Episode Transcript

Olivia Allen-Price: Bay Curious listener Tadd Williams often finds himself driving on the 880 freeway in West Oakland. There’s this one building that’s visible from the road that he’s always wondered about…

Tadd Williams: It seemed like such a beautiful structure. I guess that was the first thing that kinda caught my eye.

Olivia Allen-Price: It’s an impressive building, in a beaux arts style that looks stately and European. The front is dominated by three grand arched windows, positioned over the entrance. Everything is very symmetrical.

But the outside is routinely covered with graffiti, and this place is surrounded by a perimeter of chain link fencing … Because it’s been abandoned for more than 3 decades.

Tadd Williams: It’s something I’ve always seen from the freeway and I just wanted to understand more about its background, you know, its history, its purpose.

Olivia Allen-Price: Turns out the building Tadd has been eyeing is the 16th street train station in West Oakland. It’s got a storied legacy that can hardly be overstated. It helped give rise to West Oakland’s Black community … and laid a foundation for activism in the town. But with all these accolades, why does it sit empty today?

On today’s show, we go inside the once grand, now derelict 16th Street Station.This episode first ran on Bay Curious in 2022, but there’s been an exciting update. So we’re bringing it back to refresh your memory. Hang out at the end for what’s new. That’s all just ahead on Bay Curious. I’m Olivia Allen-Price.

SPONSOR MESSAGE

Olivia Allen-Price: Question asker, Tadd Williams, sent us on a journey to learn about the impressive, and neglected, 16th Street Train Station in West Oakland. Reporter Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman found that for many coming to California, it was the end of the line. The opening scene in your next chapter …

Alan Laird: Oakland was a golden doorway to a new life

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: This is Alan Laird, he was born in Oakland, but before he was born, his father made the journey from Mississippi to California.

Alan Laird: And leaving the south. Um, Uh, brown paper bags and baskets worth of fried chicken and things just to make the journey. And chairs, chair cars that would not give sometimes and your back would ache and your rock and you think, and all the time about making it to that place.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: It was an opportunity to start a life away from the Jim Crow South.

Alan Laird: When the doors opened up the engine led off this last blast of steam. Ahh. You almost hear a sigh of relief, like hope is here. We made it on time. We made it all the way through that. And now we are at home, a new home.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: For many people, the first steps of this new life would be into the 16th street station.

Alan Laird: And they stop and pause for a minute, getting off the train, gazing around, not knowing what to expect beyond those, uh, highly polished brass plated doors.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Laird’s father worked as a cook on the Southern Pacific Railroad. So Laird was there a lot in the 50’s when he was a boy.

Alan Laird: I remember the smell of the hot dogs and the hot peanuts and things from it, from the little snack shop there that had all the books that you could buy to read and…

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: He says the marble floors were so polished, you could see the reflection of the chandeliers when you looked down.

Alan Laird: So I had a love affair with that station.

(music bridge)

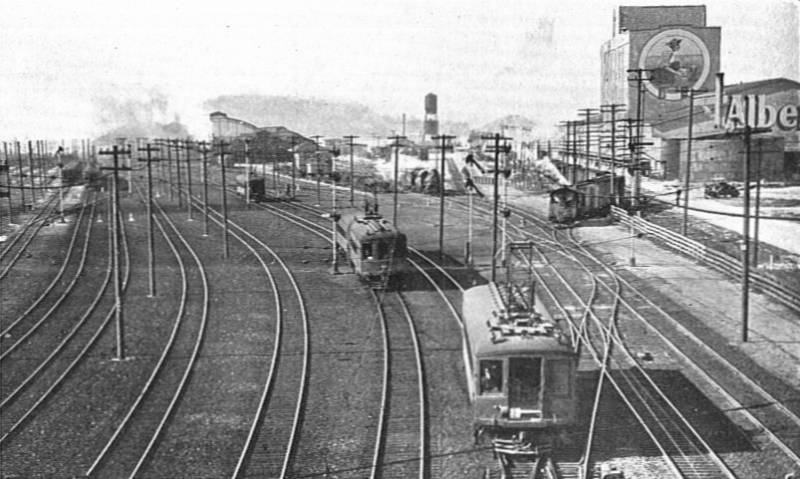

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: It was built in 1912, during the golden age of rail travel. For decades, the station was as busy as an airport is today. There would be dozens of long distance trains arriving every day.

