Update, 1 p.m. June 10: Activists and parents who have occupied an East Oakland elementary school for the last two weeks say they intend to stay there until the district agrees to either reopen the school or hand over control of the building to the community.

Parker Elementary School families and supporters took their fight to Wednesday’s school board meeting, making the case that the district’s move to shutter the school will hurt its students.

Azlinah Tambu, the parent of a Parker student, told board members that the district has reassigned Parker students to other schools that are located too far away from their homes.

“Most of our children walk to the school because they live all through these apartments, and now they’ll have to walk from 79th and MacArthur all the way to 98th and Plymouth,” she said. “These are gang-infested areas. There’s human trafficking going on out here. There’s shootings every day. Those are the real safety hazards that we’re talking here.”

Oakland Education Association President Keith Brown this week said his union is in full support of the occupation — despite complaints from some activists that union leadership could be doing more to show up and help at the site.

Parents, Brown said, are rightfully frustrated they’re not getting a clear response from the district.

“If [the district] would have made the decision to authentically engage with families such as the families of Parker, they would not be forced to take the action that they’re taking now,” he said.

Meanwhile, California’s Labor Commissioner’s Office is reviewing claims made by the union that the district violated an agreement promising to involve community members in its decisions to close schools. Those hearings resume Aug. 9.

Original post, May 28:

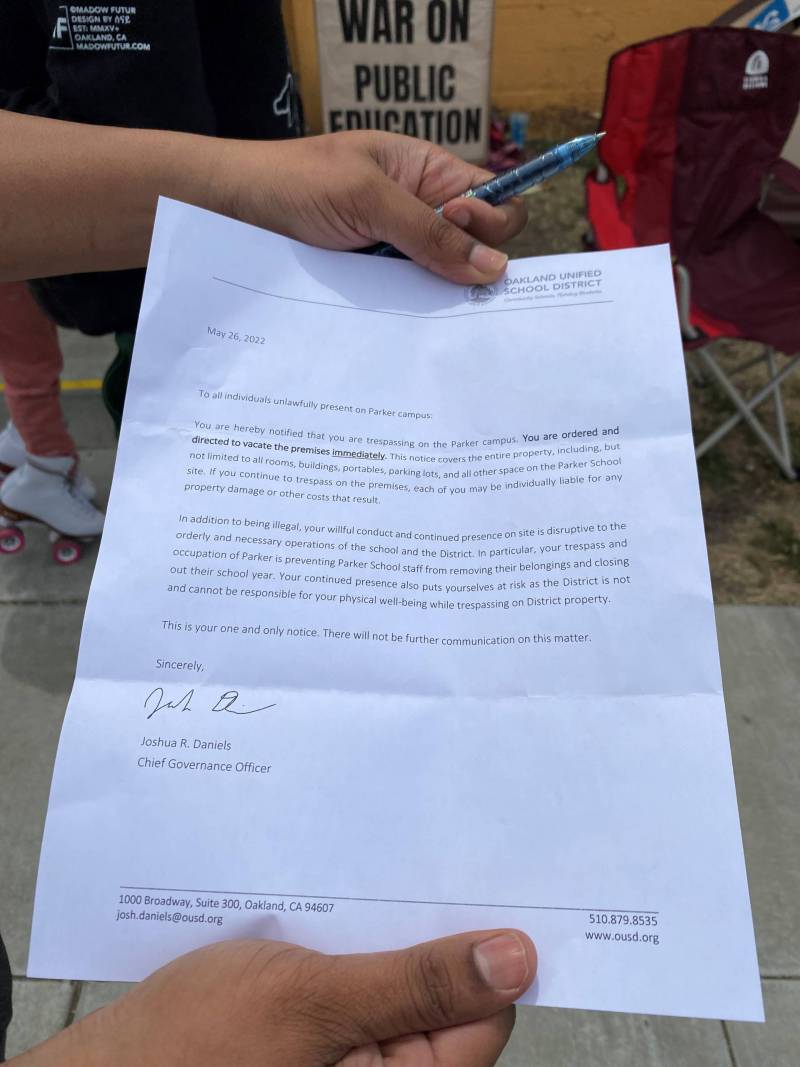

Parker Elementary in East Oakland was officially closed by the district on May 25, at the end of the school year, but families and activists have been sleeping in the auditorium since Thursday in an effort to reclaim the building for their own with a plan to begin a community school.

The activists say they will stay until the school board agrees to reverse its closure decision and fully fund Parker Community School, or give the community control of the building.

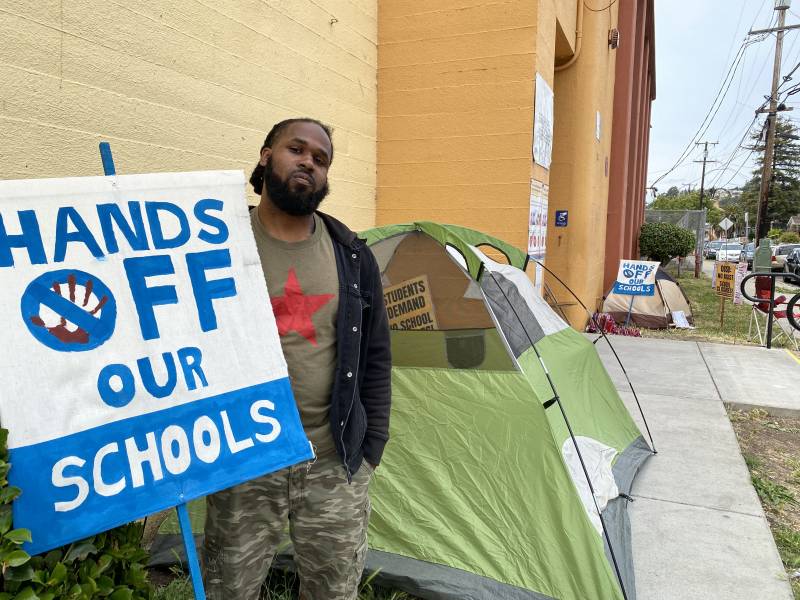

“Parents are liberating the school and want to keep it open and turn it into a real community resource to make sure it stays in the hands of the community,” said Timothy Killings, a caseworker at Westlake Middle School. He said GED classes, chess club and farm-to-table classes would be offered, with a celebration event planned for this weekend.