Ngûyen Pham remembers where he was on March 16, 2020.

He was at his house in San José when he got a call from his workplace. “I was told to stay home and work from home,” he said. Santa Clara County had just ordered all residents to shelter in place for the next few weeks.

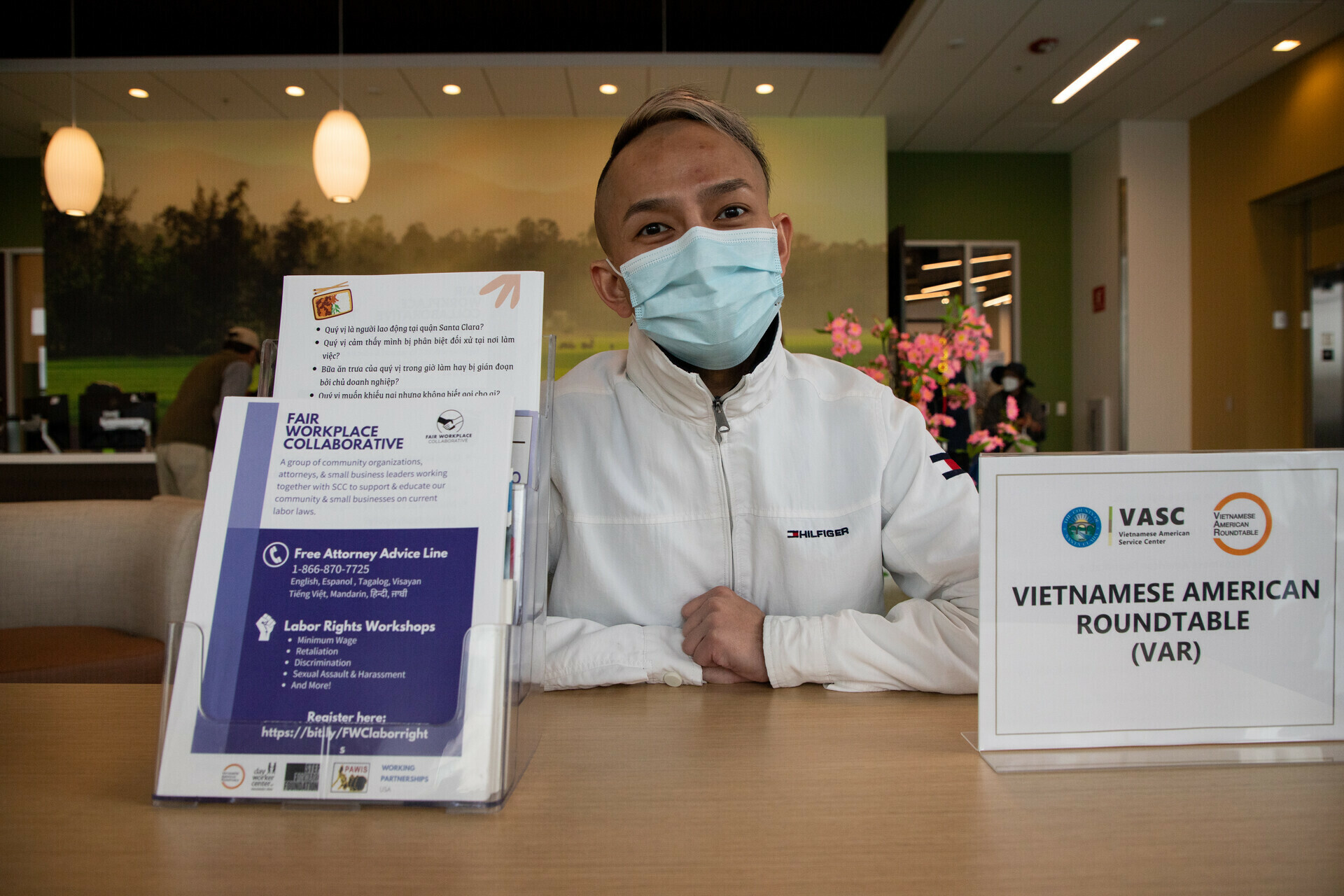

Pham works with the Vietnamese American Roundtable, a group that promotes workers’ rights and cultural programs for the Vietnamese community in the South Bay — one of the biggest Vietnamese enclaves in the country.

As nonprofits, churches and libraries closed their physical doors and turned online to keep operating, Pham realized that thousands in his community could potentially lose access to food and other essential services these places provided them with. And he knew elders in the Vietnamese community with limited access to the internet were especially vulnerable to losing this aid when they needed it most.

He started making calls. He reached out to friends and old colleagues he knew from years of being involved in social work across Santa Clara County to figure out exactly what families and elderly neighbors would need during lockdown, and how to get these services out in the spirit of mutual aid.

People responded.

Friends were delivering hot meals to the elderly and translating critical information about the coronavirus into Vietnamese. They were even collecting funds to build coffins, for those who lost their lives to COVID-19 but whose families had limited financial resources.

“Mutual aid, historically — it’s been there in the community,” Pham said. And in the Vietnamese community, he notes, “the mutual aid effort really started out from helping underprivileged folks here and in Vietnam.”

