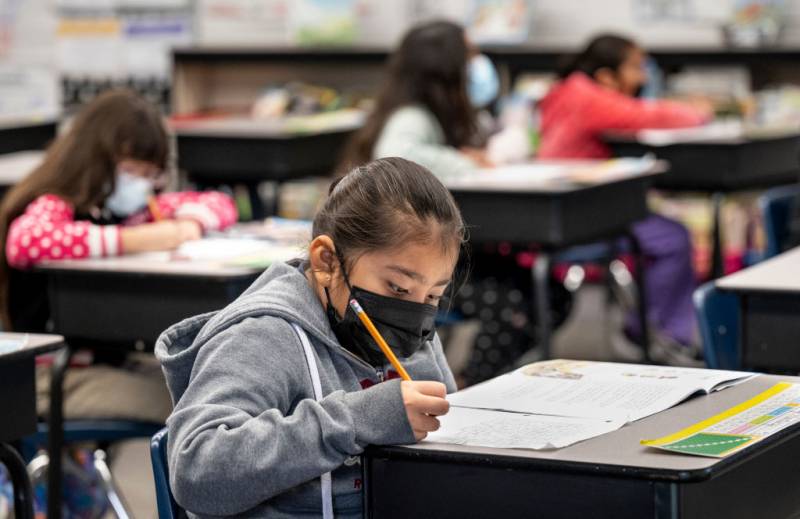

“We know that masking, strong testing programs and having good school ventilation systems in place have been key to ensuring the stability of in-person learning,” the statement from CTA President E. Toby Boyd said, adding that changes "will disrupt and destabilize school communities.”

Jeff Freitas, president of the California Federation of Teachers, said the state's delay made good sense. He pointed to the markedly higher rates of COVID-19 infection in Black and Brown communities, and the need to ensure kids in those areas are safe at school.

“So we need to look at this with an equitable lens in making sure that we are providing the safest environment for everybody and especially for the underrepresented communities,” he said.

Newsom said last week that one of the sticking points in labor negotiations was the relatively low vaccination rates for children under 12.

Only 28% of 5- to 11-year-olds in California are fully vaccinated, according to the latest state figures, compared to 89% of residents 18 and older.

“The risk is much slower to have severe disease in children than in, say, a 65-year-old adult, that's for sure,” said Dr. Yvonne Maldonado, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Stanford University. “But it doesn't mean that that child's life is not as valuable. They should be protected because the risk is still there. We put helmets on kids and put them in seatbelts — risks that are far lower of having a bad outcome.”

Ghaly declined to say whether lifting school mask requirements would be tied to specific metrics.

California has had some of the strictest mask and vaccination requirements in the country, with Newsom announcing last October a COVID-19 vaccine mandate for all public and private schoolchildren. That mandate is not expected to take effect until July, pending full federal approval for the shots.

The school mask requirements, in place since July 2020, were key to getting the state's powerful teachers unions to agree to reopen classrooms.

But the prolonged rules have furthered long-simmering frustrations among many parents and local officials, even in some particularly progressive districts.

“I think that this will transfer a lot of political pressure back down to districts,” said Brent Stephens, superintendent of the Berkeley Unified School District. “This is not a new pattern over the course of this pandemic. There have been many decisions left to localities to make that here in school districts we often feel are better made either at the state level or by people with better expertise in public health.”

In a number of more conservative regions, a handful of districts have begun to openly defy the state mandate.

In a suburb of Sacramento, the Roseville Joint Union High School District school board last week voted unanimously to start a “mask optional” policy.

And at Corona-Norco Unified School District in Riverside County, where students and parents recently protested the school mask mandate, the district said it has set up a supervised, outdoor area where students who refuse to mask up can spend the day protesting or doing schoolwork.

“When do we step out of this phase? Because we can’t stay in it forever,” said Jason Peplinski, superintendent of Simi Valley Unified School District in Ventura County. “And frankly, we can’t stay in it for much longer because, like I said, reasonable people are losing their patience.”