Alan Laird: “Now on train number track 22. That Shasta Daylight coming in, now arriving.” And depending on what train my father was on, it was extra exciting.

(Music ends)

Mitchell Schwarzer: It was the grandest railroad station ever designed in the San Francisco Bay Area. That includes San Francisco, Oakland, and all the cities around. This was the big station.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: That’s Mitchell Schwarzer, professor and author of the book “Hella Town: Oakland’s History of Development and Disruption.” He says that the station was also home to a huge network of local trains and streetcars.

Mitchell Schwarzer: There would have been hundreds – 500 or more – electric interurban trains arriving from various parts of the East Bay. There would have been about 200 street cars arriving and departing every day as well.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Before the Bay Bridge was built you could take a train from 16th street station to something called the Mole. Essentially a pier that took trains out into the bay, to a terminal where people transferred to a ferry to get to San Francisco. Later, for about five years, you could even take a train across the lower deck of the Bay Bridge into San Francisco.

(Music bridge)

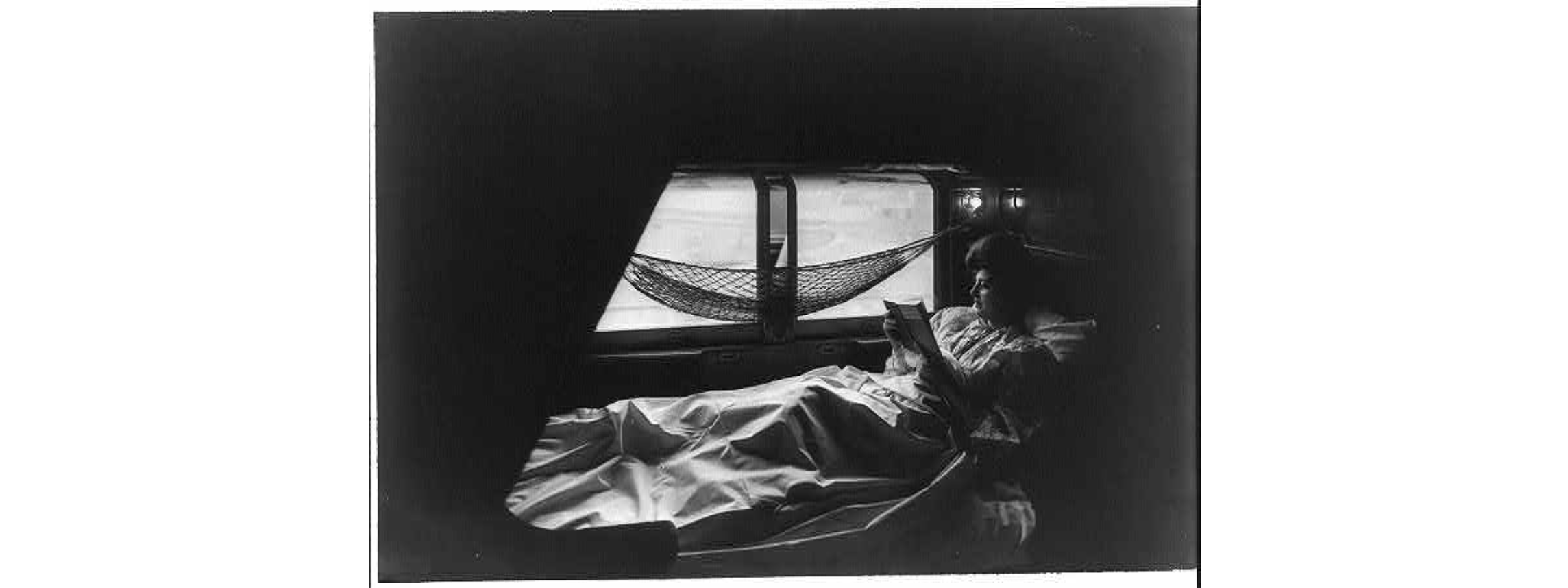

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: In the decades after the station was built, throughout the early 1900’s, you’d see all sorts of trains, but the most luxurious were Pullman Palace Cars.

