This story comes to us as part of a collaboration with Civil Eats, a daily news source for critical thought about the American food system.

For much of my 20s, I fantasized about working on a farm. I’d wake up with the birds and spend most of my time outdoors, learning about the basics like soil composition, pest management and tractor safety. The plants themselves would teach the more conceptual subjects, on tenacity and growth. This version of myself would be more attuned to nature and to herself — the kind of knowing that I imagined could only come from true solitude, away from technology and the white noise of everyday life. The farm would be my “Walden.”

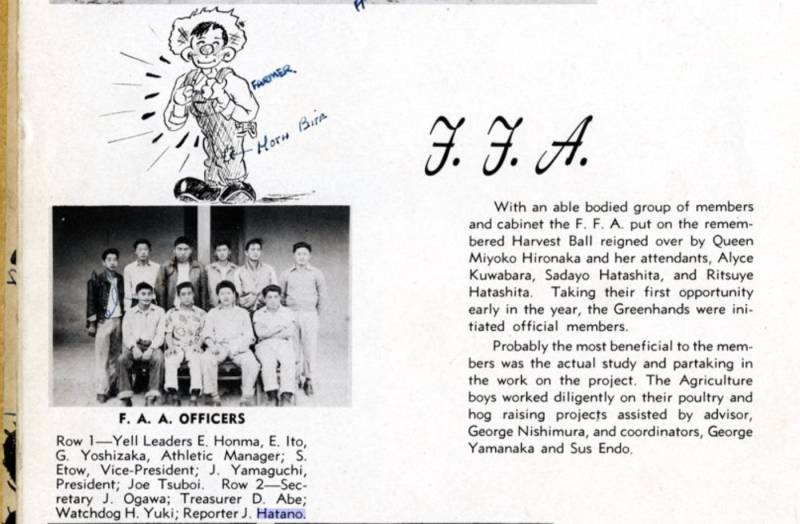

I didn’t realize it then, but my daydreaming wasn’t just a coping mechanism — it was largely a yearning for connection with my Japanese heritage, and the side of my family I share it with. They’d been farming in California since immigrating, and, when I was growing up, our relationship had mostly boiled down to annual pleasantries (not including my bachan, my grandma, who attended all of my horse shows and volleyball games with a bag of salty Tengu beef jerky in hand).

It wasn’t until last year, on the brink of turning 30, that I finally got the nerve to hit pause on the college-to-corporate-America pipeline to work on a vegetable farm just outside Boston. At my 9-to-5 job, I’d been a senior editor at a small content agency. On the farm, I was just another Carhartt-clad apprentice plastering bandages on my tender, cracked hands. Each week, we’d seed new plants in the greenhouse, transplant and maintain seedlings in the fields, harvest as fast as we could, and pack boxes for the weekly CSA (community-supported agriculture) in an assembly line, with someone’s playlist setting the pace.

Before I ever even touched a harvest knife, I knew my favorite crop would be sunflowers. And sure enough, every time I worked my way down a towering row, tilting each flower’s belly down to check how many petals had popped, stumbling out of the field with as many as I could sling across each arm, infant-style, I was reminded of my jichan — my grandpa.

Some 70 years ago, he had sized up his newly leased plot of land and decided to gamble on the very same flower. His farm was across the country in Rancho Palos Verdes, California, a coastal Los Angeles suburb that looks like a California tourism poster, with dramatic rolling hills and cliffs to match. When he died in 2015, just a year after retiring, I had a kind of awakening, realizing I’d missed my opportunity to connect with him in any kind of meaningful adult way.

Not long after I wrapped up my apprenticeship and moved to Brooklyn, I learned that his farm, which had continued to operate under his longtime foreman, would soon be forced to close. Like many farmers in the U.S., he’d rented his land, and under pressure from the National Park Service, the city of Rancho Palos Verdes was terminating the lease. It would have meant the end of an era for my family regardless, but his farm also happens to hold a larger, more significant legacy: It’s the last Japanese American-founded farm on a peninsula that was once home to hundreds of them — and on Aug. 16, 2022, it ceased to exist.

