The authors said decision-makers should treat the research as a warning sign of what’s to come in a warming world. May said there are hundreds, if not thousands, of contaminated sites around the Bay — remnants of the region’s industrial past — and if groundwater rises, it could all come in contact with this pollution buried throughout the shoreline.

“Anytime you’re leaving contamination in the ground, if those conditions change, such as the water table is rising, that provides the potential to remobilize contaminants and create a new exposure pathway that could impact the environment or public health,” she said.

Risks of contaminants resurfacing disproportionately affect lower-income communities and communities of color because historical injustices mean that they are more likely to live near contaminated sites, said Kristina Hill, professor at UC Berkeley and a co-author of the report.

“Even a few inches of groundwater rise may mobilize contaminants or change flow directions, causing contaminants in the soil to spread,” she said. “Existing remediation plans don’t account for this.”

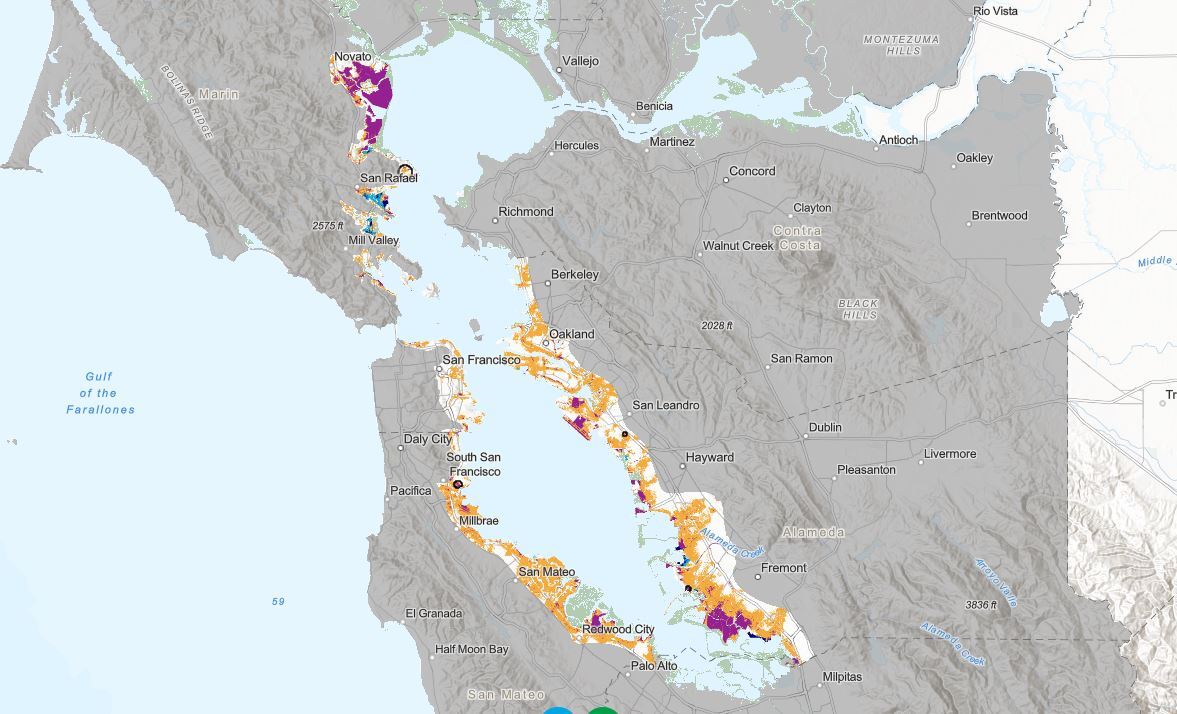

