The Golden Gate Bridge. The Bay Bridge. Sutro Tower. Coit Tower. Perhaps even (whisper it) the Salesforce Tower.

When it comes to instantly recognizable structures, San Francisco suffers no shortage. But if asked to pick their favorite, many people might go for a classic: the Transamerica Pyramid.

The Pyramid — officially known as the Transamerica Pyramid Center — first opened back in 1972, making it a half-century old this year. At over 850 feet high, back then it was the tallest building San Francisco had ever seen. It has over 3,000 windows, an exterior of white quartz, and an illuminated spire at its very top, like the star on top of a Christmas tree.

The Pyramid is no longer the tallest building in San Francisco; that honor now goes to the Salesforce Tower, at 1,070 feet. But even as this building officially turns 50 years old — the same age as The Godfather, the Honda Civic, Pong, and Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson — the story of how it came to be might surprise you.

That’s because what is now an architectural icon was once quite controversial.

San Francisco before the Pyramid

Like a pin in a map, the Transamerica Pyramid marks the spot where the communities of Chinatown, North Beach, Telegraph Hill and the Financial District converge. And historically speaking, the Pyramid is built on hallowed ground.

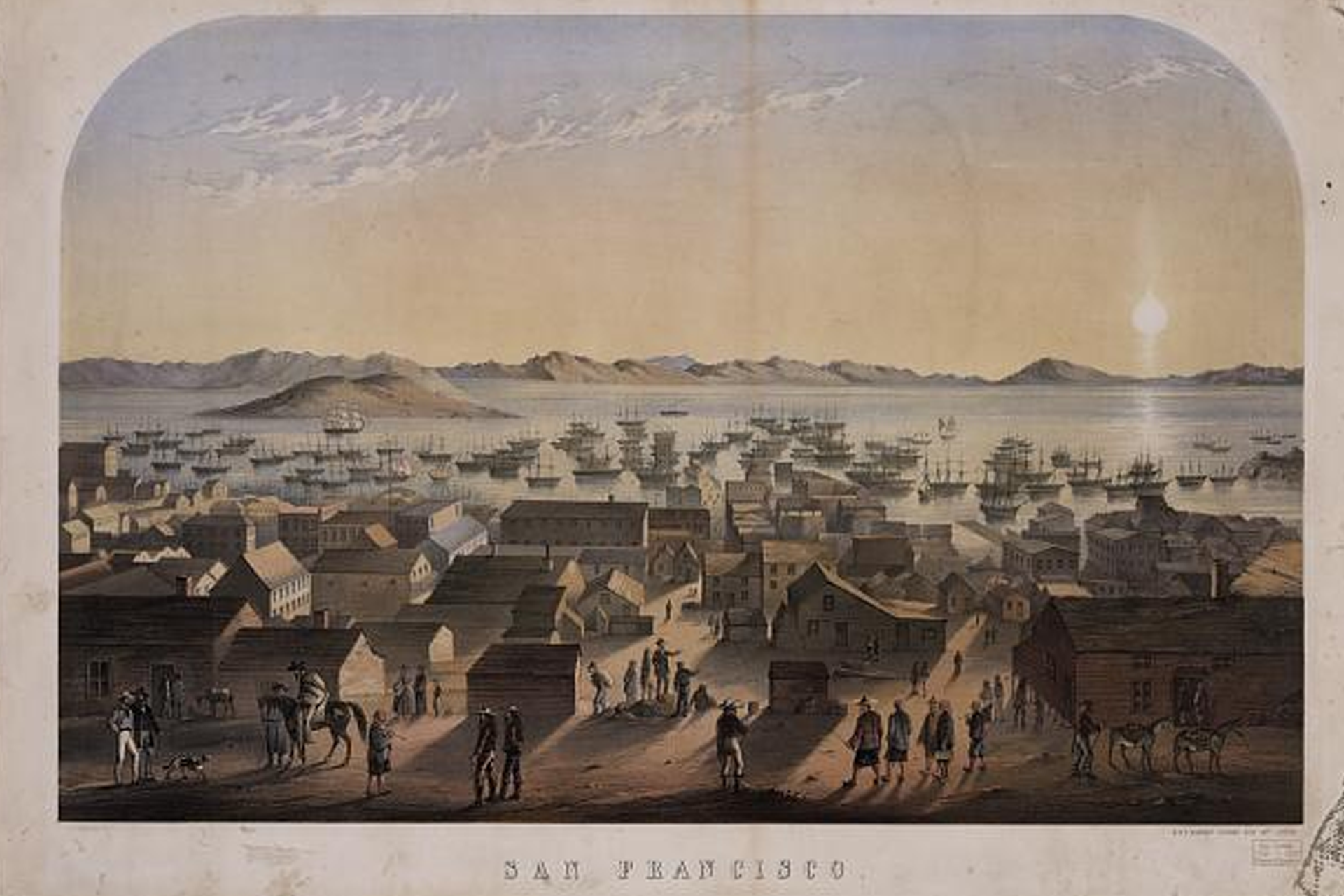

In the first half of the 19th century, this area of San Francisco wasn’t several blocks away from the bay, like it is now. It was the Barbary Coast, right on the water. A whaling ship called the Niantic even ran aground here in 1849 after the crew jumped ship to make their fortunes in the gold fields. Like many ships around this time, instead of being removed or torn down, the Niantic was instead absorbed into the fabric of the city: It was retrofitted into a hotel and ultimately became part of the landfill as the city expanded into the bay.

Back during the Gold Rush, Montgomery Street was at the center of city life. In 1853, workers constructed a massive building — appropriately known as the Montgomery Block — on the exact spot where the Transamerica Pyramid would later be built. “At the time, it was the tallest building west of the Mississippi at a towering four stories,” said author Hiya Swanhuyser, who is currently writing a book about the history of the building. “[It was] built, famously, on a foundation made up of redwood logs interlaced that were floated across the bay.”

San Franciscans, Swanhuyser says, even called the Montgomery Block “a floating fortress.”