After North Vietnamese forces took control in Vietnam in 1975, the Bay Area saw an influx of Vietnamese migrants. But traditional financial institutions like banks made it difficult for recent arrivals to access credit when they needed it the most.

“Small groups would … put money together to fundraise,” said Pham. “They would request from members a donation monthly and would use that money for scholarships, to build houses and things like that.”

These strategies employed by Vietnamese families to survive tough times in the U.S. served as the blueprint for young people like Pham to organize at the start of the pandemic — a time when the Bay Area saw many mutual aid efforts spring up.

The jarring nature of a global pandemic, paired with an economic downturn that left millions unemployed and unable to pay for basic necessities, left many to turn to mutual aid when local, state and federal governments fell short of providing the kind of support they needed. Many of these efforts received widespread media attention and subsequent financial support throughout 2020.

“The pandemic really taught us a lesson that everybody really needs to rely on one another,” Pham said. “When one person is hurt, the rest of the community is in pain.”

As time went on, though, organizers say that mainstream coverage — and funding — slowly started to fizzle out in many ways. But those involved in mutual aid work, like Pham and his friends, haven’t stopped organizing.

‘Romanticized’ vs. reality

Mutual aid is work.

Organizers invest countless hours each week to raise funds, find food and other essential goods, and maintain an online presence to let folks know what resources are available.

No one knows that as well Gabriela Alemán, co-founder of the Mission Meals Coalition (MMC), a mutual aid network created in San Francisco’s Mission District a few weeks after city officials announced its shelter-in-place order in March 2020.

“People see the pictures and they like to hear the updates. But the reality is mutual aid is really, really hard,” she said.

Alemán, along with her sister Xiomara and her friend María Castro Noboa, began MMC by connecting immigrant families and seniors across the Bay Area to free warm meals and fresh groceries.

They later opened up a free fridge in the Mission where residents could drop off food so others could take what they needed — at a time when many residents had lost their jobs, and were struggling to keep up with expenses.

The group started MMC while they were holding down full-time jobs. They were doing all of this in their free time.

Soon after the fridge opened, news outlets across the region — including KQED — were drawn to MMC. Alemán acknowledges that media coverage played a big role in spreading the word about the group, but says there’s a lot more to the story.

“Mutual aid was really romanticized, especially with the fridge program,” she said. “Across the country, people were covering these fridges. They had gorgeous images of the fridges.”

“But the reality is it’s really hard to maintain a free fridge. There’s so many safety concerns around fridges — and I like to use that kind of as a metaphor for what mutual aid is,” said Alemán.

While the group still operates the fridge, they’ve grown to now distribute boxes of food to hundreds of families and workers in San Francisco and the North Bay. This also includes boxes catered specifically to folks with diabetes or prediabetes; baby food for new parents; and dental kits to promote oral health.

Food justice goes beyond providing a single meal, Alemán explains. While folks could signal what their food needs are by what they take from the fridge, there’s a lot groups like MMC could miss. Who doesn’t have access to a kitchen? Who doesn’t have time to cook a healthy meal because they work two or three jobs to make rent?

This is where the preestablished connections within the community came in. “Our community engagement comes from our señoras,” she said. “The relationships they have built across the neighborhood and WhatsApp groups is incredible. You can’t find that anywhere else.

That’s some of the critical work that was left out during the flurry of media coverage in 2020, says Alemán. And it hasn’t gotten better since.

“I feel like people have moved on from the pandemic, from talking about food equity and food work,” she said.

‘An undying love for our people’

Mutual aid must also be a revolutionary act.

That’s according to Yemi Belachew, director of operations for People’s Programs — a West Oakland-based group founded by Delency Parham and Blake Simons in 2017 that provides free meals, organizes political education workshops and organizes bail funds for detained Black protesters.

When many homeless shelters closed at the start of the pandemic, People’s Programs quickly organized to get food, shelter supplies and other goods to unhoused residents across the East Bay.

“We’re organizing for independence,” Belachew said. And each of the resources offered by People’s Programs plays a role in the group’s goal of securing Black liberation in Oakland.

“Yes, there are people who are hungry. Yes, there are people who need these material needs,” she explained. “But we’re doing that with a political objective.”

The People’s Programs’ efforts to bail out Black people arrested in the summer of 2020 during protests following the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer garnered widespread attention across social media. That visibility helped raise awareness about the food distribution work the group was doing — and folks outside of West Oakland started volunteering.

Volunteers and donations from outside the community have shifted in the past two years, but Belachew says that the support from within West Oakland among residents has stayed strong.

“When you build with us, you’re not here for one summer, one event, one moment. You’re here for the entirety of the organization,” she said. “And we’re investing in you as well.”

From the beginning, People’s Programs has envisioned creating permanent support networks for Black people in the Bay Area, Belachew says. And the media buzz around mutual aid efforts during 2020 — amplified by protests after George Floyd’s murder and the accompanying reckoning with racial justice in the country — did introduce this work to a wider audience.

But Belachew says that this profile also made it easier for institutions like governments and corporations to appropriate the term, and use it for purposes that weren’t necessarily rooted in community.