At least 400 people turned out to Embarcadero Plaza in San Francisco on Friday evening to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the cycling event known as Critical Mass.

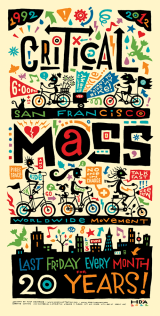

At its simplest, Critical Mass is a group bicycle ride. But it has also been called an “organized coincidence” or a “leaderless phenomenon.” That’s because for the last 30 years, on the last Friday of every month, hundreds and sometimes thousands of cyclists have participated in a ride that has no leadership, organization or planned route to speak of.

Originally called the “Commute Clot,” the ride began in September 1992 when a group of about 50 friends decided to ride home together after work on a Friday.

“Why don't we just get together at the end of the day and ride home together as a way of promoting our own collective experience of bicycling in extremely hostile conditions?” said Chris Carlsson, one of the cyclists who participated in the original ride.

Cycling in San Francisco in the early 90s was a far cry from the protected bike lanes and hordes of bicycle commuters found on city streets today.

“We were so angry because you weren't allowed to bicycle in San Francisco in the early 90s. I mean, you certainly could do it, it was legal, but you were taking your life into your own hands.” said Dave Snyder, another cyclist who participated in the original ride. “It was our way of collectively asserting our rights.”

Over the years, the ride gained popularity in San Francisco. Snyder estimates that over 5,000 people attended a Critical Mass ride in 1996. The ride also spread to other cities.

“When it started to spread to other cities right away, we knew that it was something much bigger than we had initially intended,” said Hugh D’Andrade, another original Critical Mass rider.

Chris Carlsson estimates that Critical Mass events now take place in over 400 cities across the world.

As Critical Mass grew, so did the attention it got from local politicians. In 1997, then-Mayor Willie Brown famously ordered the police to crack down on the event after thousands of cyclists snarled traffic in city streets.

Dave Snyder, who was executive director of the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition at the time, said this moment in Critical Mass’ history produced an inflection point where membership in the Bicycle Coalition soared, and politicians realized they needed to heed calls for better bicycle infrastructure in the city.

“That was when the city had to take seriously what the Bicycle Coalition had been asking it to do for a long time,” said Snyder.

“It was really interesting when Willie Brown cracked down on Critical Mass. It just caused all the bicyclists to come out in support of our movement. Thanks Willie Brown,” said Hugh D’Andrade.

Critical Mass has received criticism over the years for instances where participants have acted aggressively and violently toward motorists. Cyclist Chris Carlsson says these people are a minority, and characterizes them as the “testosterone brigade.” He says it’s the same bad apples that are present at any public event, but it isn’t what the ride was intended to be, and it’s something the original riders say they fought against in the early years.