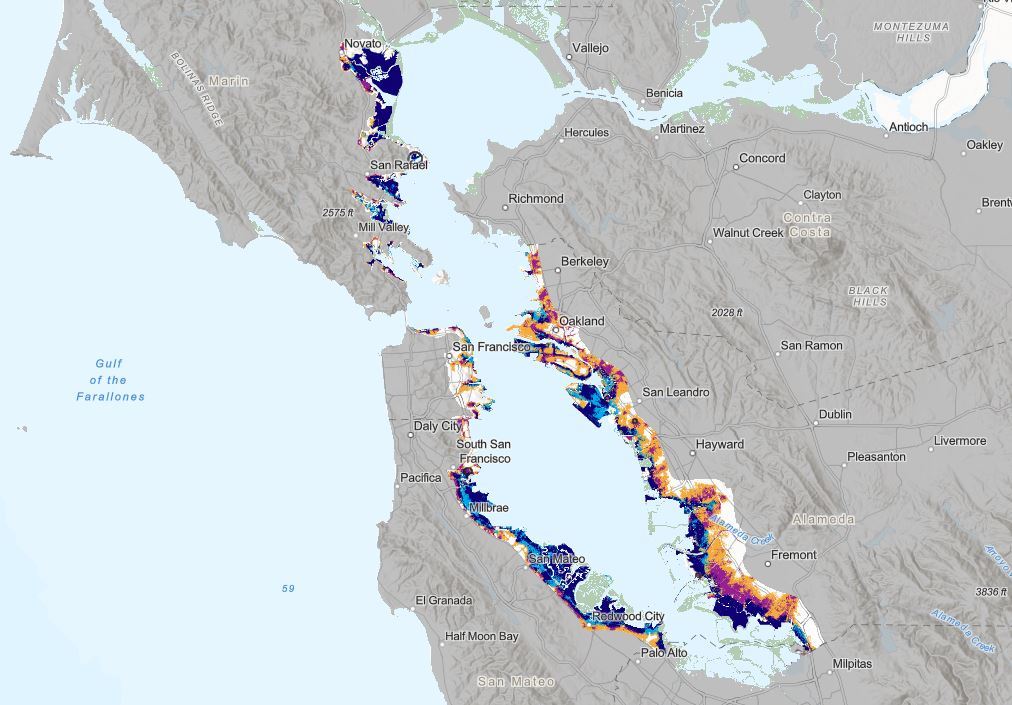

66-inch sea level rise scenario

These initial findings could give water agencies more power to enforce cleanup, said Lisa Horowitz McCann, assistant director of the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board.

“It gives us strong evidence to start making requirements where we have another layer of science that supports that there’s a risk,” she said.

The board recently made a pivotal move in revising regulations by requiring bayfront landfills to pinpoint methods for protecting landfills from rising groundwater in their long-term flood protection plans.

While previous studies have looked at groundwater rise in the Bay Area, this new vetted data set provides the information decision-makers need to understand how to adapt planning decisions for groundwater rise.

Sandra Hamlat, principal resilience analyst in San Francisco’s Office of Resilience and Capital Planning, said the city has “photographic evidence of where there’s already emerging groundwater.”

“I think it’ll make us build smarter,” she said. “We want to make sure that we’re protecting our assets, and I am sure property owners do, too.”

