Before the Caldor Fire sparked one year ago this week — before its 150-foot flames devoured century-old ponderosa pines in California’s Sierra Nevada, and before it destroyed more than 400 of the 600 homes in Grizzly Flats — Mark Almer had a plan.

The 60-year-old retired fire inspector had spent over a decade fireproofing his Grizzly Flats home, trading wood deck boards for composite material and replacing traditional siding with a protective cement shell.

“Hardening the home is huge,” he said. “But it’s just one piece of the puzzle.”

Almer had an even bigger plan to protect his community.

For more than a decade, he’s led the Grizzly Flats Fire Safe Council, a group of two-dozen volunteers that raised money for wildfire mitigation projects, educated the town’s roughly 1,400 residents about defensible space and regularly gathered local, state and federal fire officials to help improve their fire response plan.

The Caldor Fire would be the council’s ultimate test.

On August 16, 2021, two days after the fire ignited, gusty winds pushed the flames out like billowing sails, spreading across thousands of acres overloaded with shrubs and trees in the neighboring Eldorado National Forest.

Almer and his wife didn’t grab much on their way out the door. Their six cats, corralled into six crates, took up most of the car space.

He was more concerned about making sure everyone else in the community got out safely. Before the official evacuation order came, Almer called his next door neighbor, Victor Diaz.

“I thought we still had time,” Diaz said in a recent interview.

But Almer’s voice indicated otherwise. An even-keeled speaker with a clean vocabulary, Almer barked his warning with a rare four-letter word that Diaz declined to repeat.

“You need to get the beep out,” Diaz recalled.

Diaz, his wife, their six kids and the family dog raced down Grizzly Flat Road in a two-car caravan, leaving behind the fire’s red glow and the home they’d never see again.

Many residents knew this day might come. At a community meeting in the early 2000s, the U.S. Forest Service, with chilling foresight, had warned that a wildfire mirroring the Caldor Fire’s burn progression could easily wipe Grizzly Flats off the map.

In the years that followed, the Forest Service took steps to prevent such a catastrophe. But a nine-month investigation by CapRadio and The California Newsroom, a public media collaboration, found that the Forest Service’s plan to protect Grizzly Flats fell far short:

- After the community meeting, the Forest Service took a decade to announce a comprehensive 15,000-acre forest management and fire mitigation plan, called the Trestle Forest Health Project. It aimed to “reduce the threat of large high intensity wildfire and threats to Grizzly Flat[s]” and other nearby landowners by removing excess brush and vegetation that fuel increasingly devastating wildfires, according to project documents.

- The Forest Service originally committed to finishing the Trestle Project by 2020 — a year before the Caldor Fire would later ignite. Due to a complex web of regulatory delays, logistical challenges and resource shortages, the agency pushed back the completion date to as late as 2032 — three decades after its initial warning to Grizzly Flats.

- The Forest Service’s data overstated Trestle Project accomplishments, claiming the agency completed work on at least 24% of the project before the Caldor Fire. Original analysis of corrected Forest Service data provided by the agency shows only 14% completion. The agency confirmed the inaccurate information had been online for more than a month; it updated its database less than a week before publication of this story.

- The corrected data also suggests that in the decade-and-a-half leading up to the Caldor Fire, the Forest Service completed 15,000 acres of fuel reduction work within a five-mile buffer around Grizzly Flats — coincidentally, the same number of planned acres in the Trestle Project. However, the actual coverage of that work was limited to 5,800 acres because of the agency’s decades-long and highly criticized practice of counting repeat treatments on the same parcel. Furthermore, the majority of that work occurred several miles from the town’s border.

- The Forest Service failed to complete sections of the Trestle Project along the southern border of Grizzly Flats, identified as “first priority” due to the area’s susceptibility to wildfire. Instead, the agency prioritized removing trees — often far from the town’s borders and not a part of the “first priority” area — that generate revenue.