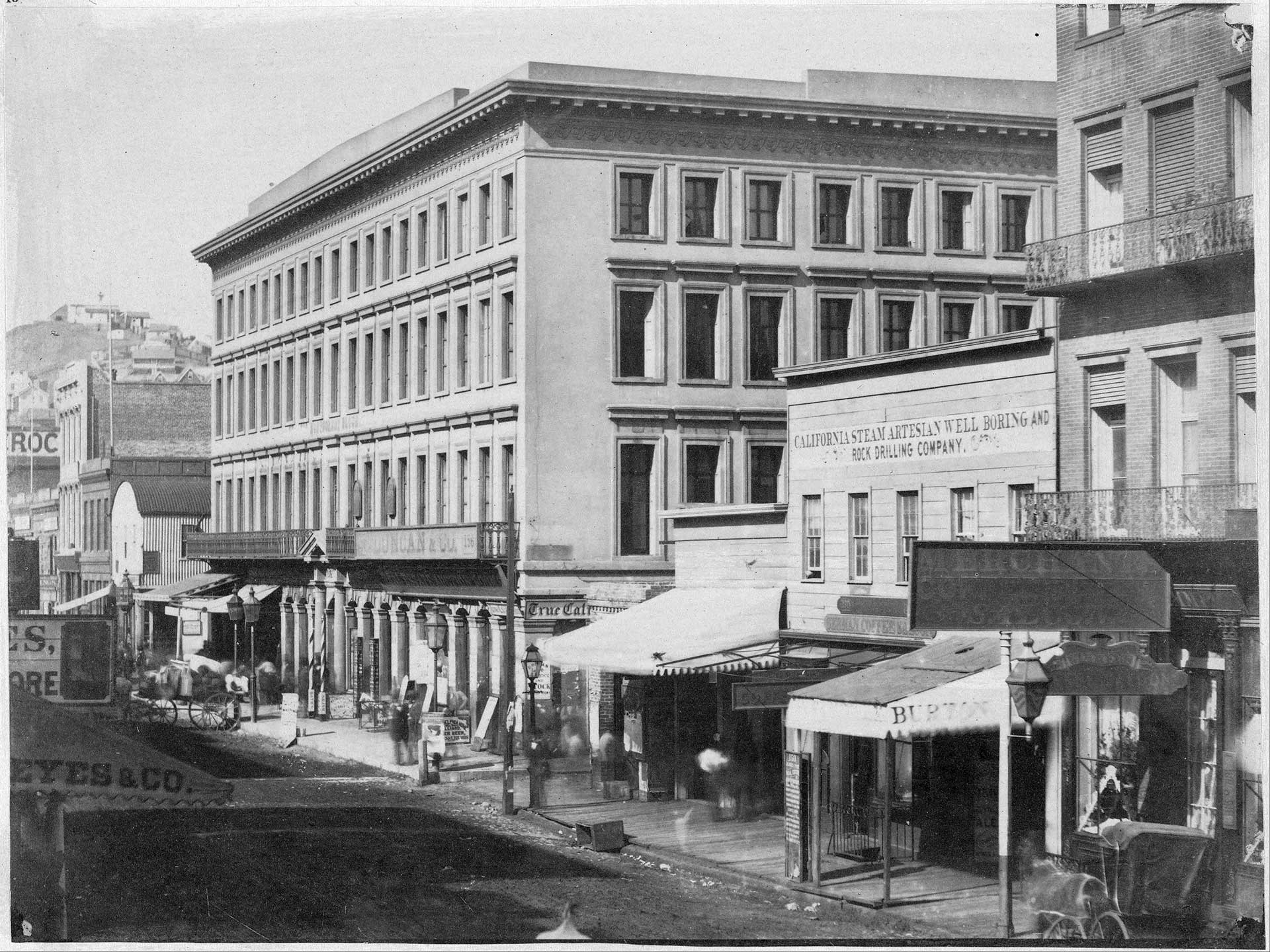

Like so many spaces through San Francisco’s history, the Block — and the people inside it — lived many lives. Originally, the space was built to be law offices and a hangout spot for San Francisco’s high society. But when the city’s business folk started to migrate south to Market Street, artists moved in. The Montgomery Block entered its creative era.

“They were writers and sculptors,” said Swanhuyser, “people who were inventing journalism in the mid-1860s. People like Ambrose Bierce, who, according to some, was America’s first newspaper columnist, and Mark Twain and Bret Harte. And Ina Coolbrith, who was California’s first poet laureate.”

This area of Montgomery Street was known for its bohemian ways, a scene that attracted freethinkers from near and far. Just a block to the north, now-iconic artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera lived and worked here in the 1930s. But the Montgomery Block’s influence was also ideological, says Swanhuyser, a “hotbed of painters and political people”: The massive General Strike of 1934, which shut the city down for four days and brought class struggles to a head, was organized, in part, right here.

The lights went out on the Montgomery Block’s creative chapter in 1959. That year, explained Swanhuyser, “a man named S.E. Onorato bought it and tore it down, claiming he was going to make a parking structure.” But Onorato never got to build his parking garage, and the space remained a single parking lot for almost a decade.

That’s when the Transamerica Corporation — and the Pyramid — came into the picture.

Path to the Pyramid

Transamerica is now a financial services company, concerned with insurance and investments. Its story starts back in 1904 with the founding of the Bank of Italy in San Francisco — the brainchild of San José’s A.P. Giannini. That bank would become the Bank of America in the 1930s.

Transamerica began as the holding company for Giannini’s various financial ventures, which had by then become legion. The original “Transamerica Building” is actually still standing — it’s that flatiron-looking building that forms a junction between Montgomery Street and Columbus Avenue, just across the street from where the Pyramid now stretches into the sky.

