If you attended public elementary school in California, you probably remember a popular fourth grade social studies assignment: build a model of a California mission, using popsicle sticks, sugar cubes or clay to mimic the adobe bricks and chapel bell towers.

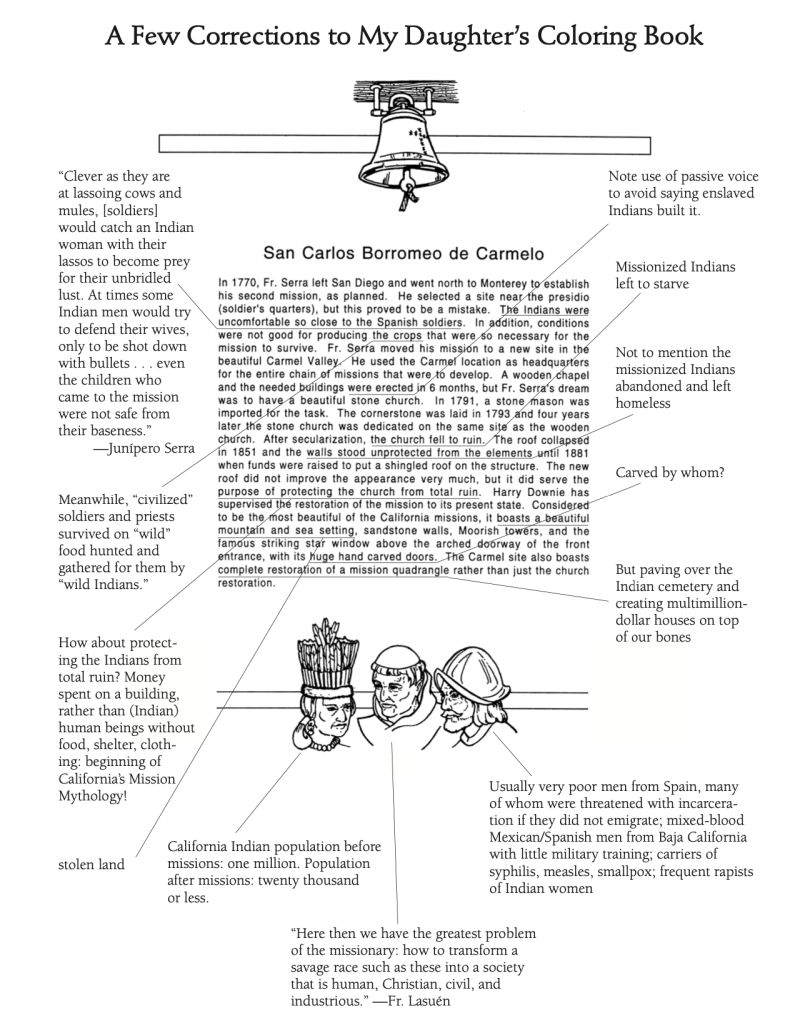

In her groundbreaking 2013 book, Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir, poet Deborah A. Miranda argued those missions were built on enslavement and forced labor. They were places where her ancestors had little choice but to work, and where they endured brutal punishment and exposure to disease in order to enrich the Spanish empire. So she turned that elementary school assignment on its head.

“What if children were asked to build a model of a Southern plantation with people in the fields being whipped, or a concentration camp model with enslaved Jews being pushed into ovens?” asks Miranda, echoing a challenge she presents in the book.

“What if those lessons were presented in the same way California Indigenous people are presented? As something of the past, something of a curiosity, something that a fourth grader could easily research and write a report and build a model of? I think that by framing it this way as a thought experiment, it has jolted a lot of readers.”

Miranda is an award-winning poet, writer and professor and an enrolled member of the Ohlone/Costanoan-Esselen Nation of the Greater Monterey Bay Area, with Santa Ynez Chumash ancestry. Bad Indians, which has just been released as an expanded 10th anniversary edition, explores the history of Central Coast tribes through the records of Miranda’s own ancestors, including wax-cylinder recordings dating back more than a century. She also draws on the treasures she discovered in listening to a garbage bag full of cassette tapes from her grandfather, Tom Miranda, who hid his regalia and love of traditional dance in an era when many California Indians tried to assimilate or mask their Indigenous heritage.

The 10th anniversary edition features a rich array of drawings, poems, newspaper clippings, photos and prose, as well as sample “mock” lesson plans that challenge the fourth grade mission-building assignment — which, due in part to Miranda’s scathing critique, has largely been made optional in California public schools.

Other new additions include essays and poems about the 2015 canonization of Father Junipero Serra, the Spanish priest known as the “Father of California Missions.” Miranda and other California Indians were active in protesting the Catholic Church’s decision to make him an official saint.