When Joe Sanchez was 8 years old, his grandmother asked him to make a promise to never forget his California Indian heritage.

She was determined to see the culture live on, after watching her brothers deny their Coast Miwok ancestry, a matter of economic survival in early 20th century California.

Today, at 75, Sanchez is making good on that promise in a more ambitious way than he ever imagined: He’s bought back a piece of his ancestral homeland. In July, he and the Coast Miwok Tribal Council of Marin purchased a 26-acre piece of land in the rural Marin County community of Nicasio, once Coast Miwok territory.

“We needed a place to have ceremony, a place where we could do all those things that we always did for thousands of years,” he said.

It’s believed to be the first modern “Land Back” effort in Marin County, part of a growing movement across California to get land back to the original indigenous people who lived on it. At least a dozen Land Back endeavors have already succeeded, from an island returned to the Wiyot tribe in Humboldt County to the Esselen tribe’s purchase of a 1,200-acre ranch near Big Sur.

‘We’re home’

On a sunny afternoon recently, Sanchez stood in the shade of an oak on the land in Nicasio, which is nestled in rolling hills and covered in tall grasses and brush. He said the tribal council imagines a place where they can bring together people with Coast Miwok roots from around the region.

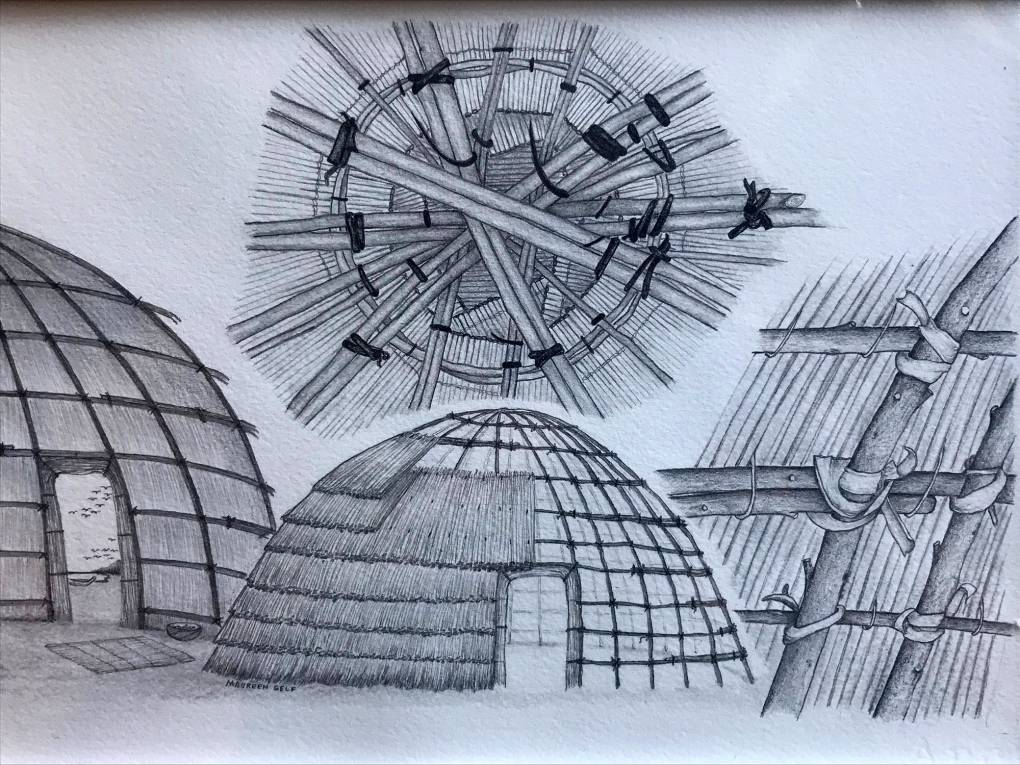

At the foot of a hill that encompasses much of the property, he pointed out a flat area where they plan to build a dance arbor, a roundhouse and a sweat lodge — places to dance and sing and sit in ceremony without having to ask anyone’s permission.

Sanchez was joined by Dean Hoaglin, a founding member of the tribal council. “It’s beautiful to be on our land,” Hoaglin said. “We’re home.”

After he and Sanchez helped form the council, Hoaglin said an elder told him the ancestors were calling him to the land.

“It’s time that we come back together and that we fulfill what our ancestors always prayed for, and that was for us to come back home and to share the original teachings,” Hoaglin said, referring to indigenous values about how to live in harmony with the natural world and each other.

Hoaglin has spent 30 years teaching traditional cultural practices as part of a suicide prevention program for Native American youth in Sonoma County. He’s planning to retire this year. With the extra time, he wants to plant a garden here on their newly returned land, grow traditional foods and medicinal plants, and teach indigenous land stewardship practices.