Few dates hold as much resonance in the history of American rock ’n’ roll as Feb. 3, 1959.

On that day, a single-engine plane with room for only three passengers crashed into a cornfield in Clear Lake, Iowa, just minutes after takeoff. The pilot and three budding stars of rock ’n’ roll — Buddy Holly, J.P. Richardson Jr. aka The Big Bopper, and Ritchie Valens — all died. That winter day became known as “The Day the Music Died,” and was immortalized in the 1971 song “American Pie” by Don McLean.

Valens was the youngest on board at 17 years old. The Mexican-American singer from Pacoima, in the San Fernando Valley, had begun his career less than a year earlier. Yet, his legacy was already cemented through his timeless hits including, “We Belong Together,” “Donna,” and his widely beloved interpretation of the Mexican folk song, “La Bamba.”

In 1987, the film La Bamba starring Lou Diamond Phillips, captured Valens’ life story. Los Lobos, the veteran East Los Angeles rockers, performed Valens’ music. The band’s cover of “La Bamba,” went on to become a No. 1 hit upon the film’s release, reintroducing the music of Ritchie Valens to a new generation of fans.

Almost 40 years later, award-winning poet and San José State professor J. Michael Martinez has created a new, poetic ode to Valens. Tarta Americana, which is Spanish for American Pie, uses the life and music of Valens to better understand issues around race, culture and politics as they show up in Martinez’s own life.

Sasha Khokha’s interview with J. Michael Martinez has been edited for length and clarity — for the full version, listen to the audio at the top of the page.

Sasha Khokha: How did you first get into Ritchie Valens’ music?

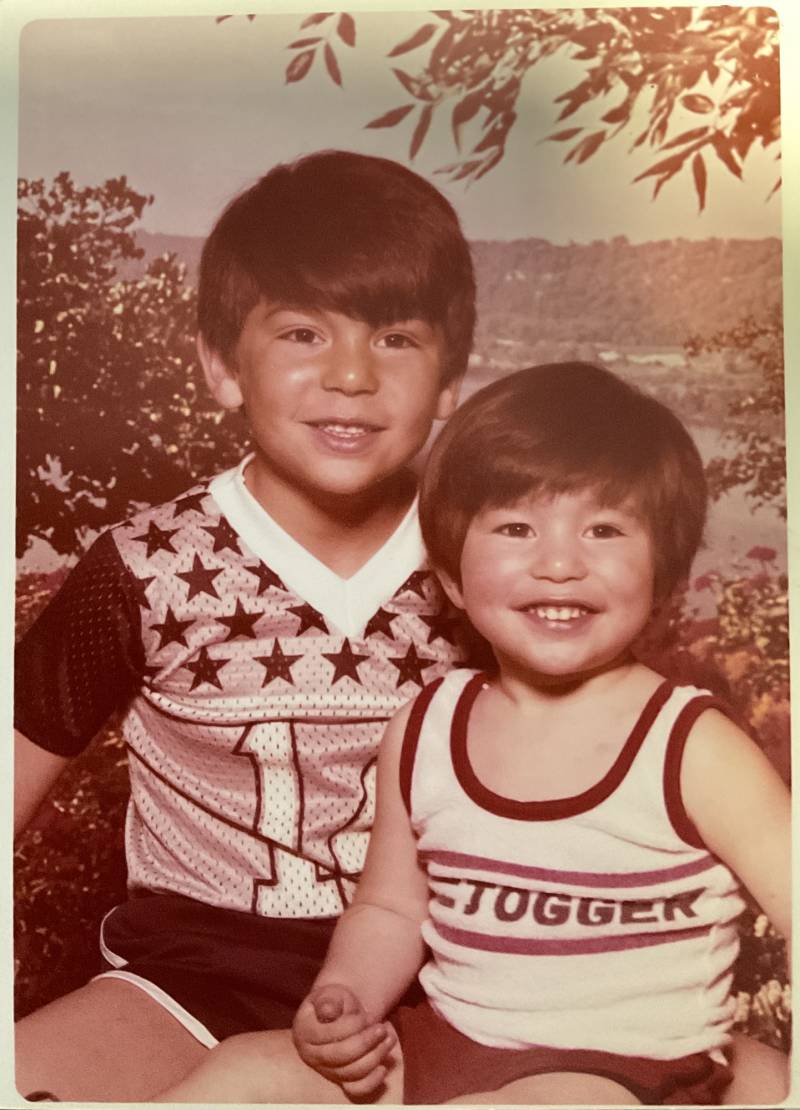

Michael Martinez: My mother had “La Bamba” on vinyl, and it was actually the first record that she owned, so she would throw it on the record player growing up. After the movie came out, I was completely enthralled. And so, we ended up having the soundtrack always going and as a child, I would dance to “La Bamba.”

My mom had such a visceral, joyous response to the sound of his voice and to that opening pluck of guitar. To see my mother immediately joyous and jovial, shaking and ready to dance, that was always a sign that it was going to be a good day.

You mention the film La Bamba a lot in this book. Tell me your first memories of watching it.

I distinctly remember this. We were in our little TV room. We’d ordered pepperoni pizza and my mother pushed it into the VHS and [hit] play. And [there’s] the opening music that the film has and then this particular scene of Latinos and Latinas in the fields harvesting and gathering.

No other film that I’d seen up to that point as a child had ever resonated with me in that way before. Because there were people that looked like my uncles and aunts, that looked like my mother, my father, and then Ritchie who was not able to speak Spanish fluently, like me.

It really changed my perspective of racial identification. Even as a child, I was like, “Oh, here’s a Chicano that can’t speak Spanish fluently like me that is interested in art like me.” He was deeply, deeply important — a pivotal figure for me to comprehend what it means to be a Chicano, a Latino, in the U.S.

Are there parallels that you see in terms of Valens’ journey as an artist and yours?

He was very much a presence in my young childhood, and so radically influenced my visions of what an artist can be. When he was singing, that music was meant to generate community and to generate hope and love, to bring people together, to see them in their joy. That full effort to pursue art, to pursue music, parallels for me the desire to pursue poetry in language and to cultivate community in the hopes of providing some avenue toward joy.