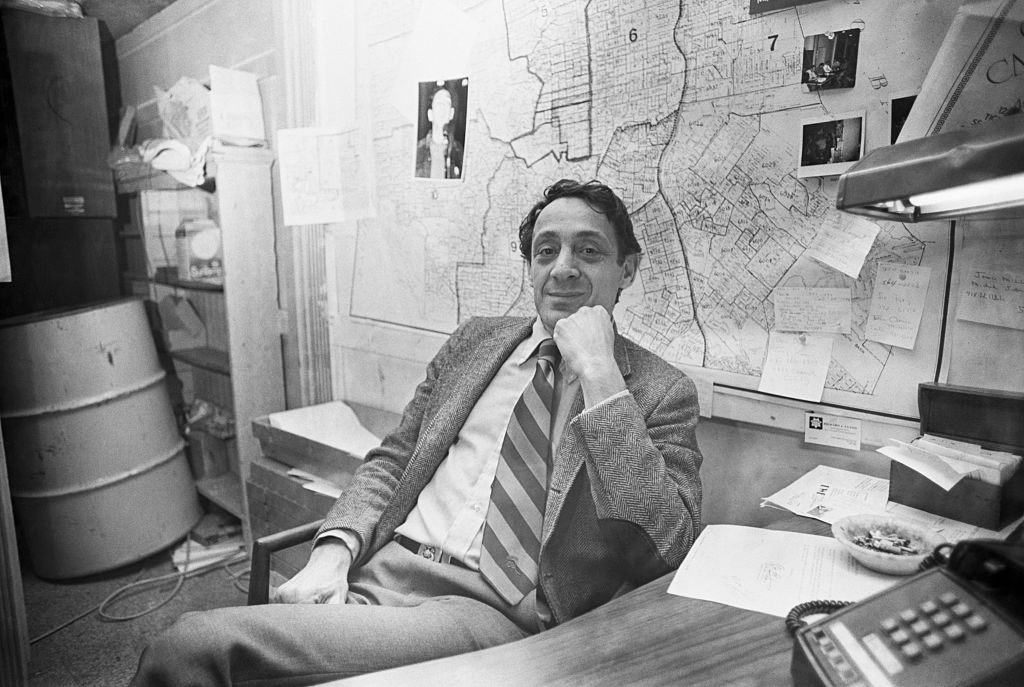

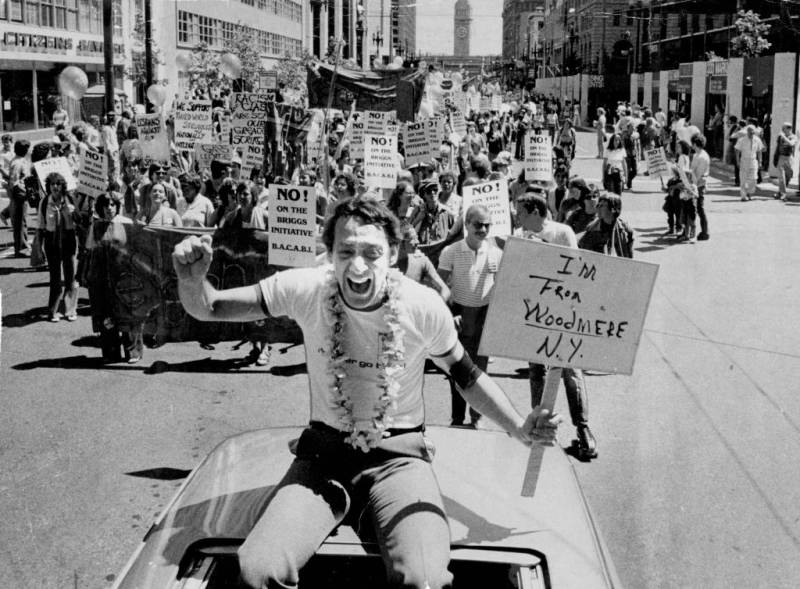

Beginning in 1977, for nearly a year, Harvey Milk served on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors — the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in California. He authored a bill banning discrimination in public places, housing and employment based on sexual orientation. He also promoted free public transportation, cheaper child care facilities and public oversight of the police.

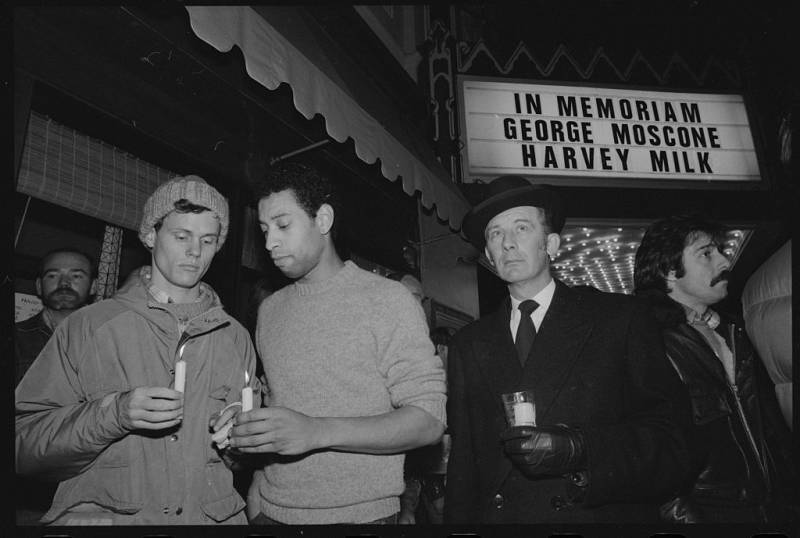

In November of 1978, Milk and San Francisco Mayor George Moscone were assassinated. The city mourned the loss of two of its most outspoken political leaders. Over the years, Harvey Milk became a martyr for causes of equality and social justice, and in 2009, the state of California designated May 22, Milk’s birthday, as Harvey Milk Day.

At a time when LGBTQ+ rights are under attack nationwide, with a string of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation introduced in dozens of state legislatures, the significance of Harvey Milk as a politician and activist resonates more than ever.

Cleve Jones, author and longtime activist, talked to KQED’s Brian Watt about Milk as a person, a politician and an icon.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Brian Watt: Can you take us back to when you met Harvey Milk? What was that like?

Cleve Jones: Well, Harvey was quite a character. When I first met him, he was still emerging from his hippie phase, and he struck me as being entirely too old to be wearing a ponytail. But he and his partner, Scott Smith, had opened a little camera store on Castro Street, and I met him on Castro Street as he was registering voters. And that was our first conversation. I was struck by his warmth, though, and he ran for office a few times before he was elected.

And with each campaign, I could see that he became more serious, more grounded in the issues and more thoughtful in his approach, which was never a single-issue thing. He cared, of course, about gay rights, the community we now call LGBTQ+. But he cared about unions, he cared about seniors, he cared about kids. He was a very astute coalition builder.

What are some of the things he taught you about coalition building and government and advocacy?