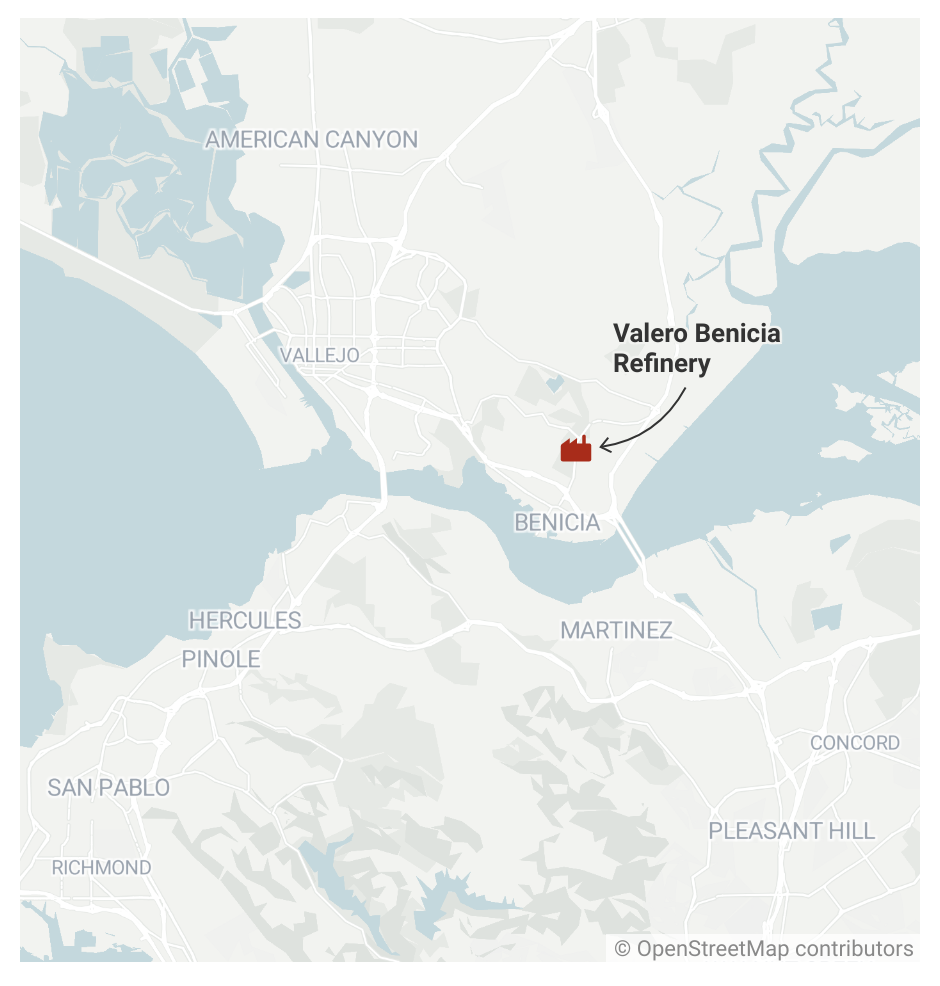

Officials in Benicia and Solano County want to know why Valero’s oil refinery there was able to release excessive levels of hazardous chemicals for more than 15 years before regional air regulators discovered the emissions — and why those regulators failed for another three years to alert local communities to the potential danger.

A Bay Area Air Quality Management District investigation launched in November 2018 found that one refinery unit produced pollutant emissions that were, on average, hundreds of times higher than levels permitted by the agency.

The emissions consisted of a variety of “precursor organic compounds,” or POCs, including benzene and other toxic chemicals.

An air district rule limits the release of such compounds to 15 pounds a day and a maximum concentration of 300 parts per million. The district’s investigation found that from December 2015 through December 2018, POC emissions averaged 5,200 pounds a day — nearly 350 times the daily limit. The average POC concentration recorded during the first year of that period was 19,148 parts per million, more than 60 times the level set by the agency.

Those findings led the air district to issue a notice of violation to Valero in March 2019. But it wasn’t until late last month that the agency went public and announced it would seek to impose an abatement order requiring the refinery to halt the excessive pollution releases.

“That was the first I had heard of it,” said Benicia Mayor Steve Young, one of four members of the city council who say they want to know why the community was not told earlier.

“We should have been notified by the air district when this was first discovered in 2019, and certainly while negotiations with Valero were going on,” he said.

The Solano County agency responsible for inspecting the Valero refinery and investigating incidents there says it was also left out of the loop.

Chris Ambrose, a hazardous materials specialist with the county’s Environmental Health Division, said in an email his agency “was never formally notified by or requested to participate in BAAQMD’s emissions investigation.”

A health risk assessment carried out by the air district in 2019 found that the refinery’s release of benzene and other pollutants posed an elevated risk of cancer and chronic health threats and violated several agency regulations.

Solano County Health Officer Bela Matyas told KQED that because the wind often pushes refinery emissions away from Benicia, the refinery’s prolonged pollution releases didn’t likely pose any extreme risk to residents.

“But it doesn’t excuse the process. It doesn’t excuse the failure to adhere to standards and it doesn’t provide any excuse for the fact that the city of Benicia was put at some risk as a result of these emissions,” Matyas said.

The air district, which plans to hold a virtual public workshop on the Valero releases on Thursday night, is defending its decision to not alert local officials earlier.

“To protect the integrity of the air district’s investigation and ensure that Valero is held accountable, we were not able to notify the city of Benicia until the investigation was concluded,” district spokesperson Kristine Roselius said.

“Going forward, the air district is committed to additional transparency around these types of ongoing violations, to putting companies in front of our hearing board in a public forum where information can be shared, and working to ensure these types of cases are brought into that forum as quickly as possible,” she said.

The hearing board Roselius referred to is an independent panel created under state law to rule on issues that arise at individual facilities that the air district regulates. The board is scheduled to consider the district’s abatement order at an all-day public session on March 15.