O

n another day, Matt Juanes would have set out on the water long before sunrise.

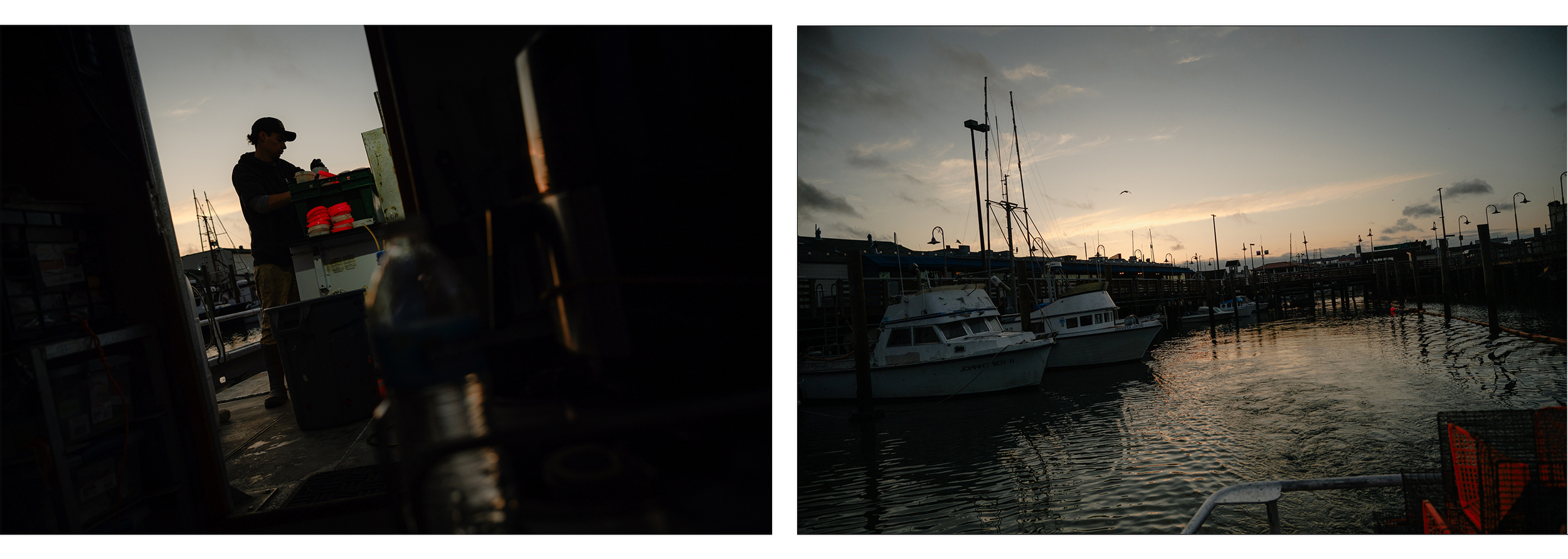

But this still June morning, Juanes was taking his time. As dawn flickered across the sky, the San Francisco-based commercial fisher and his deckhand carefully checked their ropes and bait jars and the dozens of fishing pots piled at the back of Juanes’ boat. Juanes was hoping to get ahead of any issues they might encounter out at sea. Still, he was almost certain something would go wrong.

Juanes, an experienced salmon and crab fisher who has worked out of Fisherman’s Wharf for over five years, is no stranger to the trade. Today, though, he would be chasing an unfamiliar catch for the first time: coonstripe shrimp.

“This is all new to me,” Juanes, 46, said. “This is going to be a learning experience.”

Juanes is one of hundreds of commercial fishers who dock along the Golden State coast and who would normally be out hunting mighty chinook or “king” salmon — the mainstay of California’s commercial salmon fishing industry. The first months of summer are typically a premier time for both salmon and salmon fishers.

But this summer, California’s salmon fishing season is completely shut down for the first time in over a decade. Last year, only 62,000 adult fall chinook salmon returned to the rivers of the Sacramento Valley to spawn — the third-worst year on record, according to the state Department of Fish and Wildlife. In April, the Pacific Fishery Management Council issued its response: Salmon fishing all along the California coast would be shut down (PDF) this year.

The decision, which fishery managers hope will give salmon time to recover, has left California’s commercial fishers scrambling to find alternate sources of income.

“There’s a lot of fear and panic all up and down the coast,” said John McManus, senior policy director of the Golden State Salmon Association, at a press conference in April. “People are wondering how they’re gonna pay the bills this year.”

The Biden administration is considering whether to declare a federal resource disaster, which would allow Congress to provide financial assistance to people affected by the closure. A disaster declaration came swiftly during the last salmon fishing closures in 2008 and 2009, and political leaders, including Gov. Gavin Newsom and U.S. Rep. Nancy Pelosi, have called on the federal government to act quickly again.

But as summer arrives, fishers are still waiting for news.

Back at Fisherman’s Wharf on that early June morning, Juanes and his deckhand, Angelo Rovetta, were making the final preparations to Juanes’ boat, the FV Plumeria, to set out.

Salmon account for close to two-thirds of his income every year, Juanes says, meaning a federal relief check would make a big difference. Shrimping could bring in some cash, he said, but it wouldn’t be anywhere near enough to make up the loss.

“Nothing’s going to replace salmon,” he said. “It’s going to be a real tough struggle this year.”

He and Rovetta undid the moorings, and headed for the open ocean.

The salmon, the fishers and the crash

Biologists have estimated that before the Gold Rush, more than 1 million fall chinook would come back to the Central Valley to spawn — a stark contrast to the 62,000 that arrived last fall.