Archival tape: By day or by night, Pullman offers complete rest and relaxation cleanliness, safety, and comfortable transportation for the American public.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: These trains were luxury sleeping cars, like hotels on wheels, designed for wealthy people to make the long transcontinental railroad trip in comfort. Imagine well-to-do travelers sitting on plush seats, chandeliers hanging from ceilings, windows with silk curtains and dark walnut woodwork.

Archival tape: It takes a great army of men and women to maintain Pullman standards. The yards and shops storerooms and offices work smoothly day and night.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: It was an operation. Pullman employed maids, waiters, and cooks to provide top quality service. But the porters were the most renowned part of the operation.

Archival tape: And electric bell with which to summon the porter at any hour.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: They would carry luggage, shine shoes, and basically wait on passengers every need.

Archival tape: PORTER! PORTER!

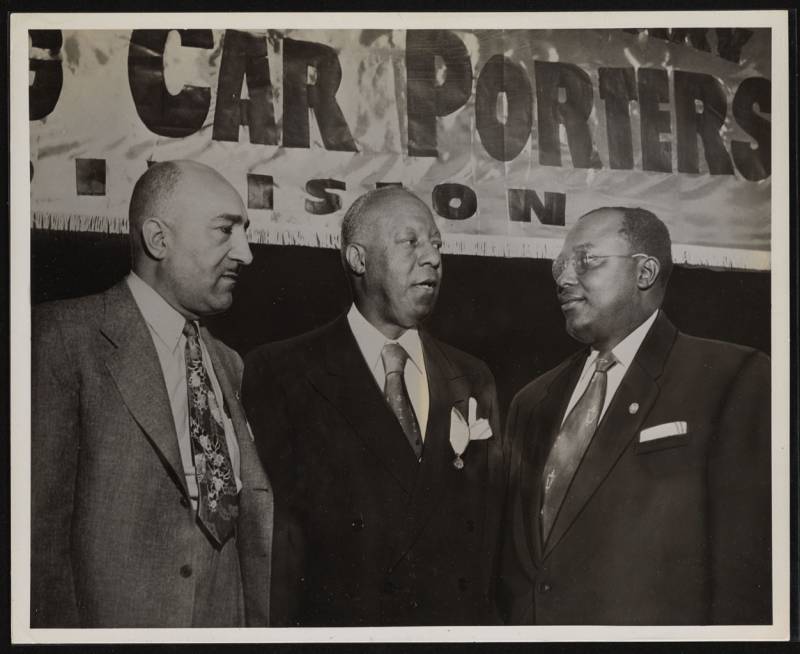

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: And the Pullman Palace Car company almost exclusively hired Black men for these jobs.

Mitchell Schwarzer: So there was that kind of racist idea of Blacks serving whites in a subsidiary role.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: They were expected to work hard, 20 hour shifts. Many customers wouldn’t even call the porters by their name, they just referred to them as George, after the founder, George Pullman. Calling someone the name of their enslaver was a tradition carried over from slavery.

Mitchell Schwarzer: But at the same time, it gave a great source of employment for Blacks around the country.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: The combination of a steady income and the ability to travel around the country was almost unheard of for Black people at the time.