- Despite more than five requests, the Forest Service failed to provide complete data on its national wildland fire management budget, citing a recent data transfer in which it lost some information from the past two decades. The agency also could not provide similar budget information at the regional and forest level, saying numerous changes to the budget structure and process over the last 20 years made retrieving the data especially difficult and would render any analysis “incomparable.”

Agency leaders say a slew of hurdles stood in the way of the project’s completion: limited funding, pushback from environmentalists and fewer opportunities to complete essential prescribed burns due to staff shortages and climate change.

“I am committed to doing everything I possibly can to mitigate [wildfire risks] on our landscapes,” said Forest Service Chief Randy Moore in an interview.

When asked if his agency bears any responsibility for the devastation in Grizzly Flats as a result of the stalled Trestle Project, he cited financial constraints.

“I mean, do[es] anybody bear any responsibility for not having the budget to do the work that we need to do?”

The Eldorado National Forest falls under the Forest Service’s Pacific Southwest Region, which Moore led from 2007 to July 2021, when he was appointed chief by President Joe Biden’s administration. He assumed office just a few weeks before the Caldor Fire ignited. Moore declined multiple opportunities to say whether completing the Trestle Project would have resulted in a different outcome in Grizzly Flats.

“I’m not really sure why we keep talking about that question,” he said.

After reviewing this investigation’s findings, a dozen sources — including wildfire experts, career firefighters, former Forest Service officials and residents — said they believe Grizzly Flats would have stood a better chance of surviving the Caldor Fire if the Trestle Project had been completed.

Among the sources was one of the project’s key architects, former Eldorado National Forest District Ranger Duane Nelson.

“There would have been a very high probability that Grizzly Flats would not have burned in the Caldor Fire” if the Forest Service completed the Trestle Project, Nelson, 67, said in an interview. “It could’ve meant survival.”

An early warning

On a chilly day this past March, Almer sat in his idling white Toyota Tundra pickup next to where the Grizzly Flats Community Church once stood. The small yellow chapel bordered by white picket fencing had vanished, along with most of the community, in the Caldor Fire’s wake. From the driver’s seat, Almer observed rows of charred metal chairs facing an absent pulpit.

“It’s kind of eerie,” he remarked, “as if they were still ready to accept parishioners.”

The church is where local Forest Service officials, in the early 2000s, held their town meeting to warn residents about wildfires. Grizzly Flats is surrounded on three sides by the Eldorado National Forest; the agency acknowledged that a devastating fire would likely rip across federal land before reaching town. Using a PowerPoint to show fire modeling scenarios, they gamed out all the ways Grizzly Flats could go up in smoke.

“It was important for us to start talking to people and make sure that they had the information that we had about what our models were showing,” said Kathy Hardy, a former district ranger who attended the meeting.

One scenario showed what would happen if the fire started a few miles south of town in the Eldorado National Forest, close to where the Caldor Fire would ignite years later.

“The modeling said that it would take out Grizzly Flats within about 24 hours,” Almer recently recalled. “Well, 20 years later, that’s pretty much exactly what happened.”

The Forest Service has not provided records related to the meeting in response to a Freedom of Information Act request filed in December 2021.

As Forest Service officials flipped through presentation slides, residents shifted uncomfortably in their metal chairs. This was a town that had just installed its first all-way stop sign. The Grizzly Pines School had recently earned a Distinguished School Award from the California Department of Education despite having only 36 students. The place, in many ways, was idyllic — so remotely located and so small that it had no grocery store, no gas station, no diner, not even a local bar. Now, the Forest Service was telling them, with data to back it up, that their town and their lives sat in Mother Nature’s crosshairs.

Two fire plans, two timelines

Grizzly Flats wasn’t the only town in peril. For years, the federal government had been wringing its hands over the nation’s growing wildfire crisis. In 2000, wildfires burned over 7 million acres across the country — a stunning total at the time, and a harbinger for even worse years to come.

