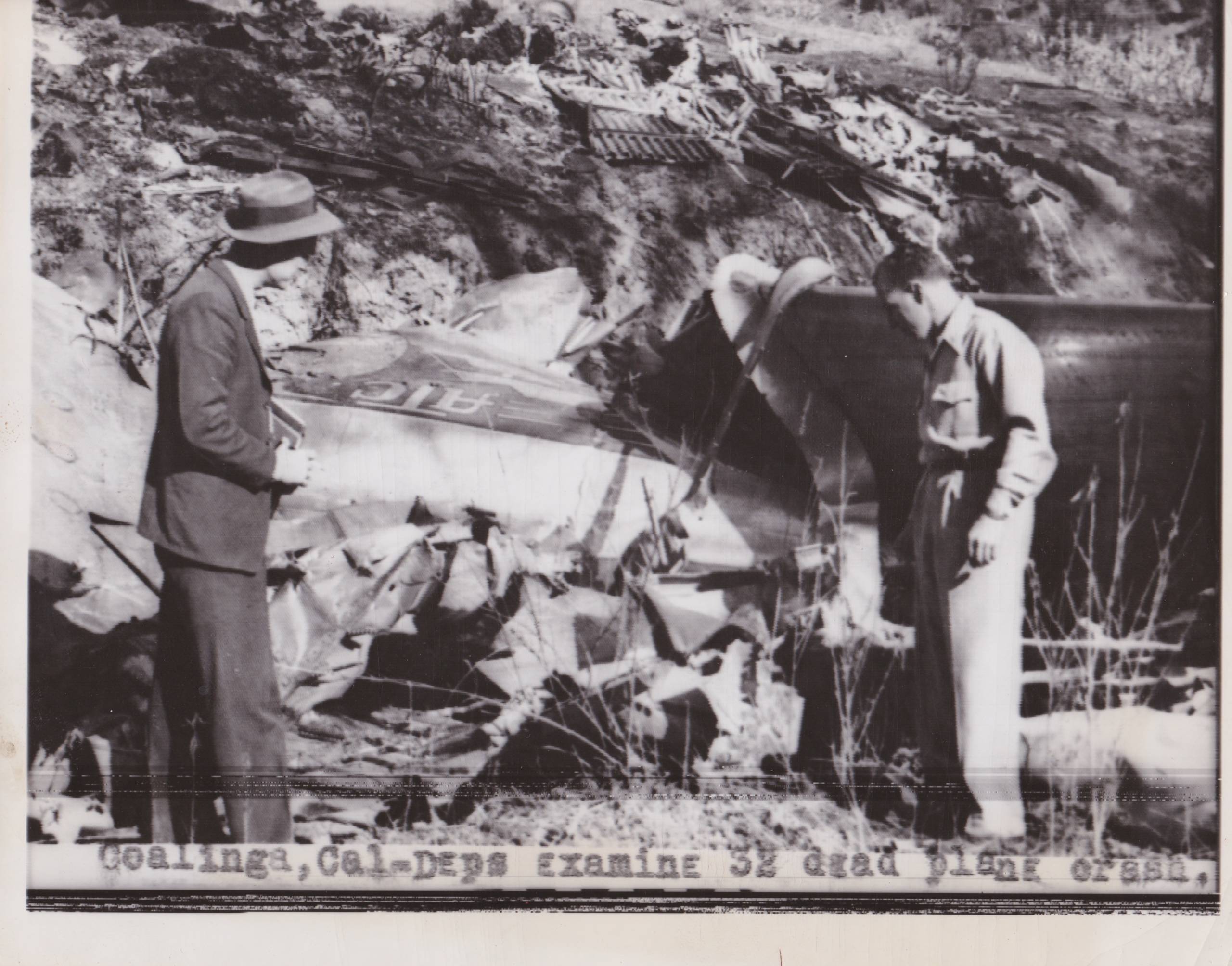

This year marks the 75th anniversary of one of the worst plane crashes in California history. A flight heading from Oakland to the Mexican border on Jan. 28, 1948 crashed into a canyon near the Central Valley town of Coalinga, killing the 32 people on board.

The passengers were 28 Mexican braceros — workers brought to the U.S. through a World War II labor program. Many of their work contracts had ended, and U.S. immigration officials were in the process of deporting them back to Mexico.

The bodies of the white pilot, flight attendants and immigration agent on board were sent home to their loved ones. But the remains of the Mexican passengers were buried in a mass grave in Fresno.

The initial newspaper reports mentioned the names of the white crew members, but only referred to the Mexican passengers as “deportees.” That lack of recognition moved Woody Guthrie to write a song called “Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos)” that has become a folk anthem, sung by artists including Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Bruce Springsteen, Joni Mitchell, Sweet Honey in the Rock, and more. And the band Outernational recorded a version of the song in 2012, as a commentary on modern-day anti-immigrant sentiment.