(Music)

Mitchell Schwarzer: So the porters have a kind of role as ambassadors of information, right throughout the United States to Black communities.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Porters were known for distributing the Chicago Defender, the largest Black newspaper at the time, across the country, including to the south, where the paper was banned in some places. The paper helped fuel The Great Migration out of the south by informing people of opportunities elsewhere.

Mitchell Schwarzer: So they’re both, they have relatively well-paying jobs, stable jobs. They’re moving around the United States. And basically communicating to other Black communities cause they’re getting off and sleeping and then getting back on.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Because of the hard working conditions and the systemic racism, in 1925, the Porters announced they wanted to form a union. The first Black union in the country, called the Brotherhood of Sleepingcar Porters. They were based in Chicago

Mitchell Schwarzer: But the vice-president C.L. Dellums was based in Oakland.

(Music)

Mitchell Schwarzer: So Oakland takes on a very large role within the brotherhood. You know, it’s kind of, it’s kind of what the secondary headquarters of the brotherhood.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: But the struggle to unionize was a long one. It took 12 years. The Pullman company fired workers who tried to organize, and did everything they could to discourage the union. But in the end, the porters were successful, and Oakland played no small part.

Mitchell Schwarzer: The branch that was the most steadfast, that had the largest membership who supported ongoing union efforts was the Oakland branch under C.L. Dellums.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: The porters are credited with helping to found the Black middle class in America, as well as the modern civil rights movement. In 1941, they threaten a march on Washington to protest employment discrimination. This is more than 20 years before the March on Washington where Martin Luther King makes his “I have a dream” speech.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Schwarzer says the community organizing that continues in West Oakland today, groups like Moms 4 Housing, are part of a legacy started by the Brotherhood.

Mitchell Schwarzer: If you look at Oakland’s history of civil rights activism, this is really the kind of start, you know. You think about the occupy movement in the 2010s, and the Black panthers in the 60s and 70s. It all goes back to the brotherhood of sleeping car porters.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: These railroad jobs were the foundation for a neighborhood of black owned businesses, nightclubs, and homes in West Oakland. Alan Laird remembers going to the porters union hall with his father and seeing a flourishing community.

Alan Laird: So in that community, we had all our own businesses and finances. I remember my barber shop, Stovall Barber Shop, was right there on Seventh Street. It was vibrant. It was people walking on both sides of the street going and coming with shopping bags and different things.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: West Oakland, and the 16th Street Station, were thriving. But all that starts to change in the late 1950s. The construction of the 880 freeway and later, the BART line, demolished a lot of those West Oakland businesses. And as the economy of West Oakland begins to decline, so does the 16th street station. The golden age of railroads comes to an end. Cars and airplanes become more popular and all those streetcars and suburban trains ceased to exist. By the late 80’s, just a few trains a day stopped at 16th Street Station.

Alan Laird remembers seeing the station in disrepair.

Alan Laird: When I pass by and it’s just a hulk, with a million memories, you know, the windowpanes looked as though they’d been in steady tears. And say, “Won’t, they notice me can’t they see me don’t they know who I was,” you know?

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: In 1989 the Loma Prieta Earthquake badly damaged the structure of the station, and it was closed. The last train rolled past it in 1994.

The station sat vacant and abandoned for 11 years. People squatted in it, covered it in graffiti, and stripped the interior. In 2005 it was bought by BRIDGE housing, an non-profit affordable housing developer. They wanted to turn the station into something the community could use, but like other redevelopment plans in West Oakland…

Jim Mather: A lot of those plans have been derailed by at least two major recessions during that time. I mean, the dot com bust was one, then the big recession.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: That’s Jim Mather, the Chief Investment Officer for BRIDGE. I met him outside the station. He says those recessions dried up a lot of the funding that the station needed. And the price tag for the restoration and seismic retrofitting the station needs is at least $50 million dollars. So the station is in limbo.

Jim Mather: We’re on hold. I mean, it’s really trying to find the financing. Any billionaires listening who want to want a project here, here it is.