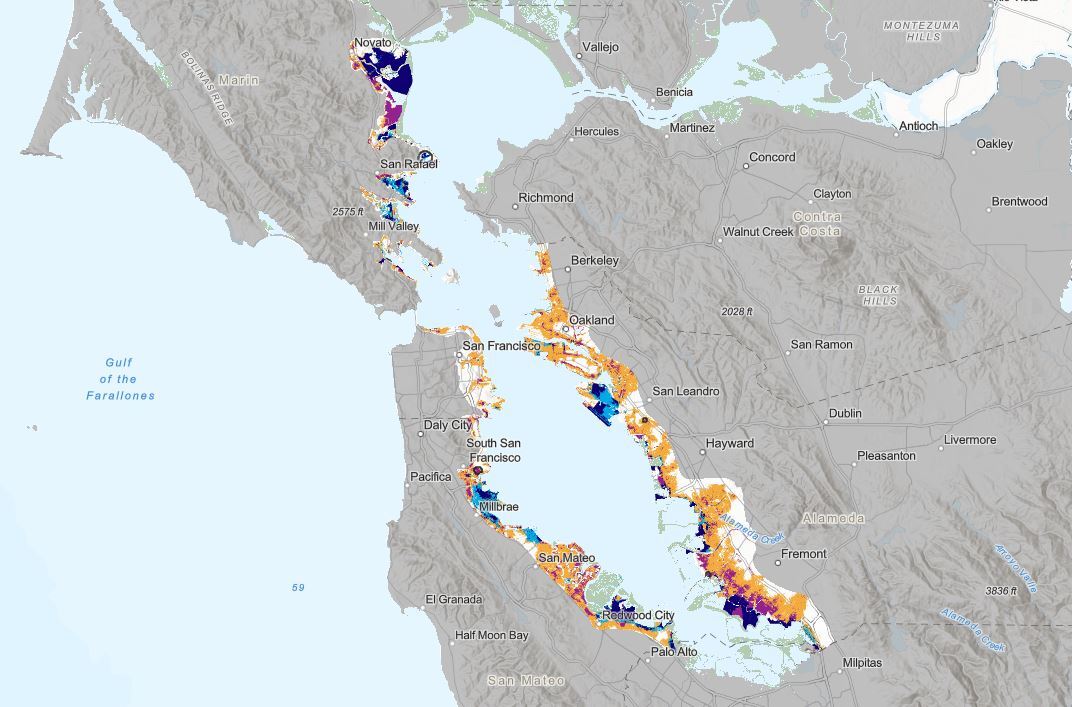

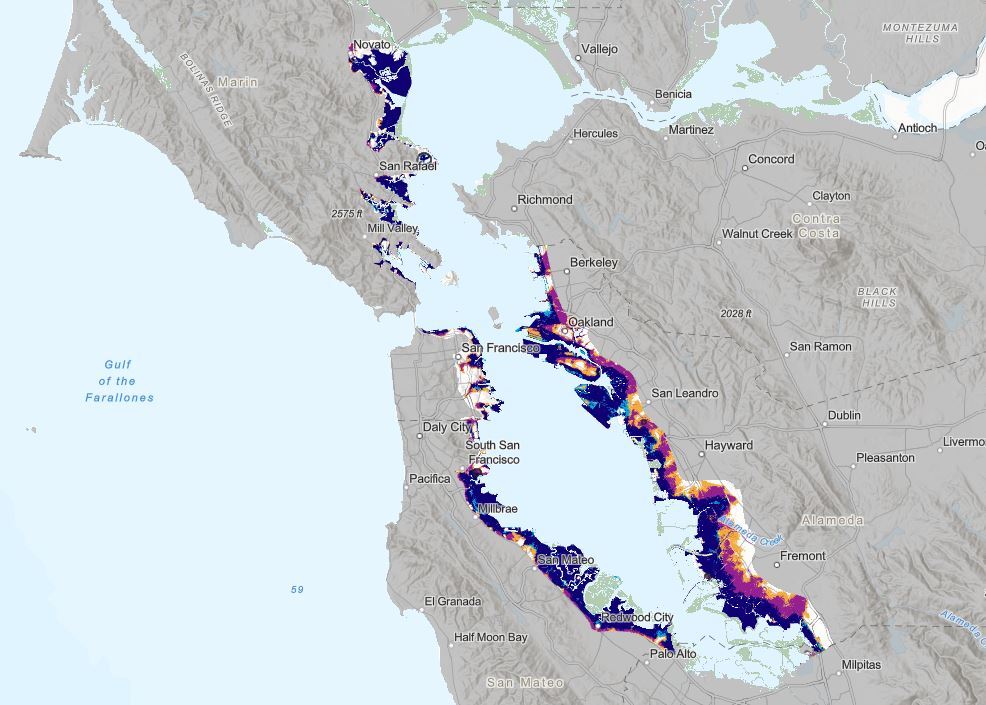

108-inch sea level rise scenario

San Francisco is already using the study’s findings for capital improvement projects. Hamlat said the new data would likely inform which projects are approved and how to modify stormwater and sewage systems to accommodate an immense amount of water.

The findings also suggest that sea level rise projects, like seawalls or levees, may not be enough to keep water out of shoreline communities. That’s a big deal for San Mateo County, where many of these projects are located, said Len Materman, CEO of OneShoreline.

“Wherever those levees are sitting, at the end of the day, they’re going to be along the shoreline area and impacted by groundwater,” he said.

Many San Mateo County cities already see flooding in storms and during king tides, so, he said, emerging groundwater would only add to the issue.

“This is like Miami stuff that we’re seeing in some of our communities,” he said.