The Mexican passengers remained unnamed, memorialized only in the song, until author and American Book Award-winning poet Tim Z. Hernandez started investigating who they were, as part of an effort to restore the dignity of their names and stories.

“Those lyrics: ‘Who are these friends all scattered like dry leaves? The radio says they are just deportees,’” Hernandez said. “That song hung in the air for 60 years, until the son and the grandson of migrant farmworkers, born and raised here in the San Joaquin Valley, decided, I wanted to answer that question: ‘Who are these friends?’”

Hernandez has spent the last 13 years traveling across California and Mexico, collecting fragments of what happened on that fateful day, and the stories of the people who were killed. Seven of the passengers’ stories are featured in Hernandez’s 2017 book, All They Will Call You.

Since then, he’s located the families of six more passengers, for a forthcoming sequel. He’s also woven his research into a series of spoken-word and musical performances to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the crash, including a recent appearance in Coalinga, at a museum which still houses the propeller of the plane.

Here are some of the passengers’ stories:

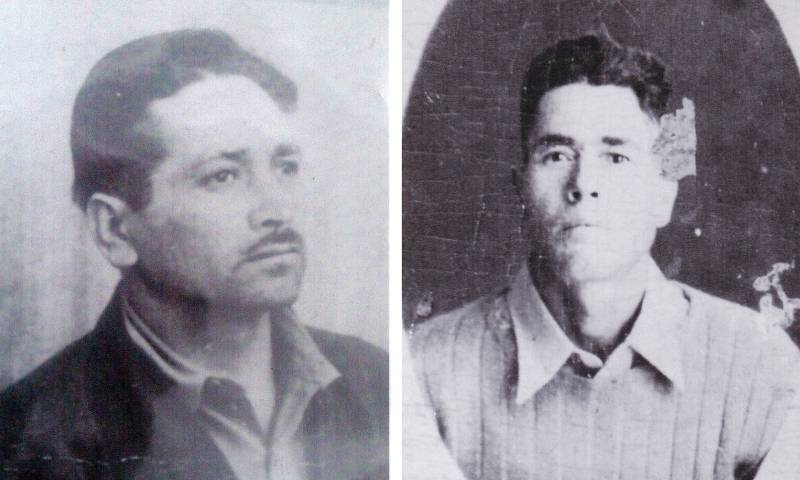

Guadalupe Ramírez Lara and Ramón Paredes Gonzalez: Charco de Pantoja, Guanajuato

When Jaime Ramírez was a little boy, he’d ask his grandmother where his grandfather was and why he’d never met him. She told him that he had died years before. But Ramirez never saw a grave for him at the cemetery in their tiny village of Charco de Pantoja, in the Mexican state of Guanajuato. “My grandmother Elisea just told me that he died in the U.S., in a plane crash,” Ramírez said in Spanish. “That’s all we knew. People talked about this crash where the plane caught on fire and people died jumping out to try to escape the flames.”

When Ramírez later came to the U.S. at the age of 19, his grandmother asked him and his brother Guillermo to try and track down what happened to their grandfather and uncle. Ramírez, who was living in Salinas, traveled to Fresno, where he suspected his grandfather and uncle were buried. He visited the county’s hall of records, and found their names on a list of people who had died in 1948. But at Fresno’s Holy Cross Cemetery, he only found a mass grave, and a caretaker told him hardly anyone came to visit.

Ramírez later moved to Fresno, where he opened a successful Mexican restaurant. He began to research his family history, and the plane crash that forever changed it. He was the first to respond to a notice that Hernandez put in the local Spanish-language newspaper, Vida en el Valle, seeking information from relatives of the braceros who died in the crash. When Hernandez visited the restaurant, Ramírez shared photos, birth certificates, and documents, and handed him a major clue: an onion-skin-thin sheet of newspaper from 1948 that someone from Fresno had sent his grandmother, listing the names, last known addresses and kin of all 28 passengers.

“As fate would have it, this is the first family I would find,” said Hernandez. “[Ramírez] had been doing the research on it for his family and keeping the records of his family for all these years. And I said, ‘What would make you think to keep that newspaper for so long?’ And he said, ‘I’ve been waiting for you.’”

The Ramírez family helped launch Hernandez’s search, and led him to other families. Jaime Ramírez’s brother, Guillermo, accompanied Hernandez on his first research trip to Central Mexico to find and interview more relatives of the passengers.