Frankie Whitman: I like to say we’re looking for, uh, somebody with deep pockets who says, this is my legacy to Oakland.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Also here is, Frankie Whitman a consultant for BRIDGE. We’re going to go inside the station, for a chance to peek at some history most Oaklander’s never get to see. So I brought someone along who knows the station firsthand.

Recordings outside the station:

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Hey, nice to meet you, man.

Lamar MacDaniel: Hey, Am I late?

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: No, you’re right on time. Perfect timing. So welcome back.

Lamar MacDaniel: Alright alright

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: How’s it feel to be back?

Lamar MacDaniel: Oh man, I just got a little chill.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: This is Lamar MacDaniel. He started working out of the station in 1973. He’s 71 now. He walks a bit slowly, which he credits to working on the railroad.

Lamar MacDaniel: By the time you leave the railroad, walking on the train, serving, waiting tables and taking all that rocking and rolling, You’d be wowed, you’ll feel like you’ve been in football game for the last 27 years.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: When he started, MacDaniel was trained by some of the last of the Pullman Porters to work on the railroads. He started as a waiter and worked his way up.

Lamar MacDaniel: And I was the one that got, you know, I got taught a lot. That’s how I ended up being a maitre’d, which was the job that a Black guy didn’t have during the Pullman days.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: He hasn’t been inside since the station was closed.

Sound of door being unlocked

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: But today we get to go in.

Sound of everyone “wow” as they enter the station

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: The inside is jaw dropping. The ceilings are 40 feet high, adorned with intricate plaster work. Golden light filters in through arched windows. MacDaniel remembers some of the same things that made Alan Laird’s eyes big as a kid …

Lamar MacDaniel: They used to have a guy over there that was shine shoes … and over in that corner was a snack stand.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: But the grand clocks and chandeliers that Alan Laird told me about are gone. Somethings off.

Frankie Whitman: But you could even see here, even though it looks very distressed, it’s very evenly distressed.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Since BRIDGE has owned the station, they’ve rented it out to companies like HBO and Netflix for TV and movies, and those companies have left a lot of their sets behind.

Frankie Whitman: All the wainscoting, the door treatment, the window treatment, the valances … those are not elevators cause there’s no second floor. All movie set.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: More than one music video has been filmed here as well. So in the same spot where porters once carried luggage, E-40 told us how to go dumb in the Tell Me When To Go Music video.

Clip from “Tell Me When To Go”

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Mumford and Son’s did a video here too, and it has hosted Burning Man inspired parties. But BRIDGE can’t even do that anymore.

Frankie Whitman: This, this, this is new

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Back in the main hall, Whitman points to a pile of debris on the floor.

In the train station:

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Where do you think that fell from?

Jim Mather: Right up there.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Wow. So the, the ceilings like actively crumbling, huh?

Jim Mather: Yes. Another reason we don’t have, I mean, it’s part of the liability thing. Why we not having events in here anymore.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: We walk out of the main hall, through a dark corridor, to the old baggage wing.

Lamar MacDaniel: I’m going to need my flashlight

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Yeah, it’s pretty dark here.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: The baggage wing is thick with history. There’s an old scale for weighing luggage, and a large rolling door where passengers used to wait for their things. The first elevated tracks west of the Mississippi are directly over our heads. I walk with Lamar over to another small room. It’s the utility room, where the porters would hang out between shifts.

Lamar MacDaniel: There would be luggage all over the place. Guys would be here, when there wasn’t a train to be ready to be serving. The red caps would just hang out, back here and shoot the breeze, tell jokes and all kinds of stuff.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Some people want the station turned into a museum for the railroad and the porters, others want it to be an event space. Jim Mather from Bridge.

Jim Mather: Whatever happens here, BRIDGE is going to recognize and honor the history behind the station and its significance to the African-American community of Oakland.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Just When the doors of the 16th Street Station will reopen again is unclear.

