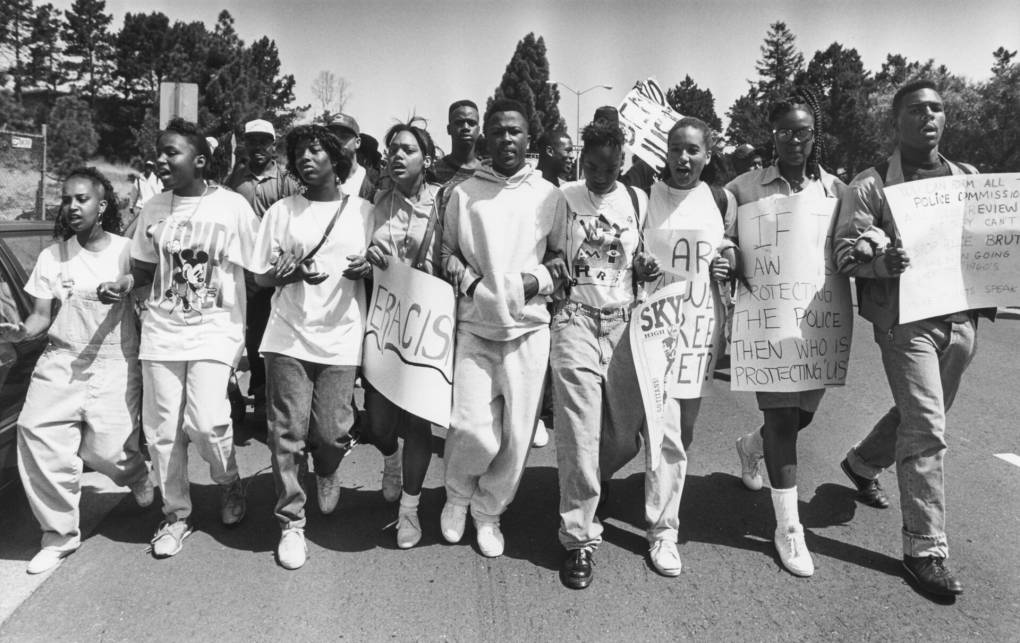

When we look at the California of today, so much of who we are is because of the Gold Rush. It’s true that people flooded into the state after gold was found in 1848, and that there were opportunities here for some fortune-seekers. But there are darker parts of that history we don’t often hear about. Some of those gold-seekers came from the South and brought enslaved people with them to mine for gold in California.

“I find it very interesting that we don’t know any of this part of California’s history,” said Bay Curious listener Doug Spindler. “And yet this is so big and so important.”

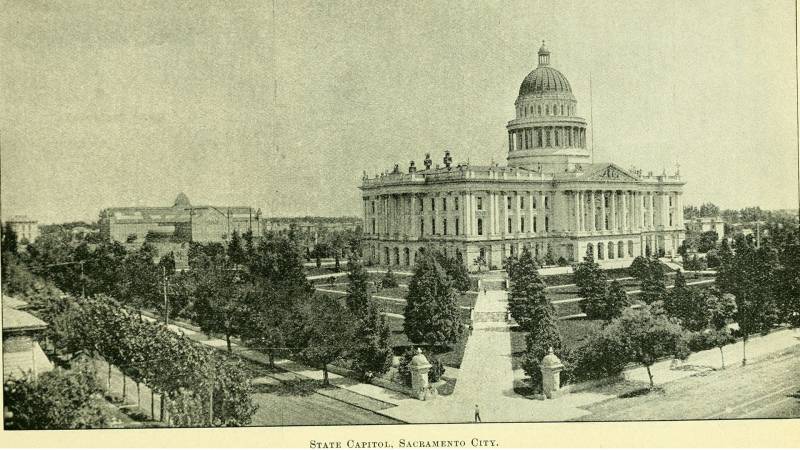

Doug came across some of this information while researching the Gold Rush era and California’s recognition of statehood soon after. California entered the union in 1850 as a “free state.” The state constitution says: “Neither slavery, nor involuntary servitude, unless for the punishment of crimes, shall ever be tolerated in this State.”

But what’s on paper is not the reality of what happened here.