Online handwashing tutorials. Hand sanitizer hoarding. And in every public bathroom, signage urging you to wash your hands to slow the spread of the coronavirus.

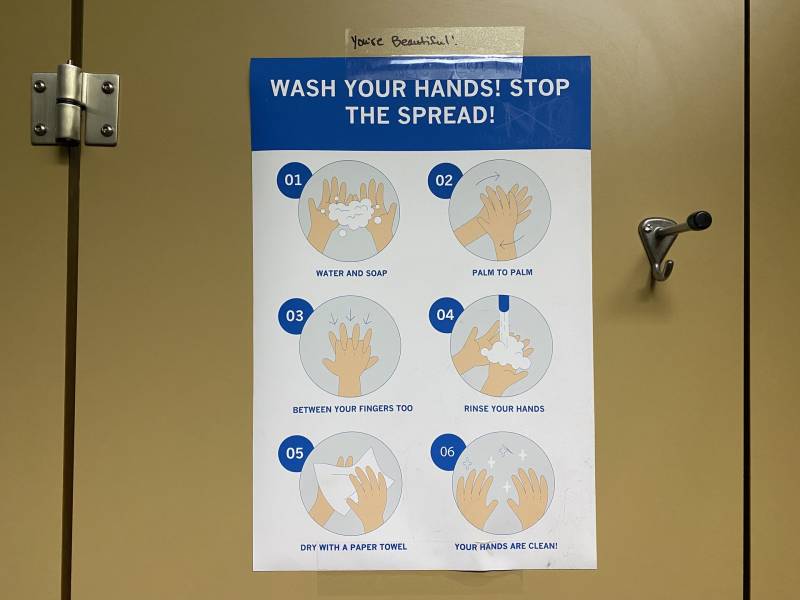

It may be hard to believe now — after over three years of passionate conversations about masking — but when the COVID pandemic first hit in 2020, vigilant hand hygiene was positioned alongside social distancing as a key measure in the fight to slow the spread of SARS-CoV-2 around the country. And while it’s true that conversations about hand hygiene haven’t entirely vanished — just look at the laminated 2020-era handwashing posters you’ll still see in many public bathrooms around the Bay Area — “wash your hands” has undoubtedly receded as a core public health message at this point in the pandemic, in favor of masking, vaccination and booster shots.

But as we continue into Year Four of the COVID pandemic, should handwashing be something we keep in mind for our daily health?

The short answer is: absolutely — but it’s no longer really about COVID. Keep reading for the science behind those 2020 recommendations, the kinds of illnesses that handwashing can help protect you against and how useful hand sanitizer really is.

Why was handwashing such a big thing when the pandemic first hit?

To understand why hand hygiene was so emphasized in the first weeks of the pandemic, it’s crucial to understand just how little was initially known about the coronavirus, says Dr. John Swartzberg, clinical professor emeritus of the Infectious Diseases and Vaccinology division at UC Berkeley.

“In March of 2020, we didn’t really know much about how this brand-new virus was transmitted,” said Swartzberg. “And we assumed that it was transmitted like other respiratory viruses, probably just by droplets, maybe by air, but probably just droplets.”

In the absence of initial research, the medical community “said the basic things about transmission of respiratory viruses,” said Swartzberg. “Many of them were transmitted by inanimate objects, what we call fomites. And so, therefore, handwashing would be very important.”

“We didn’t know that in terms of any science to support that. Just like we didn’t know that SARS-CoV-2 is primarily transmitted as an airborne virus, but also can be droplets,” said Swartzberg.

Another reason handwashing was so initially emphasized, says Swartzberg, was based on the earliest research on the coronavirus and fomites — that is, those surfaces and objects that could carry the virus.