Sound of freeway

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: To complete the tour we walk out to the back of the station.

Where once there was the shore of the bay, there’s the 880 freeway. Instead of trains, semi’s run in and out of the Port of Oakland. There are no tracks connected to 16th Street Station anymore. They’ve been dug up and taken away. It’s reminiscent of how this station has been disconnected from Oakland, the building neglected, the history obscured. Alan Laird again.

Lamar MacDaniel: It was like losing a friend, you know, but, you see the shadow of it right there and you want to run and tell people: “I remember when that was a palace! And that was filled with thriving hearts and minds and souls and energy and hope was waiting for you as you got off the train.”

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: You’ll never hear a train pull into 16th Street Station again, but it’s still possible the station could have a new beginning, just like the people that passed through it all those years ago.

(music bridge)

Olivia Allen-Price: So, Azul, as we mentioned earlier this story first aired in 2022, and there have been some recent developments. What’s happening now?

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: So the big news is that the 16th Street Station has been added to the National Register of Historic Places. A non-profit group called the Oakland Heritage Alliance submitted the application for the station, which basically outlined the stations significance for three things; its importance to local transportation, its architectural significance, and its relation to C.L. Dellums, and that’s the labor organizer you heard about in this story. The station was one of the first places to be recognized for this newly created category within the register, that recognizes the history of African Americans in California. I spoke to Feleciai Favroth, whose the treasurer with the Oakland Heritage Alliance, about this, she said she was ecstatic.

Feleciai Favroth: This could be the key to make the station a viable rehab project.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: The Alliance is really hoping this will turn the tide in the battle to get the station repaired.

Olivia Allen-Price: Historic sites make me think the building is like going to get a fancy plaque that has a little bit of history written on it. But what does historic designation mean practically?

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: So yes there is a lot of notoriety and national recognition that comes with being added to the register, but a really big thing that’s tangible is that it also opens the station up to a 20% federal income tax credit. And a developer could use that towards restoration of the station. This has actually worked in the Bay Area before. Like say, have you ever been to the Fox Theater in Oakland?

Olivia Allen-Price: Oh yeah, I’ve seen some great shows there and I always marvel at the ceiling in that place …

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Yeah, well the Fox is on the National Register, and received a federal tax credit toward its rehabilitation, including that really nice ceiling. So advocates are hoping this will happen to the 16th Street Station as well. But again this is all still just theoretical. There’s no money that has been committed yet.

Olivia Allen-Price: So it’s not like the station is suddenly saved necessarily…

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: No. There still aren’t any plans to restore the station itself. And another change is that BRIDGE Housing no longer owns the station, they sold it to City Ventures, a housing developer based in San Francisco and Irvine in 2022.

City Ventures has submitted plans to the city of Oakland to build a 77-unit townhome-style development — called “Signal House” — on the area around the station, but there’s no plan to rehabilitate the station itself.

To that end, City Ventures has hired a consulting group called OE Consulting to explore finding someone or some group to fund the rehabilitation of the station, separate from this housing project. They’re still trying to find someone to fund that. And even what the space could become is still open ended. Members of the Oakland Heritage Alliance have suggested a business incubator, or an events space, and something that highlights the history of the station, but as of now, those are all just ideas.

Olivia Allen-Price: Alright. Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman, KQED Features Reporter – thank you.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: You’re welcome.

(Music bridge)

Olivia Allen-Price: If you want to see some pictures of 16th Street Station, including some from our tour inside, head to BayCurious.org. We’ll drop a link in the show notes too.

Special thanks to Dan Brekke and Paul Lancour for their help on this episode.

This episode was made by Katrina Schwartz, Sebastian Miño-Bucheli, Brendan Willard and me, Olivia Allen-Price. Additional engineering from Christopher Beale.

Bay Curious is produced at member-supported KQED in San Francisco.

I’m Olivia Allen-Price. Have a good one!