In response, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Department of the Interior — the agencies that managed much of the land that had been scorched — developed a National Fire Plan. It emphasized forest management and fuel reduction as key preventive measures. Methods traditionally used by the federal government include commercial thinning (cutting some trees to be sold as timber or wood pellets), removing brush with heavy machinery (a process known as mastication), and prescribed burning (intentionally setting lower-intensity fires that benefit the landscape).

To figure out where to put its resources, the Forest Service — which operates under the USDA — helped compile a list of communities nationwide at “high risk from wildfire.” It included thousands of communities, identified primarily for being in the “wildland-urban interface” or WUI, a term used to describe the intersection of developed land and the natural environment.

Buried on the list was “Grizzly Flat.”

(The town, throughout history, has been referred to as “Grizzly Flat” and “Grizzly Flats.” The latter is more common.)

Shortly after the Forest Service’s cautionary meeting at the local church, Almer and two-dozen other residents formed the Grizzly Flats Fire Safe Council. They set up an informational phone line, installed a nine-foot community bulletin board at the post office and started an adopt-a-hydrant program, which got residents to shovel out hydrants after snowstorms.

The council served as an essential community thread in the simple quilt of Grizzly Flats.

“There was no government, there was no mayor,” said Kathy Melvin, 78, who joined the council in 2007. “There was just the fire safe council, the church and the school. Everything kind of revolved around those entities because we didn’t have anything else.”

Within a couple years of its founding, the council commissioned its own community wildfire protection plan. The 74-page document laid out plans to clear evacuation routes and assist residents with defensible space around homes.

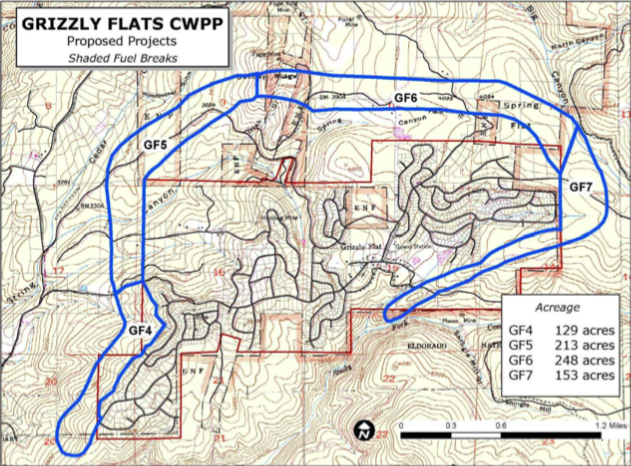

It also proposed a series of fuel-reduction projects, including an ambitious “shaded fuel break” in the shape of a horseshoe around Grizzly Flats. Shaded fuel breaks remove ground vegetation to reduce wildfire intensity and provide a staging area for firefighters. The horseshoe covered the east, north and west sides of town; the community was banking on the Forest Service to tackle fuel reduction work along the southern border to complete the protective buffer.

The plan would cost millions of dollars, and the council raised money however it could. An area couple hosted 150 people at their home for a wine tasting under paper lanterns and summer stars. The council held annual barbecues. What money it couldn’t raise, it made up for with grants.

The efforts paid off. Over the next 15 years, the fire safe council cleared more than 1,500 acres of fire-prone vegetation around town, completing almost all of the horseshoe fuel break at a cost of nearly $2 million. The council even earned national recognition for its productivity and wildfire mitigation work.

Meanwhile, most of the Forest Service land to the south of Grizzly Flats remained dense and overgrown — a reminder to residents that their community was dangerously exposed.

‘Big, hairy, audacious goal’

As a district ranger in the Eldorado National Forest, Duane Nelson started each day with a clean, pressed uniform and aimed to clock out with dirty shirtsleeves and muddy boots.

“I wasn’t going to just be a ranger sitting in the office behind a computer all the time,” he said. “I made a promise to myself that I would be out looking at projects, checking up on crews or going by fire stations.”