Just down from Hayward Regional Shoreline Park, is a power plant called “Calpine – Russell City Energy Center.” It’s the only thing still named for the town that was once here — a vibrant home to about 1,400 people. By all accounts it was the place to be on a Saturday night.

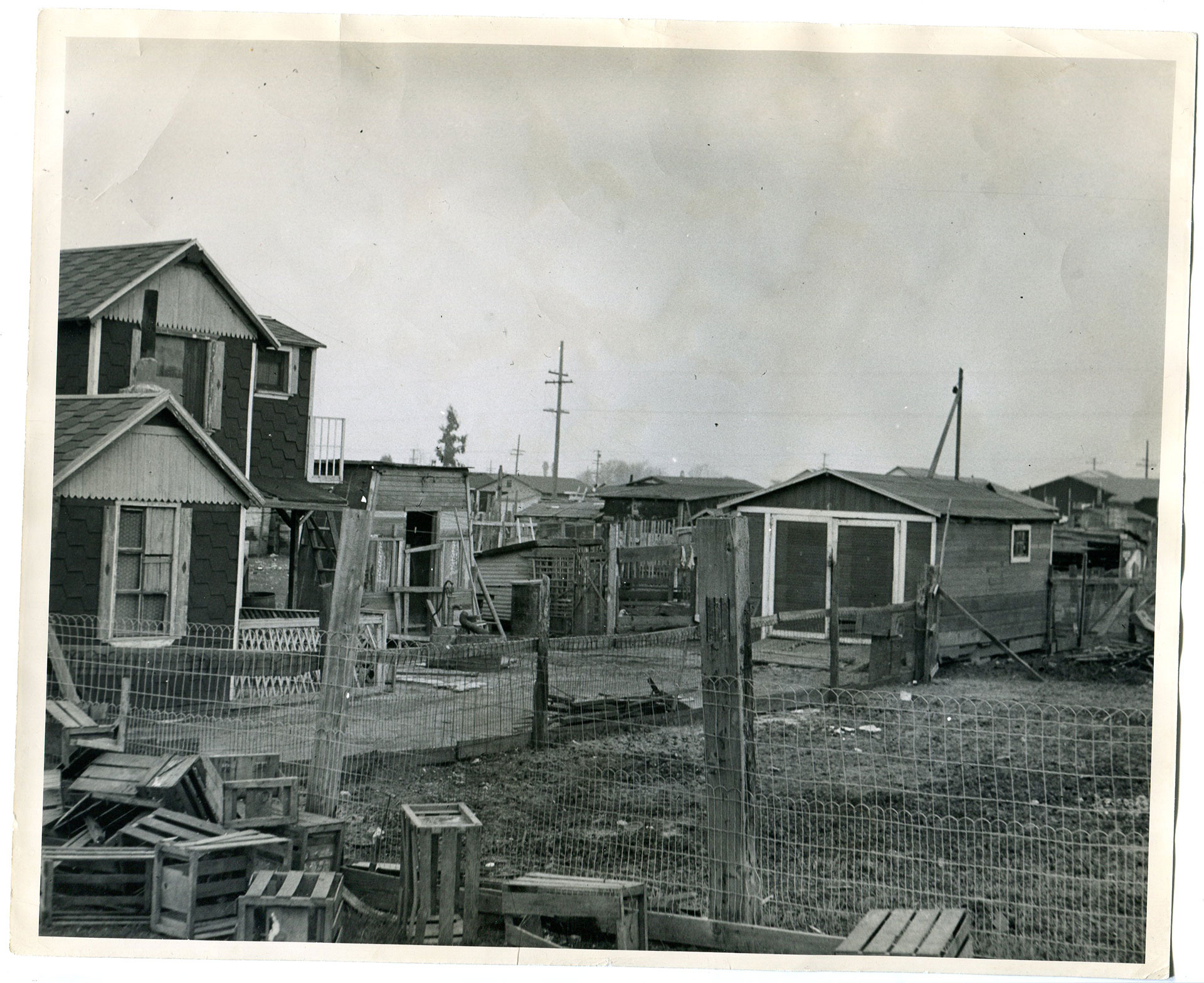

Named for a Gold Rush era teacher named Joel Russell, Russell City was founded in 1853, but it didn’t start booming until World War II when many people seeking work in nearby factories moved to town. Because Russell City was unincorporated, it became a haven for Black and Latino families who had difficulty buying property in other parts of the Bay Area due to racist real estate policies like racial covenants and redlining. In Russell City, there was room to build and people often tended a few animals and planted big gardens.

It was also home to several blues clubs and a thriving music scene. Famous musicians like Etta James, Ray Charles and John Lee Hooker played there, letting loose and enjoying the freedom of playing for Black audiences.

“Russell City people, they sang in church, they know harmonies,” explained Ronnie Stewart, Executive Director of West Coast Blues Society. Stewart didn’t grow up in Russell City, but he’s become obsessed with documenting its contribution to music history. “They know music. And (musicians would) go there because it’s a challenge. If you can get past Russell City, you can get past Carnegie Hall, you know.”

Former Russell City residents remember it as a loving place, but also one with deplorable living conditions. Because it was unincorporated, the town didn’t have any city services — no sewage, plumbing or electricity. Residents petitioned Alameda county and Hayward to bring these services to their community, but were repeatedly denied. Instead, the county used the conditions to declare Russell City “a blight,” justifying the use of eminent domain to seize properties and pay the owners far less for their land and homes than they were worth.