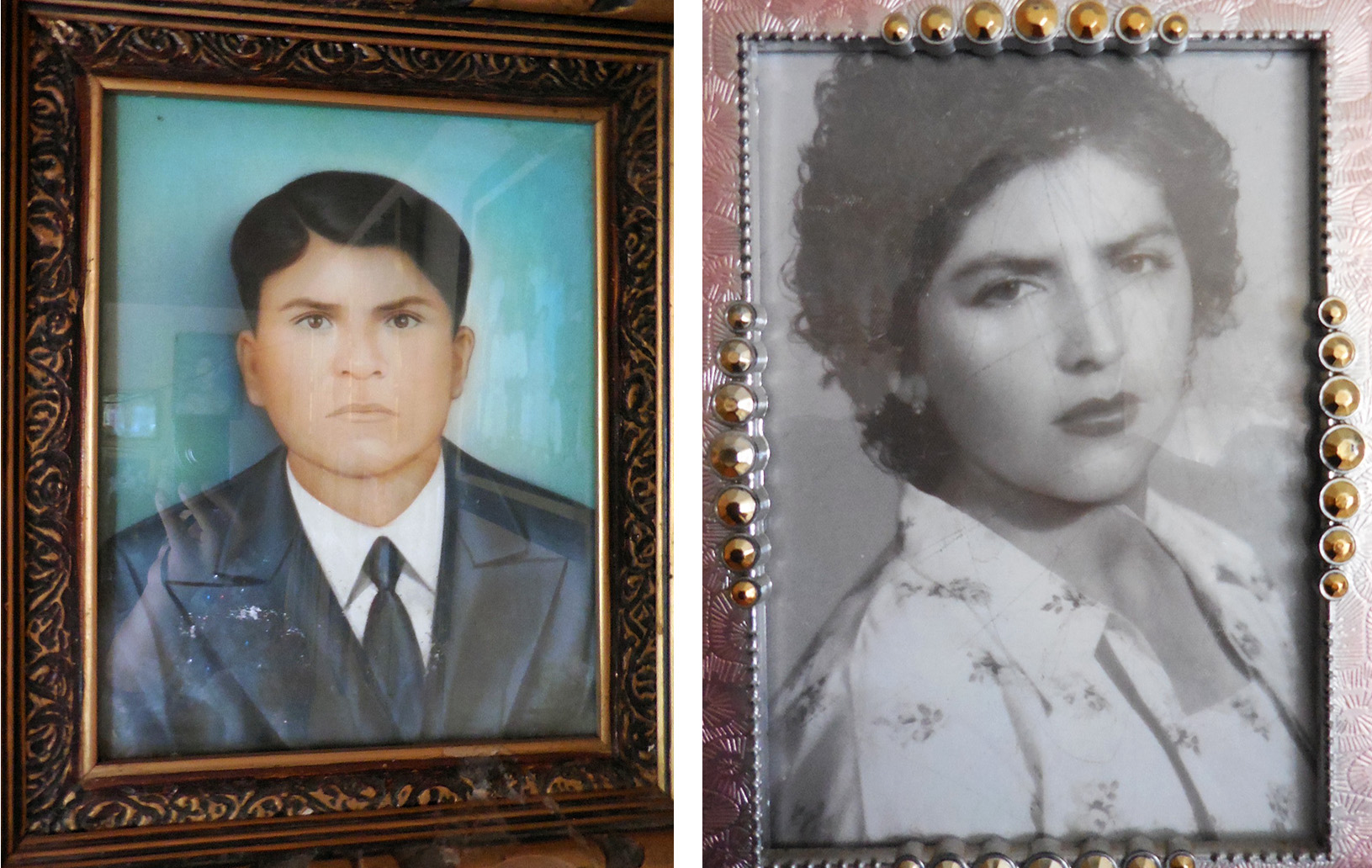

Luis Miranda Cuevas: Jotopec, Jalisco

When he shares the stories in his book, Hernandez often talks about Luis Miranda Cuevas, an adventurous young man who would do anything for love. At least that’s how his fiancée remembered him.

Hernandez went looking for traces of Luis Miranda Cuevas in Jotopec in the Mexican state of Jalisco. He asked everyone he met in the tiny town — municipal officials, the librarian, a school principal — for any information about surviving members of Miranda Cuevas’ family. Most told him that everyone old enough to know him would have passed away.

But eventually, a man came forward to say that his aunt, Casimira Navarro Lopez, was once engaged to marry Miranda Cuevas. By the time Hernandez finally found her, in 2015, she was in her 80s.

“And as a writer, searching for the story, you want somebody to be named Casimira in this story,” said Hernandez. “The translation of Casimira is ‘almost sees.’ Isn’t that how all of our memory works? Like, we kind of almost see it, but we don’t quite sometimes.”

She told Hernandez that Miranda Cuevas would do anything to be with her — even when her father forbade their courtship. He would sometimes even dress up as a woman so he could sneak into their house and sew and embroider with her, Navarro Lopez said.

She said she had spoken to her fiancé the day before he died, when he called her from a detention center in San Francisco.