I grew up hearing stories about what the peninsula used to be like, back when it was crowded with strawberry and garbanzo bean farms run by Japanese Americans, and my dad would go pigeon hunting with the rest of the farm kids as a method of pest control. Now the area is home to a Trump golf course, a luxury coastal resort and neat rows of identical houses. That’s all thanks to the Japanese American community, which first leased the land in 1882 and transformed it from desert into fertile farmland. Together, many of the farmers pioneered dry-farming techniques that are still in use today, and increasingly important as California’s climate grows increasingly arid.

I’ve since learned that a similar story played out up and down the West Coast, despite Japanese immigrants not being able to legally own agricultural land in California until 1952. By the 1910s, nearly two-thirds of residents with Japanese ancestry on the West Coast worked in farming. And they were incredibly successful at it — the average value per acre was $280 for Japanese farms, versus an average $38 for all West Coast farms. In Los Angeles County, where my jichan raised sunflowers and baby’s breath, Japanese American farmers generated $16 million of the $25 million flower market business.

It makes sense, then, that in 1942, when 120,000 Japanese people on the West Coast (the vast majority of whom were American citizens) were incarcerated in concentration camps following Executive Order 9066, white growers were the ones who benefited from commodity price spikes due to shortages. And it’s no coincidence that today, white landowners still control an estimated 98% of farmland in the U.S. I was reminded of this fact every time I toured another organic farm last summer — each grew the same things, used the same tools, shared the same foundational history.

In the subsequent years of incarceration, many Japanese Americans lost their land, had their equipment stolen, and were forced into agricultural work at camps. Most never returned to their former agrarian lives. After the war, the U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that Japanese American farm ownership, including leases, dropped to less than a quarter of what it had been.

My jichan was incarcerated in the Poston, Arizona, camp as a teenager, eventually escaping by enlisting in the military. It wasn’t until the 1950s that he leased his peninsula plot from the military, which still controls 1.7 million acres of land in California. When the city of Rancho Palos Verdes was incorporated in 1973, part of the land-transfer agreement mandated that the parcel he was on be converted to recreational use.

Whether it was out of guilt, respect or plain-old bureaucratic disorganization, the city allowed my jichan to renew his lease anyway until 2014. That was the year he retired and transferred the lease to Martin Martinez, who had started working with him at the farm as a teenage immigrant from Mexico. Allowing his legacy to live on through Martinez would have been especially meaningful, as he represents another oppressed community that now forms the backbone of California agriculture.

When my jichan’s lease expires, with it will go our community’s only tangible tie to the land we nurtured and made viable, land that provided Japanese Americans with livelihoods, camaraderie and an anchor in times of great turbulence and terror. And although Rancho Palos Verdes is pursuing a historical designation with the intention of preserving that history in some way, it doesn’t feel equitable in any sense. A plaque doesn’t maintain a sense of place.

And this story isn’t singular, which naturally leads me to a string of what-ifs: If Executive Order 9066 had never been issued, if Japanese Americans didn’t suffer devastating economic setbacks as a result, if we didn’t continue to face discriminatory laws after the war ended, would my jichan have been able to buy land? Would property ownership alone have dramatically changed California’s agricultural landscape?

Of course, leasing farmland is still common practice today: In 2016, the USDA reported that more than half of cropland in the U.S. is rented. An inability to acquire land is one of the biggest barriers to entry for new farmers, and because many white families already own farmland or other land they can sell to acquire it, farming remains a predominantly white industry. Like many things in this country, the hierarchy — with white landowners at the top and immigrant laborers at the bottom — stays intact by structural design.

Before I started my apprenticeship, I wondered if one season of farming would be enough to fulfill my agrarian fantasy. Now, a full year out, I find myself mentally drifting back to the easy routine of last summer — of spending all day with my hands in the dirt, playing Marco Polo in the sunflower fields, driving home in silence with the windows down, smelling like sweat and tomato plants. I recognize in farming and gardening an opportunity to feed people, but also to build collective knowledge, establish traditions and honor shared history. And, eventually, I hope, to challenge the status quo.

One of the things I like most about farming is that you’re always building on your own work. Over time you create the kind of soil you want, and each season you review last year’s notes and make adjustments to improve yield. It’s a practice that rewards patience. In some ways, turning soil over is almost like burying our dead — cover crops and sunflower stalks become food for the next generation. Which means that long after you’ve left land behind, there’s always evidence you were there.

My jichan’s farm might no longer exist in name after this month, but in every plant that blooms up and down the peninsula, there will be a small piece of him and the community he belonged to. And that’s something no one can take away.