Now it’s the San Francisco headquarters of the Church of Scientology, but in 1969, it was home to the corporation that wanted a new headquarters. And it turned out Transamerica wanted to build … a pyramid.

The corporation had brought in a Los Angeles architect named William Pereira who had worked as an art director in Hollywood. His brief was, apparently, to create something that allowed sunlight to filter down to ground level.

Pereira envisioned a pyramid more than 850 feet tall, with two wing-like columns running up either side to allow for an elevator shaft on one side and a stairwell on the other. Even with its pyramid structure, it would have a capacity of 763,000 square feet.

When the Transamerica Corporation shared the design with the public, the critics hated it. The San Francisco Chronicle’s architecture writer Allan Temko called it “authentic architectural butchery.”

And it wasn’t just local critics. The Washington Post said the Pyramid proposal was “a second-class World’s Fair Space Needle.” Los Angeles Times critic John Pastier called the design “antisocial architecture at its worst,” capturing a broader unease at how Transamerica was trying to smear its corporate vision on San Francisco’s skyline. “Corporations that are far more important to the city have exercised considerably more restraint in their architecture than Transamerica,” wrote Pastier, “which is blatantly attempting to put its ‘brand’ on the city.”

In 1969, San Franciscans protested against the Pyramid plans in the street, carrying signs that bore slogans like “Corporate Egotism” and “Stop the Shaft.” Some protesters even donned pyramid-shaped dunce hats. (You can see more photos from the protests in the San Francisco Chronicle’s archives.)

Those protesters included Hiya Swanhuyser’s mother. “She was a community-minded hippie and she didn’t think that a neighborhood was the right place for a skyscraper,” Swanhuyser said.

There was even a lawsuit filed by nearby residents. At a City Hall hearing about the proposal, an attorney for the Telegraph Hill Dwellers Association spoke for those residents, in language that echoed the burgeoning environmentalism of the 1960s.

“The curse of this country is the worship of material things,” the residents’ attorney told City Hall. “We’ve polluted our rivers, our harbors, and our lakes, and our air — and we’re now about to pollute the skyline of San Francisco, one of its greatest treasures.”