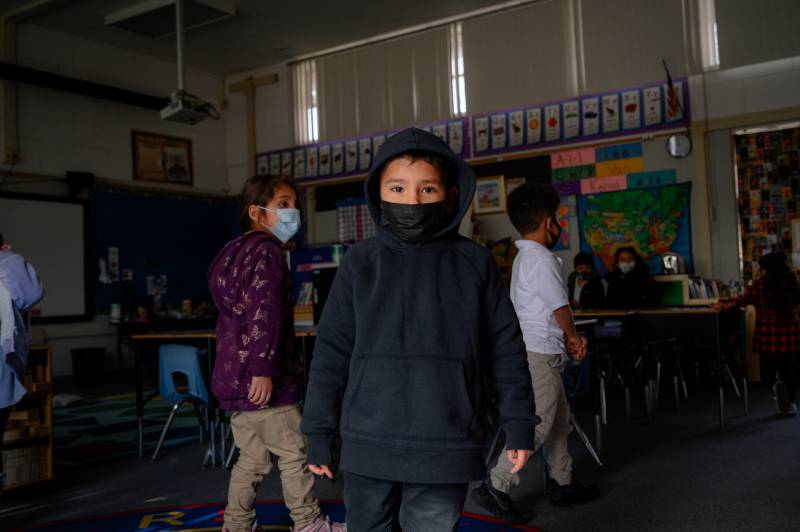

Jaime Pacheco, 5, has spent half of his life in a pandemic.

He was still learning to talk when the lockdown began. That was also when his mom gave birth to his sister. COVID-19 hit his working-class and immigrant community in East San José hard, and his family stayed at home to protect the baby and everyone else from getting sick. When they did go on an outing, his mom, Itzia Morfin, said she kept her kids far away from people.

So when he stepped into a classroom for the first time last fall, Jaime had a hard time pronouncing words and expressing his feelings, and threw a tantrum unlike any Morfin had seen before.

“It was all new to him. He didn’t know how to act around other kids, around the teacher,” she said.

Jaime is among tens of thousands of children who began their schooling this year when California made transitional kindergarten, or TK, more available as part of an ambitious plan to create the nation’s largest universal preschool program in the next three years.

Transitional kindergarten is intended to better prepare 4- to 5-year-olds for kindergarten. The new grade is not mandatory, but gives parents the option of getting their children into schools sooner, which can help reduce child care costs that have become increasingly unaffordable and unavailable.

But this first year of implementing the expansion has been bumpy. Some school districts didn’t meet enrollment expectations, and some saw a jump in enrollment, although that meant taking away kids that were in preschools and destabilizing child care businesses.

One of the biggest challenges has been staffing. The majority of districts reported they didn’t have enough qualified teachers or child care staff to cover beyond the half day of classroom time.

Last month Gov. Gavin Newsom proposed to increase spending on the $3 billion initiative, despite a projected $24 billion deficit for the 2023–24 budget year, so that the state can continue ramping up the program.

“We’re not by any stretch of the imagination where we need to be, but we’re not backing off in terms of accelerating these priorities in terms of our efforts to transform our public education system,” Newsom said when he unveiled his budget plan in January.

The state is giving school districts time to fully implement the program by phasing in younger students each year. Currently, students who turn 5 between September and February 2 are eligible for transitional kindergarten. Next fall, tens of thousands of children who turn 5 between September and April 2 will be qualified to attend class.

By the 2025–26 school year, all children who turn 4 by September 1 can sign up for TK.

While the California Department of Education hasn’t released this school year’s attendance data for TK, it appears enrollment didn’t grow as much as the state anticipated. Newsom’s budget proposal lowered spending estimates for the first year of the expansion, and the governor taped a video last month to encourage families to enroll age-eligible kids and “start their schooling on the right track.”

Newsom also postponed plans to reduce class size from 12 students for every teacher to 10 students per teacher, and held back funding to renovate or build the appropriate facilities for TK-age children.

But one Bay Area school district is having more success. Over the last two years, TK enrollment in East San José went up from 262 to 324.

That’s because the Alum Rock Union School District has been gradually growing its TK program since 2015. It skipped ahead of the state’s expansion schedule by phasing in 4-year-olds earlier; it’s keeping classroom size small, at just 20 kids per two adults in the room so the students get the attention they need; and it’s offering after-school care to meet the needs of working parents.

The district also partnered with Kidango, a nonprofit child care provider, to convert an elementary school into an early learning center where babies up to kindergarten-age kids will receive a full day of care — all on one campus.

“The idea of repurposing this facility came from listening to people in the community who said ‘we need something that is local, something where we don’t have to go driving far away,’” said Dianna Ballesteros, director of early learning for Alum Rock Union.

Declining elementary school enrollment prompted district officials to move older students to other campuses while the TK and kindergarten students stayed put, she said.

Now those empty classrooms are turning into a day care: Desks, chairs and whiteboards are being replaced with short sinks, tables and cubbies for smaller kids and cribs and diaper-changing tables to welcome infants and toddlers by the next school year.