The decline is largely the result of nearly two centuries of environmental degradation the Central Valley’s rivers and tributaries have suffered since the Gold Rush, first through the effects of intensive gold mining, then thanks to generations of dam and levee building and massive water diversions to serve the state’s farms and cities. Introduction of non-native predators and fishing pressure have also played a part.

The dams cut off most chinook from their cold-water spawning grounds in the upper reaches of Central Valley tributaries and streams. To try to mitigate the damage, state and federal authorities built hatcheries up and down the valley. But now, the effects of climate change — limiting the supply of cold water during drought years and playing havoc with salmon’s food supply in the Pacific Ocean — appear to be accelerating the fish’s decline. The fall chinook population has plunged to record lows twice over the last two decades.

Although salmon numbers tend to rise and fall every few years, researchers say the fall chinook have become increasingly volatile.

“We are not in a great phase,” said Rachael Ryan, a doctoral candidate studying salmon life histories at UC Berkeley. “It’s just going to get worse — the unpredictability.”

Fishery disaster declarations, explained

When disaster hits one of the country’s regional fishing areas, or fisheries, the federal government can use a disaster declaration to send aid checks directly to the fishing communities affected.

Last year, the Commerce Department did just that after several crab and salmon fisheries failed in Alaska and Washington state. The decision led to $220 million in aid for the fishers, businesses and communities those disasters affected.

The federal government also declared a disaster when critically low numbers of chinook salmon led fishery managers to shut down fishing off the California coast in 2008 and 2009.

How a declaration works

The first step in the disaster declaration process is a request for aid, often from a state governor. Then, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) looks at the situation and reviews that request.

Next, the secretary of commerce makes the final decision on whether to declare a disaster. The declaration moves to Congress, which decides how many federal dollars to set aside for relief aid. Finally, NOAA distributes the funds to fishers.

How quickly did it happen last time?

When California’s last salmon closure happened, the disaster process moved fast. In March 2008, the governors of California, Oregon and Washington signed a letter asking for a federal disaster declaration. Secretary of Commerce Carlos Gutierrez issued the declaration May 1. In July, Congress approved $170 million in relief. By September, payments had started making their way to salmon fishers along the West Coast.

Where are we right now?

The process is moving more slowly this year. Newsom formally requested a disaster declaration on April 6, but it’s still unclear when or whether the Commerce Department will act. A NOAA spokesperson told KQED that the agency is still reviewing the situation.

“We are evaluating the current requests as promptly as we can,” NOAA Public Affairs Officer Michael Milstein wrote in an email. “But at this point we cannot predict a specific timeline” for referring the requests to Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo.

Northern California’s Yurok Tribe and the governor of Oregon also have requested similar declarations for their salmon fisheries.

If Raimondo does declare a fishery disaster in California, some experts say Congress is likely to respond promptly. Lawmakers have already set aside $300 million for fishery disaster aid as part of the 2023 fiscal year appropriations bill.

“This is exactly the kind of problem that Congress especially loves to respond to,” said UC Santa Barbara Professor Sarah Anderson, who studies how governments react to environmental disasters. “It’s likely to lead to some relief for those who are affected by the closure.”

“We are pretty good at thinking quickly in an emergency,” San Francisco-based commercial fisher Sarah Bates told reporters during a press conference in April. “Things happen at sea. But this one is bigger than that — we need help.”

A long year ahead

Whether aid comes or not, this year will be a long one for many salmon fishers. Some, like Juanes, are making sharp pivots to new kinds of catch that they have little experience with. Others are turning to land jobs.

All are once again confronting the murky future of California’s chinook salmon and the state’s commercial fishing sector — an industry that has shrunk from thousands of boats in the 1980s to fewer than 500 today.

Juanes suspects fishery managers will want to give salmon more time to recover and cancel next year’s fishing season, too.

As they turned out along the coastline toward his planned shrimping grounds, Juanes leaned on the helm and recalled his decision to start fishing full time.

Juanes himself was not a commercial fisher during the chaos of the last salmon closures in 2008 and 2009. He was at work repairing high-end ovens and stoves across Northern California. It was a stressful job, full of hours of traffic and frustrated clients.

“I drove all over the place and kind of burnt myself out,” he said. “I just never felt really happy.”

In his spare time, Juanes would drive to the coast from his home in Santa Clara, take a small boat with an outboard motor out on the water and go fishing for halibut and rockfish. He didn’t completely know what he was doing, but he knew that it felt a lot better than his appliance work. In 2017, Juanes made the decision to leave his job to start fishing commercially.

Looking back, Juanes wishes he had taken more time to learn about the industry before taking that leap. He wasn’t prepared for how demanding the work was and didn’t know that the industry was facing turbulent conditions. That year, the number of chinook salmon returning to the rivers had plunged again.

But Juanes says he has no regrets. Immediately, he remembers, he felt some of the stress lift from his shoulders.

“I don’t say it was the smartest thing to do,” he said. “But it was something that I did.”

Out on the water, Juanes slowed the Plumeria to a crawl. The ocean was calm and still. In the distance, the towers of the Golden Gate Bridge rose against a gray sky.

Juanes and Rovetta hauled their shrimp gear up against the railing and readied a long length of rope and a set of buoys. Rovetta rearranged a stack of shrimp pots so they were ready to drop into the water.

“Kind of scary, setting all this up and then knowing you’re just throwing it out in the ocean,” Juanes said.

He laughed. “Hopefully it comes back to me,” he said.